Why S&P finally raised India’s credit rating

In today’s Finshots, we tell you why S&P Global hadn’t upgraded India’s sovereign credit rating for 18 years, and why it has finally done so now.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

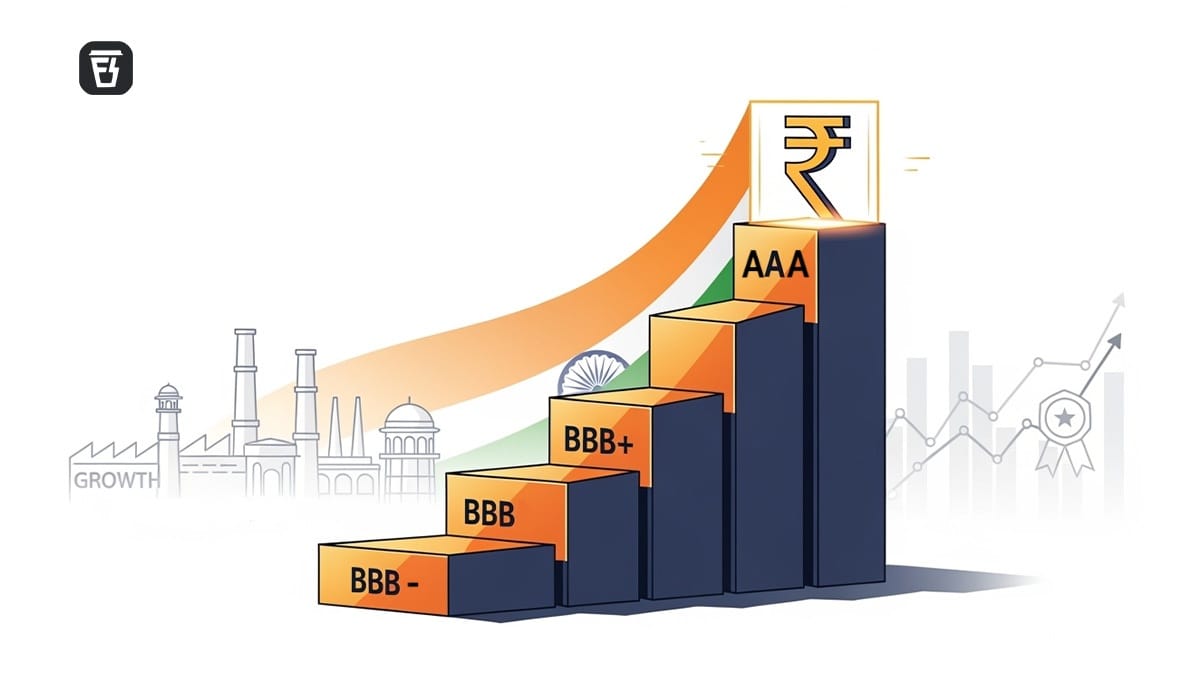

A few days ago, India got a sovereign credit rating upgrade from S&P Global. We moved up from BBB− to BBB. And if that feels like a small step, remember this — India’s last upgrade to BBB− happened way back in 2007. So this one comes after an 18-year wait.

Now, if that sounds a little too technical, let’s break it down.

Think of a credit rating as nothing more than a report card on someone’s ability to repay loans. It could be a person, a company or even a government. So when we say sovereign credit rating, we’re basically talking about a government’s credit score. Why does a government even need that, you ask?

Well, running a country isn’t cheap. Taxes and export earnings alone don’t always cover the bill. So governments often have to borrow, whether from global institutions like the IMF or World Bank, from other countries or even from investors worldwide. And one popular way they do this is by issuing government bonds, which are basically IOUs. The government takes money now, promises to pay interest along the way and returns the full amount when the bond matures.

But before lending money, investors need to know: Can this government really pay me back? That’s where sovereign credit ratings come in.

And S&P isn’t the only one doing this. It, along with Moody’s and Fitch, controls nearly 95% of all credit ratings in global markets. Which is why when any of them upgrades India, the world takes notice.

Now about those alphabets — BBB, AAA, D — they’re just part of a scale. At S&P, AAA is the gold standard, the safest of the safe. BBB− is the lowest rung of what’s called “investment grade”. Anything below that is politely called “junk”. So India’s new BBB rating simply tells global investors: “Your money’s relatively safe here. But if things go wrong, repayment capacity could get tested.”

So yeah, one minus sign dropped off. But what does it actually mean for us?

Well, investor confidence gets a nice boost. That could mean India finds a bigger place in major global bond indices like JPMorgan’s or Bloomberg’s. And here’s why that matters. Many large funds automatically pour money into countries listed in these indices. So if India gets a higher weight, billions of dollars could flow into Indian bonds. More foreign money, more liquidity and lower borrowing costs for the government because lenders now see less risk.

That has already played out in the markets. Soon after the upgrade, India’s 10-year bond yield (interest rate) fell from 6.51% to 6.40%. Of course, it bounced back later because bond yields move on more than just credit ratings. For instance, when the Prime Minister hinted at a big GST reform, yields spiked again. Why? Because investors worried that the new structure could reduce revenues or create uncertainty over how money flows to the Centre and states, potentially weakening the government’s finances and its ability to repay debts.

But while you’ve probably seen all that in the headlines, here’s the real question: why did it take S&P 18 long years to upgrade India? And why now?

The short answer — India’s fiscal health.

To begin with, India’s public debt (money the government owes) has been a thorn in the side for decades. For context, it was about 60% of GDP in the 1980s, went up to 70% in the 1990s and 80% in the 2000s. After dipping a bit, COVID hit, and debt shot up close to 90% of GDP in 2020–21. Alongside this, the fiscal deficit (basically when government spending outstrips income) often stayed in the 7–8% range. And during COVID, it blew up to a record 13.1%.

Interest payments added more pressure. Even today, India spends about 5% of GDP just on servicing old debt. That’s more than what goes into education, health or even capital expenditure on new infrastructure. And here’s another interesting bit. In the past 40 years, India’s managed a primary surplus (income exceeding expenses before interest payments) just once — in 2007–08.

By FY25, central government debt touched ₹197 lakh crores, while states added another ₹94 lakh crores. That’s nearly double what it was just seven years ago. Compare that to other emerging economies, where debt-to-GDP averages closer to 60% and fiscal deficits around 5% and you can see why agencies like S&P were reluctant to budge.

But things look a little better now. The overall debt-to-GDP ratio (central and states put together) has eased to around 83%. The overall fiscal deficit is down to 7.8%. Growth, though slower than before, is still steady at about 6.5% — among the best globally. And if this trajectory continues, debt could fall to around 78% of GDP by 2030, with deficits easing as well. That gives rating agencies some comfort.

Another sticking point was India’s weak tax-to-GDP ratio. It peaked at 12.58% in 2007–08 but later slipped. It’s now crawling back up to 11.6% and could inch towards 12% by FY26. Still not great, but moving in the right direction.

Add to that the bouts of high inflation and swings in interest rates, and you’ve got another headache. Rising prices eat into investors’ returns, drag down growth and even weaken the currency — all of which make rating agencies think twice before handing out an upgrade.

And that’s really why S&P played it safe all these years. They wanted long-term proof, not short bursts of good numbers. Sustained fiscal improvement, higher tax revenues, and structural reforms were their checklist. And now, after nearly two decades, they seem convinced enough to give India that small but significant push from BBB− to BBB.

But that doesn’t mean it’s time to pop the champagne just yet.

Remember that line we mentioned earlier — “if things go wrong, repayment capacity could get tested”? Yeah, that’s the catch.

Meaning, if we’d like to keep our rating upgrade, India has to do a lot of things right with its economy. S&P has already hinted that a further upgrade is possible, but only if India manages to narrow its fiscal deficit in a big way. In fact, they’ve said the net change in government debt needs to consistently stay below 6% of GDP.

While that sounds neat on paper, the twist is that S&P projects India’s combined fiscal deficit will only dip to about 6.6% by the end of the decade. So that target feels like trying to touch the ceiling while standing on your tiptoes. You’re close, but not quite there.

And then there’s the debt problem. It needs to shrink meaningfully too. But that looks tricky right now, especially with both direct and indirect tax rates trending downwards. Sure, lower taxes could mean more people filing returns, more consumption led spending and eventually better revenues. But until that plays out, the math looks a bit shaky.

The only comforting sign is inflation. Headline inflation — which combines core items like education, rent, healthcare and transport with non-core items like food and fuel, has eased closer to around 2%. That gave the RBI enough confidence to cut interest rates back in February, a move that could support growth and also make managing debt a little easier for the government in the short run.

But when the next upgrade will come is honestly anyone’s guess, and whether it will come at all is something we’ll just have to wait and see.

Until then…

Don’t forget to share this story on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

A message to all the breadwinners

You work hard; you provide and make sacrifices so your family can live comfortably. But imagine when you're not around. Would your family be okay financially? That’s the peace of mind term insurance brings. If you want to learn more, book a FREE consultation with a Ditto advisor today.