Breaking down the PhonePe DRHP

In today’s Finshots, we dive into PhonePe’s DRHP (Draft Red Herring Prospectus).

But before we begin, if you love keeping up with the buzz in business and finance, make sure to subscribe and join the Finshots club, loved by over 5 lakh readers.

Already a subscriber or reading this on the app? You’re all set. Go ahead and enjoy the story!

The Story

Last week, PhonePe finally dropped its Updated DRHP (Draft Red Herring Prospectus). And the first thing it tells you is that this IPO isn’t about raising money to run or expand the business. It’s mostly about giving early investors a way out.

For context, PhonePe is planning an IPO worth roughly ₹13,500 crore. But the entire issue is an Offer For Sale. That means PhonePe isn’t issuing any new shares and won’t receive a single rupee from the IPO. Instead, existing shareholders, Tiger Global and Microsoft Global Finance are exiting, while Walmart through its entity, WM Digital Commerce Holdings, is offloading about 9% of its stake to the public.

That detail changes how you should read this IPO.

Because when a company isn’t raising fresh capital, it’s effectively telling you that it doesn’t need the money for growth. And that’s true for PhonePe. It already sits on a healthy cash pile of around ₹1,100 crore, built over years of private funding and, more recently, improving cash flows.

So in a way, PhonePe is coming to the market saying, “We’re not here because we need your money to operate; we’re here because we want to be publicly owned.”

But to decide if taking a piece of PhonePe’s ownership is worth it, the obvious next question is how PhonePe actually makes money. And that’s where the story really begins.

After all, for most users, PhonePe looks like a free payments app.

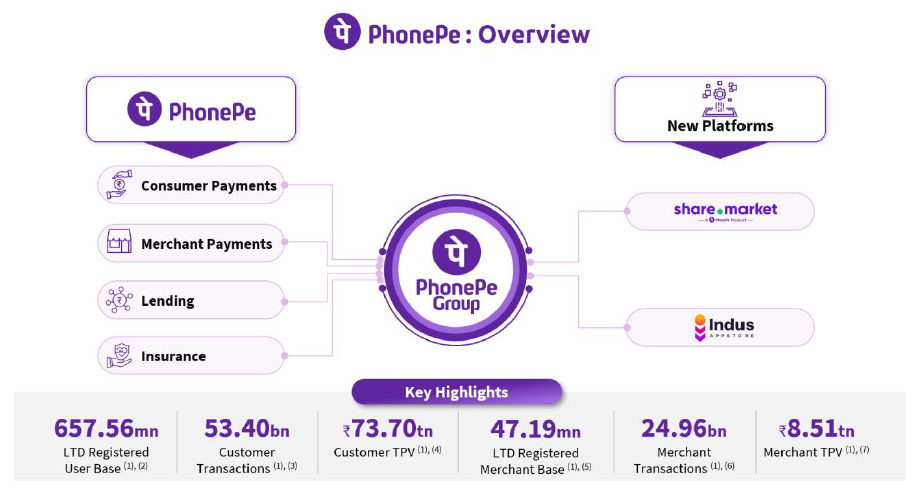

But PhonePe isn’t just that. Over time, it has built an ecosystem made up of three distinct platforms.

The first is the PhonePe Platform, which is its main business. This includes the consumer-facing app that you and I use to send money, pay bills, recharge our phones, and check balances. It also includes the PhonePe Business App, where merchants accept digital payments.

Then there’s Share.Market, a stock broking and mutual funds app designed to help everyday Indians invest. And finally, there’s the Indus Appstore, an Indian alternative to the Google Play Store.

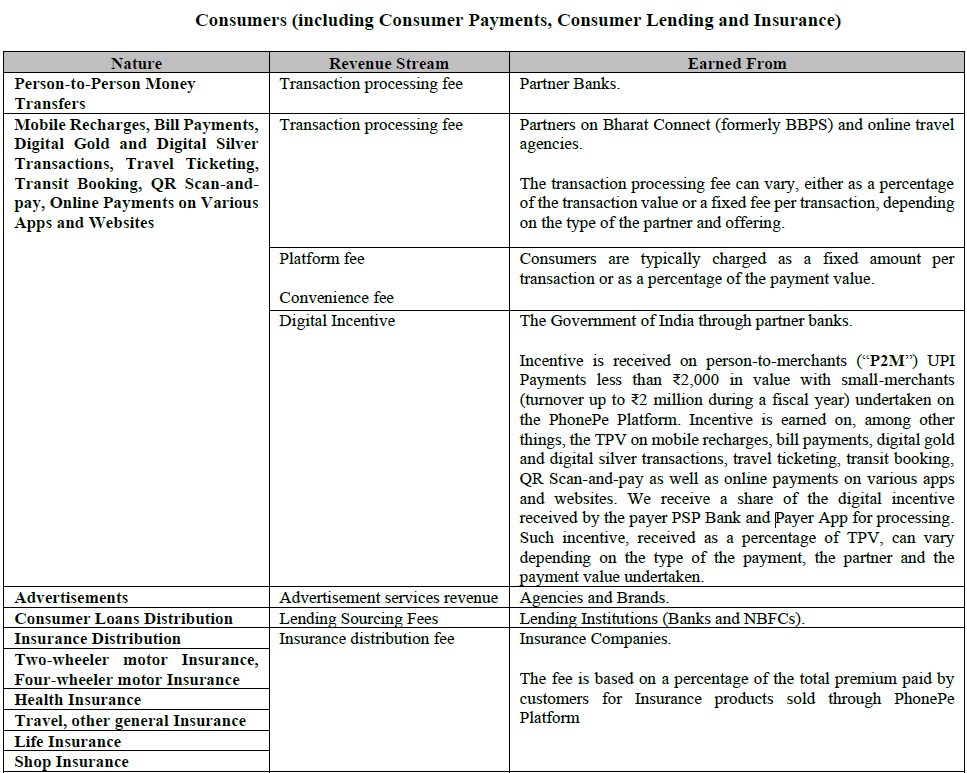

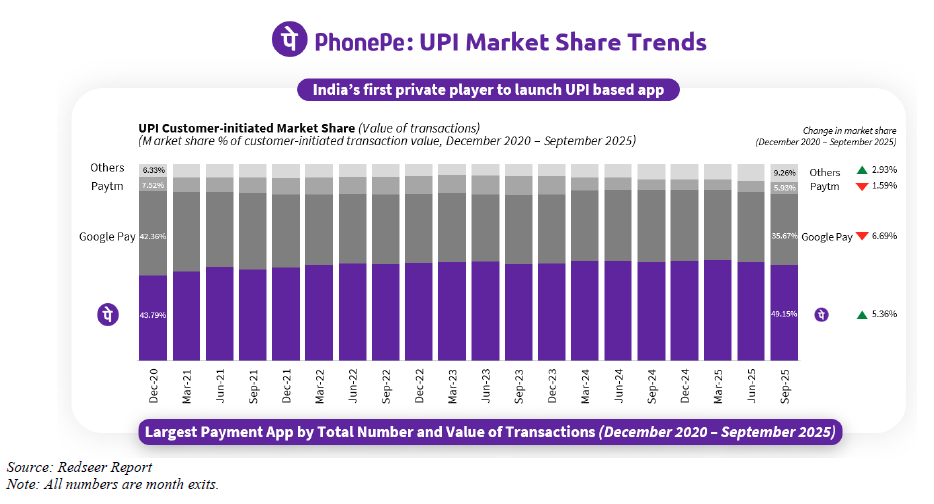

Still, the reason you mostly see PhonePe as an app for sending money, scanning QR codes, and paying bills isn’t accidental. Even though about 99% of its revenue comes from the PhonePe Platform, and a large part of that is tied to consumer payments, PhonePe doesn’t make meaningful money from UPI transactions. Person-to-person transfers, QR payments at kirana stores, and basic bill payments are either loss-making or close to zero-margin.

And that’s simply because PhonePe can’t charge users or merchants freely without risking its scale.

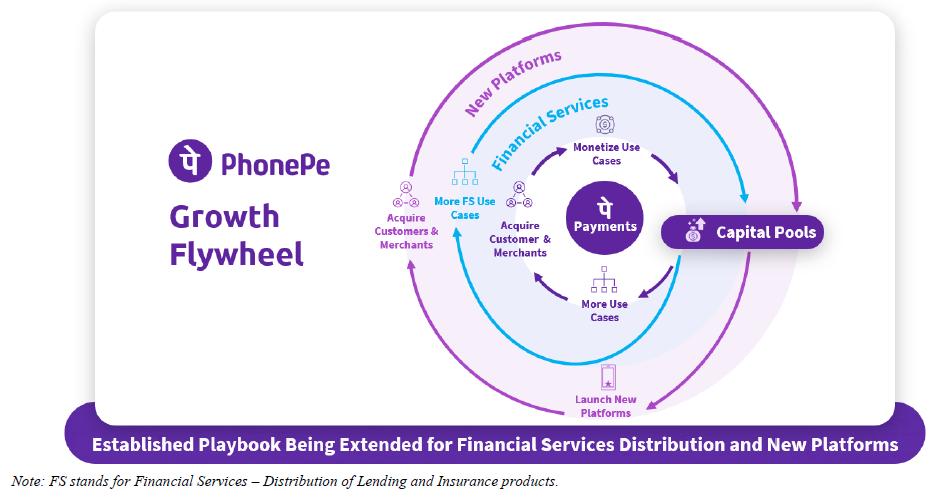

But PhonePe has never treated payments as the end product. Payments are just the entry point.

What payments give PhonePe is habit, trust, and distribution. Hundreds of millions of Indians use PhonePe multiple times a day. In fact, about 30 crore consumer transactions happen on the app every single day. That means PhonePe knows where you spend money, when you spend it, what your bank balance looks like, and even when you might need money. And that makes PhonePe far more valuable than a simple payments utility. It turns into a financial distribution platform.

The real money starts showing up once you move beyond pure payments.

One major revenue stream comes from merchants, especially online merchants. A QR code at a roadside shop doesn’t generate much revenue. But PhonePe’s payment gateway for e-commerce businesses does. Online merchants pay transaction fees when customers use UPI, cards, wallets, or netbanking through PhonePe’s gateway. On top of that, PhonePe sells merchant devices like SmartSpeakers and card machines, offers faster settlements and reconciliation tools, and increasingly, advertising. Merchants can pay PhonePe to promote their business inside the app to nearby or relevant users. Each of these revenue streams may look small on its own, but at PhonePe’s scale, they add up to steady, recurring income.

The most profitable part of PhonePe’s business, though, is financial services distribution — especially lending.

PhonePe works as a lending service provider, connecting users and merchants with banks and NBFCs (Non-Banking Financial Companies). It uses transaction data to identify eligible borrowers, handles onboarding and repayment flows, and earns commissions from lending partners for every loan disbursed. Since it doesn’t carry these loans on its own balance sheet, the business is asset-light and highly scalable. And the margins here are significantly higher than in payments.

Insurance distribution follows a similar playbook. PhonePe sells health, life, and general insurance products from insurers, earns commissions, and takes on no underwriting risk. Insurance isn’t a high-frequency purchase, but each sale carries healthy margins. Over time, as users grow more comfortable buying financial products digitally, this business can quietly compound.

Together, lending and insurance explain how PhonePe has managed to make its core platform profitable at an operating level, even while payments themselves remain free.

Payments bring users in. Financial products monetise them.

That said, these products currently contribute only about 7–11% of PhonePe’s overall revenue, leaving plenty of room to grow.

Beyond this, PhonePe is also placing long-term bets that aren’t meaningful revenue drivers yet. Share.Market, its stockbroking and mutual funds platform we spoke about earlier, is one such bet. It operates in a fiercely competitive space and is unlikely to contribute much to profits in the short term. But PhonePe believes its massive user base gives it a low-cost way to acquire investors over time.

The Indus Appstore is similar. It’s more strategic than commercial for now and an attempt to build a Made-in-India alternative to global app stores, offer better terms to developers, and gain more control over distribution. Monetisation here will take time, and success is far from guaranteed.

Put simply, PhonePe today makes money mainly from merchant services, lending distribution, insurance commissions, and advertising. Payments are the glue, not the profit centre. And the newer platforms are still scaling, with much more uncertainty around how big they eventually become.

But PhonePe thinks about growth like a spinning wheel that keeps gaining momentum. The more people use the platform, the more transactions happen. More transactions mean richer data about what users want and how they behave. And that data allows PhonePe to build new products in investments, insurance, and lending. These new products, in turn, have the potential to generate additional revenue and improve profitability.

The cycle then repeats, creating what PhonePe believes could be a sustainable growth engine over the long term.

A big part of making this flywheel work is where PhonePe is focusing its expansion. Much of its growth is coming from Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities. In fact, about 65% of PhonePe’s users come from smaller cities, not metros. And that matters because financial services in these regions are still deeply underpenetrated. Many people don’t have access to investment accounts, insurance, or formal credit. PhonePe sees this gap as a massive opportunity to bring first-time users into the financial system.

This reach isn’t limited to consumers. PhonePe’s merchant network already spans 98% of India’s postal codes, giving it deep geographic penetration, even in remote areas. That kind of footprint makes it easier to scale new products without starting from scratch.

The financials reflect this momentum. In FY25, PhonePe reported revenue from operations of ₹7,115 crore, growing at a 56% CAGR (compound annual growth rate) over the last two years. The company is still loss-making, with losses of ₹1,727 crore in FY25, but those losses have narrowed sharply from ₹2,796 crore in FY23. That’s a sign that scale is starting to work in its favour.

The clearest evidence shows up in operating profitability. PhonePe’s adjusted EBITDA margin (operating profit) has swung from -12.88% in FY23 to a positive 20.76% in FY25. In simple terms, the core business has moved from burning cash to generating operating profits. That’s a crucial shift as PhonePe looks to sustain growth going forward.

That brings us to the risks. Because for all its scale and improving finances, PhonePe’s business model isn’t without its weak spots.

The biggest risk sitting over PhonePe is regulation. The company operates in areas that are tightly controlled by regulators, and while PhonePe follows the rules today, the rules themselves can change. UPI pricing is regulated. Lending commissions are governed by RBI norms. Insurance payouts and commissions are overseen by IRDAI. If regulators decide to cap commissions, restrict how lending platforms operate, or tighten rules around default-loss guarantees (where platforms promise to absorb initial losses if borrowers default), PhonePe's most profitable businesses could see their margins shrink almost overnight.

One example of how this regulatory risk could play out is UPI itself. NPCI has proposed a rule that would cap any single app at 30% of all UPI transactions in the system, a limit that’s currently deferred until December 31, 2026. At 49%, PhonePe already sits close to that threshold. If the cap is enforced, it could limit PhonePe’s ability to onboard new users or grow transaction volumes further. And while payments themselves don’t make meaningful money, they power everything else. Slower payment growth would mean weaker engagement, less data, and fewer opportunities to sell loans, insurance, merchant services, and ads.

The second major risk is PhonePe’s dependence on UPI and partner banks. Almost everything PhonePe does runs on UPI. But UPI isn’t PhonePe’s infrastructure. It depends on NPCI systems and sponsor banks to process transactions smoothly. If there are technical glitches, policy changes, transaction limits, or bank-related issues, the user experience takes a hit.

The third risk lies in competition, especially when it comes to monetisation. PhonePe’s future profits depend heavily on earning commissions from lending and insurance. But banks, NBFCs, fintech startups, and even rival apps are all chasing the same customers. If lenders push back on commissions or competitors offer better terms, PhonePe may have to give up margins to keep volumes high. Growth might continue, but profitability could stall.

And then there’s valuation. Since this is an OFS-driven IPO with marquee investors exiting, public market investors will be watching closely. They’ll want to see steady improvements in growth, margins, and cash flows after listing — not just big user numbers.

Put it all together, and the PhonePe DRHP tells a fairly clear story. This is a scaled platform using payments to power a profitable financial distribution business, while placing long-term bets on new digital platforms.

And whether it succeeds in the public markets will depend less on how many UPI transactions it processes, and far more on how well it converts that scale into sustainable profits.

Until then…

Don’t forget to share this story with a friend, family member or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

Myth Alert: I'm Too Young to Buy Life Insurance!

The other day, one of our founders was chatting with a friend who thought life insurance was something you buy in your 40s. He was shocked that it was still a widely held belief.

Fact: Life Insurance acts as a safety net for your family. The younger you are, the cheaper it is. And the best part? Once you buy it, the premium remains unchanged no matter how old you get.

Unsure where to begin or need help picking the right plan? Book a FREE consultation with Ditto's IRDAI-Certified advisors today.