Weekly Wrapup: How are Indian Banks holding up

Before we get to today's main story, a wrapup of all the things that happened this week. On Monday we talked about Baba Ramdev and Patanjali shares. On Tuesday we talked about artificial ripening of fruits. On Wednesday we talked about the Black Sea Grain Initiative. On Thursday we talked about India's post harvest loss problem and finally we talked about the tussle between Spotify and Zee News

And with that out of the way, let's talk about Indian banks

The Story

If you read our story on the Silicon Valley Bank crisis, the first half of this story will sound familiar to you. But since we’re talking about banks, we have to explain some of these concepts. A little refresher never hurt anyone, but, if you want to skip this and get straight into the Indian banking system, just go straight to Part 2.

Part 1: The Model

See, banks have a simple business model.

They take deposits from people like us and pay us a low rate of interest. They then lend most of these deposits out to others and earn a higher rate of interest. The difference between this deposit rate and the lending rate is their margin. And they make a decent chunk of money this way.

But not all of the money gets doled out as loans. They set some aside as cash. Just to be safe in case of a crisis. And the rest of the money is invested in things like government bonds. It’s a relatively safe investment that may not earn them the big bucks but they can sell these bonds quickly in case of an emergency.

But things could go wrong. The folks who borrowed money might default. Or the investments could turn out to be duds and create losses.

When people see this happening, they could panic. They could rush to withdraw their money from the bank to keep it safe. It’s called a bank run. And banks will have no choice but to use the cash they’ve kept aside for emergencies. They might have to sell their bond investments too.

Now depending on the economic environment, this could be a bit of a problem. Because bonds are wired a little differently. The price of a bond and its yield — which is another word for returns — move in opposite directions. The reason is actually simple. Imagine you pay ₹100 and buy a bond. And you get 5% interest or a yield on it.

Now imagine the central bank raises interest rates. They issue new bonds at 7% interest.

Suddenly, the bond that gives you a mere 5% is not attractive anymore. People like you who’ve bought it rush to sell it. You’d rather put money in the new 7% bond.

Now you know that when people sell, the price takes a knock. And let’s say that the price of the bond falls to ₹98. Suddenly, investors realize that the bond is available at a discount of 2%. So if they buy it now, they’ll benefit from the discount and also get the 5% promised interest.

Basically, as the price falls, the overall yield rises. And vice versa.

And in an environment like today when central banks are busy raising interest rates to curb inflation, it has a negative impact on all the bond investments made by banks.

Part 2: How are Indian banks placed

Now that the primer is over, let’s focus our attention on Indian banks.

So the first thing to address is a bank run. It’s something that happened at Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse. But also, you must know that such events don’t happen every day. Rather, there was something that made these banks especially vulnerable — the kind of clients they catered to.

You see, SVB had raised a lot of deposits from startups. And Credit Suisse had a lot of ‘extremely rich clients’ as Bloomberg put it. Both of these segments are quick to follow the herd. If they see their peers pulling out money, they’ll rush to do the same thing. Money will flow out quickly. And that puts pressure on the bank.

But if you look at how most Indian banks raise money, it’s from households. Over 60% of the deposits are from people like you and me. These deposits are typically what you’d call ‘sticky’ money. It’s not as prone to flights of despair. Sure, households will still panic. But the probability of this happening is less according to the experts. Or as a paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives put it, “bankers have been heard to joke that a depositor is more likely to get divorced than to switch banks.”

Okay. So the deposits seem fine. What about the investments? Aren’t rising interest rates bad for Indian banks?

Not exactly. In fact, it’s quite a good thing initially.

Yes, we know this sounds a bit confusing since all this while we spoke about how the bonds that banks invest in suffer from losses when interest rates rise, right?

And that part is still true. But there are a couple of nuances here.

Firstly, you need to understand how the bonds themselves are split in Indian banks. Typically, only around 20–30% of the deposits that banks raise are set aside for these types of investments. And these bond investments show up in 3 ways in a bank’s books.

- Held For Trading (HFT)

- Available For Sale (AFS)

- Held to Maturity (HTM)

The labels are quite self-explanatory, no?

Let’s look at HFT and AFS first. Now if a bank has invested in bonds for the purpose of trying to bet on interest rate movements and make a quick buck, they’ll have to classify that under HFT. Or if they’ve bought bonds just for a bit of safety knowing they can sell it whenever they need to — whether in 6 months or 2 years — they can bucket it in the AFS category.

And the thing with the HFT and AFS categories is that because bonds can be sold at any given time, the RBI has told banks that the value must be ‘marked to market’. This is just a jargon-heavy way of saying that if you buy a bond for ₹100 and it falls to ₹98, then you must reveal that loss in your financial statements.

On the other hand, the HTM category simply means that a bank can buy a bond with the intention of never selling it. They’ll hold on to it for dear life till it matures on its own.

And when Jefferies crunched the numbers of the largest banks in India, they found that over 75% of these bond investments are typically in the HTM segment. Except for Kotak Mahindra Bank which has only 45% stowed away as HTM.

So at the moment, this means even when the central bank increases interest rates and the value of bonds traded in the market falls, banks don’t need to worry about the HTM portion. They don’t need to show these temporary losses in their books. They can simply say, “Look, we bought these bonds for ₹100. And these bonds will mature in 5 years. When it does, we’ll get back what was promised. We aren’t planning to sell any of it before maturity anyway.”

This way, they can just keep showing the ₹100 value on their books. Even if the bond changes hands in the market at a lower price.

And if there’s no loss on the books, investors won’t be too worried.

Now even if the rules around HTM change and it has to be marked to market, Jefferies thinks the impact won’t be catastrophic for banks.

There’s one more thing. A few years ago, the RBI told banks to play it safe. During the good times, when interest rates fall and banks sell bonds under AFS and HFT to reap profits, they need to set a bit of it aside into an Investment Fluctuation Reserve (IFR). The monies in this reserve will be a shock absorber during times like today when interest rates head north and bonds lose value.

Smart, no?

Secondly, we need to remember that over 60% of the monies that banks raise as deposits are doled out as loans. It could be to people like you and me who need a long-term housing loan. Or to corporates who’re looking to expand their manufacturing. Maybe build a new plant or two. And banks are smart, when the interest rates are hiked, they rush to reprice these loan rates quickly. They don’t waste time twiddling their thumbs. Because time is money!

On the other hand, they don’t raise rates on deposits that quickly. They take their own sweet time because they don’t want to pay out a higher interest to us. They want to make hay while the sun shines.

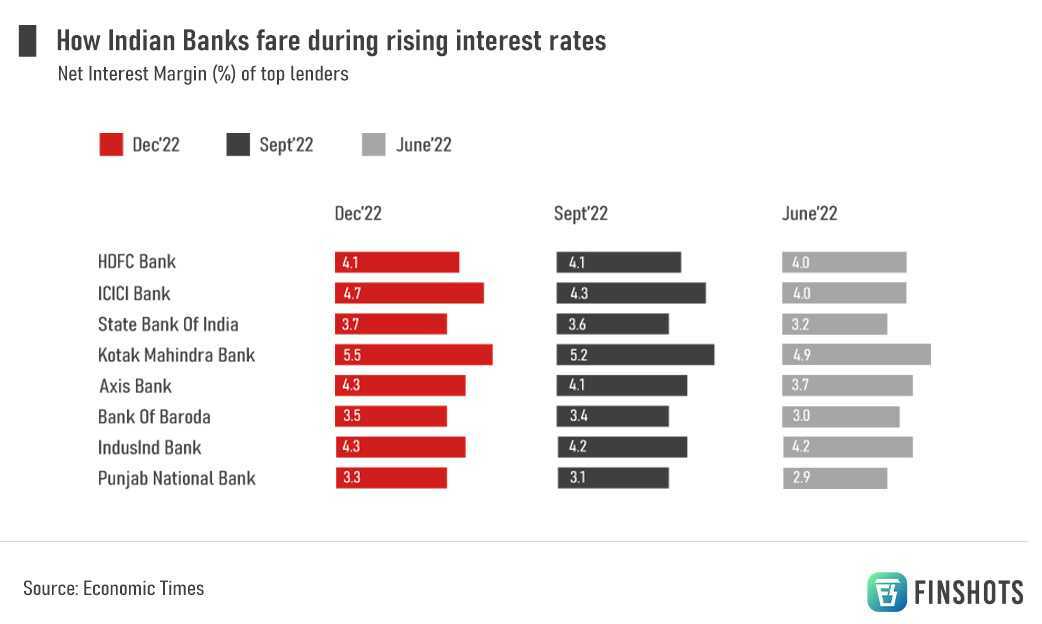

So there’s a lag between loan rates and deposit rates. And that extra money shows up in the margins of banks. For instance, ICICI Bank’s Net Interest Margin (NIM) rose from 4% in June 2022 to 4.7% in December 2022. Kotak Mahindra Bank’s NIM jumped from 4.9% to 5.5%. And State Bank of India’s NIM inched north from 3.2% to 3.7%.

Put these two things together and you’ll see why a rising interest rate doesn’t affect Indian banks too badly. At least initially.

But there’s still a speed bump that banks will have to deal with.

See, in our first story this year — India is ready to lend big in 2023 — we said how credit growth is soaring at its highest level in over a decade . Everyone was borrowing money. Industrialists. Agriculturalists. People like you and me. And banks were doling out a lot of money. But, deposits aren’t growing at the same pace. People aren’t keeping too much money in the bank. And the only way that banks can attract deposits is to raise the rates significantly. That’s the only way they can conduct their business. And when that happens, the NIMs could compress significantly.

That’s the part that investors will have to keep a close eye on.

Anyway, as it stands today, maybe there’s no need for us to be overly concerned about the state of our banking system. And with the RBI at the helm, we seem to be in fairly good hands.

Until then…

Don't forget to share this Finshots on Twitter and WhatsApp.