Would you put your money in a 100-year bond?

Google’s parent, Alphabet, just issued a 100-year bond. So in today’s Finshots, we tell you why anyone would buy something they’ll never live to see paid back in full.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

In 1997, Motorola issued a 100-year bond. In simple terms, it borrowed money from investors and promised to repay the principal only after a full century. It was widely seen as the last century bond by a tech firm, although, technically, Rockwell Automation, a software company, issued one a year later. Still, we’ll stick with Motorola as it’s the name most of us recognise.

Motorola raised $300 million at an interest rate of 5.22%. That meant even though it would repay the borrowed amount only after 100 years, it had to pay 5.22% interest every single year to bondholders no matter how interest rates moved over time.

And at the time, this wasn’t unusual. In fact, 1997 saw a record 41 century bonds issued as yields (interest rates) on long-term 30-year US Treasury bonds had fallen sharply (from 7.8% in 1994 to about 5% by the end of 1997). And as rates dropped, tech companies riding the dot com boom locked in long-term debt at relatively cheap rates before conditions changed.

In hindsight that wasn’t a bad call. Recent long-term Motorola bonds now trade at yields closer to 6%. Yet the company still pays just 5.22% on that 1997 bond. That’s because bond prices and yields move in opposite directions — when yields rise, bond prices fall, and vice versa.

Sidebar: The simple logic behind this is that if interest rates rise and new bonds start offering higher coupon rates (the interest paid on the bond’s face value), the bond you’re holding suddenly looks less attractive. So if you want to sell it before it matures, you’ll probably have to offer it below face value to tempt buyers.

On the flip side, if interest rates fall, your bond becomes more appealing. Buyers may then be willing to pay more than its face value to own it.

The only reason it has been labelled so problematic by investors like Michael Burry is that when Motorola issued that 100-year bond, it was a top-25 company in America by market cap and revenue. At one point, it was ranked #1 in the US, even ahead of Microsoft. But fast forward to today, it sits around the 232nd spot, with roughly just $11 billion in sales. It lost dominance in the very business that made it famous — mobile phones, but it still has to service that debt until 2097.

That’s exactly why 100-year bonds aren’t a popular way to raise money right now. As a company, you don’t know whether you’ll even exist a century from today. And even if you do, whether your business will still matter. Take the example of JC Penney, an American retail chain. It issued a $500 million century bond in 1997 and went bankrupt just 23 years later. Sure, bondholders do get paid before equity shareholders in the event of a shutdown, but it’s still a serious risk.

And yet, you’ve probably seen the news. Alphabet, Google’s parent company, recently borrowed £1 billion by issuing a 100-year bond in the European market. And the demand was almost 10 times more than what Alphabet was offering.

This isn’t the only bond Alphabet has sold. It has also issued shorter-term bonds that mature anywhere between 3 and 32 years, mostly in Pounds and Swiss Francs. But interestingly, it’s the 100-year bond that attracted the most interest from investors.

Which naturally brings up two questions. Why is Google issuing something as rare as a 100-year bond, and that too in the European market? And who on earth is buying it?

After all, as an investor, you’re not going to be around when this bond finally matures. So what exactly are buyers planning to do with something they’ll never see pay back in full?

Let’s answer the first question first.

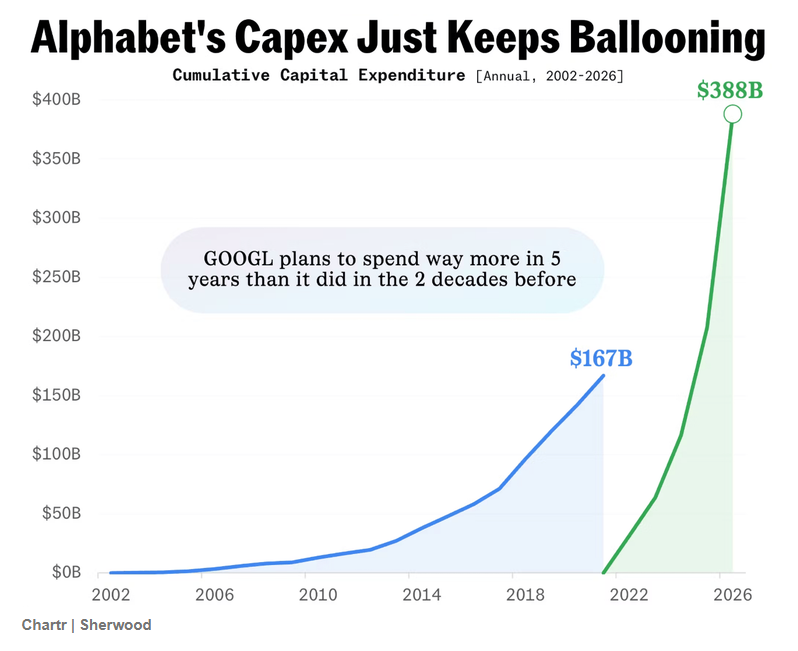

Alphabet plans to spend $185 billion in capital expenditure this year, largely on AI infrastructure, data centres and next-gen tech. Now sure, it generates over $73 billion in free cash flow annually and has about $126 billion in cash on its books. But it can’t simply drain its reserves. These investments will stretch for years, and it knows that more funding will be needed along the way. In fact, its planned capex for 2026 alone will push its total spending over the last five years to nearly double what it spent in the two decades up to 2018.

But the reason it’s chasing a 100-year bond is probably because for one, it locks in a 6.125% interest rate for a very long time, regardless of where rates go in the future. Another reason is demand. UK pension funds and insurance companies are actively looking for long-term bonds. They have obligations such as pensions, insurance payouts, endowments, that stretch decades ahead. And long-term bonds fit that need perfectly as it gives them a steady income for many years. That’s also why other US companies like Thermo Fisher and Caterpillar issued long-term bonds in Swiss Francs recently. Europe has large investors who prefer lending in their own currency.

For Alphabet, raising money there also spreads its borrowing across different markets. If currency movements work in its favour, its effective borrowing cost in dollars could even fall. Of course, currencies can move the other way too. But there are ways to hedge that risk — just not something we’ll get into in this story.

Well, that kind of answers both questions. Large institutions with long-term obligations are happy to buy these bonds because they match their future payouts. But that doesn’t mean regular investors can’t buy them too. Which raises another interesting question. What exactly do they do with something that lasts 100 years?

See, investors don’t always buy a bond just to hold it till maturity. There are other reasons too.

One is generational wealth. You buy a 100-year bond and earn interest every year. When you’re no longer around, your family continues to receive that income. And whoever is around in the 100th year eventually gets the principal back. It becomes a long stream of predictable income passed down the line.

The second reason is trading. Bonds can be traded just like stocks. So a 100-year bond doesn’t mean you’re locked in for a century. You can buy it today and sell it later. If you believe that interest rates will fall (remember what we discussed earlier — when rates fall, bond prices rise), the value of your bond could increase, allowing you to sell it at a profit. For investors who expect rates to drop over time, that’s a clear opportunity.

Another thing worth understanding is something called a bond’s duration. Put simply, it tells you how long, on average, it takes to recover what you paid for the bond through its interest payments and the final principal repayment. For Alphabet’s 100-year bond, the duration is just under 17 years. That’s far shorter than 100, and actually a fairly reasonable time horizon for many investors.

Duration also gives you a rough idea of how sensitive a bond is to interest rate changes. The higher the number, the more your bond’s price will move when interest rates change. As a rule of thumb, if a bond has a 10-year duration, a 1% move in interest rates could change its price by about 10%. The same logic applies here. With a duration of around 17 years, even a small 0.25% rate cut could push the bond’s price up meaningfully, by about 4.25% (and vice versa). That said, remember that this is only an approximation. It works best for small changes in interest rates. For larger moves, the actual price change won’t be perfectly linear.

So yeah, if you’re reading headlines that scream investors are simply betting that Alphabet will still be around in 2126, that’s probably not the real reason they’re putting money into this bond.

And that’s pretty much the long and short of the mystery behind Alphabet’s rare 100-year bond.

Until next time…

If this story helped you understand 100-year bonds and why investors are willing to bet on them, share it with friends who’ve been Googling about them. Or even family and curious folks who might enjoy learning something new via WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and X.

If you’re an Indian living abroad, here’s a question.

If something were to happen to you, would your family in India know how to deal with a foreign insurer? Different laws. Different time zones. And different claim processes.

Indian term insurance can make claims simpler for families back home, and it’s often cheaper too.

But there are caveats: medical underwriting abroad, rider availability, country restrictions, tax implications, and documentation requirements.

So we’ve explained everything NRIs need to know about buying term insurance in India.

Check out our detailed guide on Term Insurance for NRIs in India here.