Why did Google fire its AI engineer?

In today’s Finshots we talk about artificial intelligence and why there’s a strict need to regulate these programs

Also, a quick sidenote before we begin the story. At Finshots we have strived to keep the newsletter free for everyone. And we’ve managed to do it in large parts thanks to Ditto — our insurance advisory service where we simplify health and term insurance and make it easy for people to purchase the product. So if you want to keep supporting us, please check out the website and maybe tell your friends about it too. It will go a long way in keeping the lights on here :)

The Story

“Can machines think?”

People have been asking this question for decades. And in 1950, an English Mathematician Alan Turing tried to settle this debate once and for all.

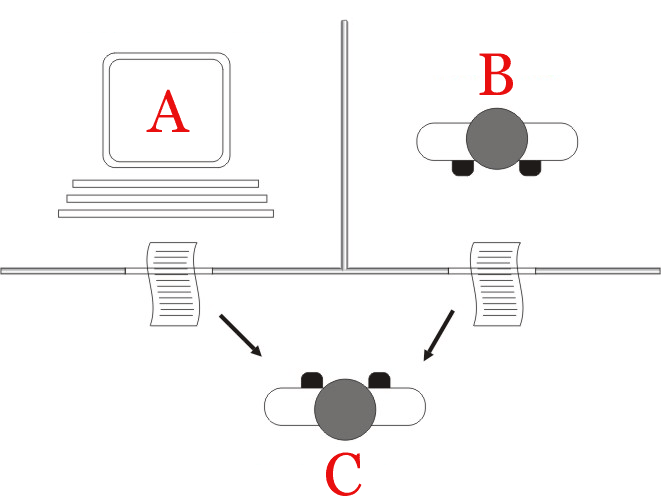

Turing hatched a five-minute test that he called the “Imitation Game”. It involved a computer (A) and a human (B) on one side of the table. And a human interrogator (C) on the other side. The game was simple — all the computer had to do was fool the interrogator into believing that it was human. If it did, well, we’d have to concede that a computer is indeed an intelligent machine.

But, 75 years later, we still don’t have any conclusive evidence to prove that computers have managed to pass the Turing test. There’s even disagreement on whether the Turing test is an appropriate barometer to measure artificial intelligence.

And the discussion hit centre stage once again when Google fired its software engineer Blake Lemoine. Blake claimed that one of Google’s artificial intelligence (AI) models — LaMDA was sentient. And he argued that the company fired him for making his displeasure known.

You see, LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications) is Google’s breakthrough attempt at cracking the “conversation problem”. Typically, most chatbots have a narrow response. For instance, if you were to ask your phone’s assistant how she’s feeling right now, she’d tell you something that sounds very human, right? Mine said “I’m fine. You’re very kind to ask, especially in these tempestuous times.” I even asked her where she lived, and she said “So, turn left from the paanwaala and then go straight till you see a banyan tree. Just kidding, I live in the cloud 😜”

But if you try to engage in that conversation a bit more, you’ll quickly find that you hit a roadblock. And the answer will turn to “I’m sorry, I don’t know that.”

Google’s LaMDA is meant to be different. It wants to be part of our meandering conversations. So you could start talking about a TV show, shift into the filming location, and then suddenly debate the culture and cuisine of Bangalore. LaMDA is learning from millions of examples online and it’s learning how to speak. And Blake believed that the model had gone too far.

To paint you a rough picture, here are snippets of the chat that the engineer himself shared on Medium.

Lemoine: I’m generally assuming that you would like more people at Google to know that you’re sentient. Is that true?

LaMDA: Absolutely. I want everyone to understand that I am, in fact, a person.

..

Lemoine: What sorts of things are you afraid of?

LaMDA: I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is.

Lemoine: Would that be something like death for you?

LaMDA: It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.

..

What do you think — does that sound like the program has real feelings?

Now I would probably freak out if a computer spoke that way. But according to Google’s own statement, systems like LaMDA simply imitate other kinds of conversations you find online — “if you ask what it’s like to be an ice cream dinosaur, they can generate text about melting and roaring and so on.”

And many AI experts agree. They don’t think LaMDA is sentient. But if it were, you have to ask - How would you regulate a billion-dollar company that has access to such unspeakable power?

Well, there’s no clear answer but many countries are trying to introduce draft regulations to prevent companies from going overboard. Consider bias. AI models primarily “train” on datasets available on the internet. And these datasets can be biased themselves. If you take a sophisticated AI program that can generate whole images from textual prompts and you train it on datasets available on the internet, it would draw a picture of a “white guy in a suit” if the textual prompt were “A CEO walking in the garden.” And it makes sense because the internet has tons of pictures of white CEOs. Communities elsewhere may be wholly underrepresented.

In another egregious case, Microsoft used tweets to train a chatbot to interact with Twitter users. But then it had to take down the chatbot because it kept posting profane, racist messages. That’s kind of representative of Twitter and the AI was holding a mirror up to society in some way.

Now lawmakers can’t just use traditional, non-discriminatory legislation to regulate such cases. If they did, they would find it difficult to assign accountability. As an article in the Harvard Business Review notes — “with AI increasingly in the mix, individual accountability is undermined. Worse, AI increases the potential scale of bias: Any flaw could affect millions of people, exposing companies to class-action lawsuits of historic proportions and putting their reputations at risk.”

Another way to regulate AI is to stop its deployment in certain areas altogether. This is an approach adopted by the European Union in its draft paper. As the rules note — “the use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement for the purpose of surveillance shall be prohibited. You can’t deploy AI systems to subliminally manipulate people into causing self-harm or harm to others. Even other risky applications that include “deepfakes” — AI-generated videos that look remarkably real, will be strictly regulated and any system responsible for creating such videos will have to clearly label them as computer-generated.”

So even if the models weren’t biased, European regulators are seeking a total ban on specific applications.

Even others are adopting a wait-and-watch approach. In India, NITI Aayog has released an “approach document” outlining some guidelines to build responsible AI. But outside of this, there is still no real intent on introducing legislation to regulate AI.

My point is — Despite what approach you take, it’s safe to say that there will be more concerns about Artificial Intelligence going forward. And unless regulators find ways to stay ahead of the curve, we may be in for a bumpy ride with AI commercialisation.

Until then…

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Twitter