The AI crisis no one’s talking about

In today’s Finshots, we’re talking about the energy crisis that is going unnoticed by the masses.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

When people talk about artificial intelligence, the conversation usually drifts toward chips, algorithms, and trillion-parameter models. The assumption is that if you have enough GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) and enough data, the rest will somehow fall into place. But over the past year, another constraint has started to surface, and it has nothing to do with GPUs or code.

You see, modern AI data centres are nothing like traditional server farms. Hyperscale campuses can demand hundreds of megawatts of continuous power, equivalent to a mid-sized city. Let’s take a look at why with one simple example:

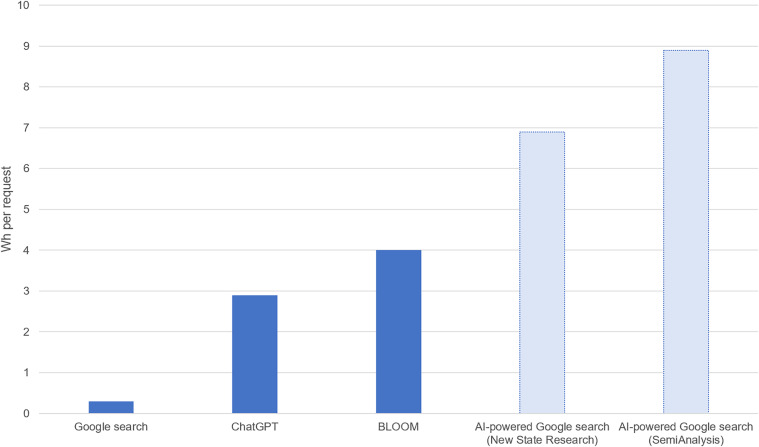

A watt-hour (Wh) is a unit of energy measuring electrical consumption, representing the energy used when one watt of power is consumed for one hour. It's calculated as Watts × Hours and tells us the total amount of energy required to perform something.

A typical Google search consumes about 0.3 Wh of electricity. However, one ChatGPT request consumes about 2.9 Wh of electricity. Considering 9 billion searches a day, this would require about 10 TWh of additional electricity in 1 year. And all of these are rerouted only to a handful of servers that these companies run.

The problem is that power grids were never designed for such a demand to appear this quickly in a single location. Transmission lines, substations, and grid upgrades take years to plan and build. AI infrastructure, on the other hand, is advancing in a matter of months. Meanwhile, each major AI advancement demands significantly more energy than the last.

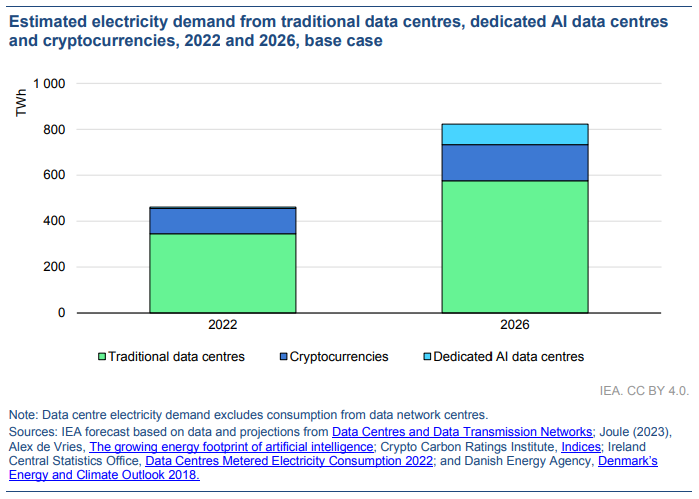

AI’s energy demand is set to go from just 8 TWh in 2024 to a staggering 652 TWh by 2030. That’s over an 80x increase in electricity consumption just by AI in 6 years. We can clearly see increased demand in this estimate by the IEA:

Compared to 2022, this demand for AI data centres in 2026 is set to grow immensely.

And that gap is now being bridged in a way that we probably never expected.

One of OpenAI’s data centre partners, Crusoe Energy, has ordered 29 gas turbines from Boom Supersonic to power its facilities. Yup, you read that right. The company that is set to bring back supersonic flight commercially is also about to help power your late-night ChatGPT requests.

Sidebar: Supersonic flights are aircraft designed to transport passengers at speeds faster than the speed of sound. They were banned in the US and most other regions around the world due to noise pollution from sonic booms. However, that ban was lifted in June 2025 through a US presidential executive order.

And they’re not the only company. Elon Musk’s xAI is already using large methane-fuelled turbines to keep its AI clusters running (and has also been fined for it). Retired aircraft engines like the PE6000, once bolted to long-haul aircraft and military transports, are being converted into mobile power plants.

This also makes sense from the point of view of reducing waste. Rather than scrapping jets entirely at the end of their flight lives, these engines find a second life in the energy sector, and that shift could unlock economic value beyond data centre operations. Park them near a data centre, hook them up to a fuel supply, and you have off-grid power in a matter of days.

What this trend really shows is a contradiction at the heart of the AI boom. Some of the most advanced computing systems ever built are now relying on aviation hardware and burning fossil fuels just to stay online. These turbines are efficient for what they are, but they were never meant to underpin the digital economy. And yet, demand has become so intense that most available industrial turbines are already sold out through 2029.

But this also creates an unexpected upside. Since decommissioned aircraft no longer have to be fully scrapped, that creates a new opportunity for the Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) sector. Countries with good MRO capabilities can refurbish, adapt, and maintain these turbines for stationary use.

And India, which is actively pushing both data centre investment and domestic MRO capacity through tax and infrastructure incentives, sits right at this intersection. It expands the addressable market for engine specialists by adding energy power conversion to their repertoire. Firms experienced in high-precision engine work are uniquely placed to capture this shift, because no one else has matching tech and certification skills for heavy turbine work.

However, the environmental cost is also hard to ignore.

Let’s take methane turbines, for instance. They emit harmful nitrogen oxides into the air, which are known to cause cancer and respiratory diseases such as asthma.

These repurposed jet engines emit significant amounts of carbon dioxide, too. After all, they are meant as temporary solutions. But the risk is that temporary becomes semi-permanent. As more data centres come online and grid connections lag, stopgap power could turn into a structural feature of AI infrastructure. That would push local pollution higher and complicate decarbonisation targets, especially in regions already struggling with air quality.

More importantly, this points to a deeper problem. The grid itself is not ready for sustained, concentrated loads of this magnitude. Instead of waiting for utilities to catch up, companies are taking energy generation into their own hands. That shift blurs the line between technology firms and power producers, and it changes who bears responsibility for emissions and reliability.

In fact, some of the largest players are already looking beyond jet engines. Amazon and Google have both signalled interest in powering future data centres with small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs). And their logic is straightforward. Nuclear energy offers continuous, low-carbon power without the intermittency problems of wind and solar.

SMRs, in particular, promise faster construction, lower upfront costs, and better containment compared to traditional reactors, and they are not a near-term fix, but a bet on where this problem eventually will go. Seen this way, jet engines are not the solution. They are the symptom.

They tell us that as AI scales, its true bottleneck may not only be chips or data. It may be electricity. And until grids adapt to that reality, companies will keep reaching for whatever works, even if it looks outdated.

Sure, for countries like India, there is a chance to build a new revenue stream around refurbishing and operating turbine-based power through a strengthened MRO ecosystem. However, there is a policy challenge in ensuring that emergency solutions do not undermine long-term climate goals.

Fixing this permanently will require a combination of grid upgrades, faster transmission build-outs, and genuinely scalable clean power. SMRs may play a role. So will a better plan to align data centre locations with renewable capacity.

Until then, regulators may be forced to walk a tightrope, allowing flexibility for critical digital infrastructure while placing limits on carbon-intensive backup power.

So yeah, jet engines may keep AI servers running for now, but it also makes one thing clear:

The future of artificial intelligence will be shaped as much by energy policy as by algorithms.

If this story helped you understand the AI energy crisis better, feel free to share it with your friends, family or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

Did you know? Nearly half of Indians are unaware of term insurance and its benefits. Are you among them?

If yes, don't wait until it's too late.

Term insurance is one of the most affordable and smartest steps you can take for your family’s financial health. It ensures they do not face a financial burden if something happens to you.

Ditto's IRDAI-Certified advisors can guide you to the right plan. Book a FREE consultation and find what coverage suits your needs.

We promise: No spam, only honest advice!