Why Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Prize in Economics

On Monday, Harvard economics professor Claudia Goldin made history! She became the first woman to win the coveted Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences solo — meaning she didn’t have to ‘share’ it with another colleague.

So in today’s Finshots, we tell you why she was the chosen one. But before we begin let’s make one thing clear — Goldin didn’t win this prize for one seminal paper that was an aha! moment. She won it for her research spanning decades. But let’s try condensing that, eh?

But before we begin, if you're someone who loves to keep tabs on what's happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven't already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

Women typically earn less than men for the same job. You know it. I know it. The world knows it. In fact, in the US, women earn 82 cents for every dollar earned by men. That’s a pretty massive gender pay gap. It’s not just that. Women end up with less representation on corporate boards. And women-led startups attract less attention and money from venture capitalists.

But how did we end up with this massive divide? And why does it continue to happen?

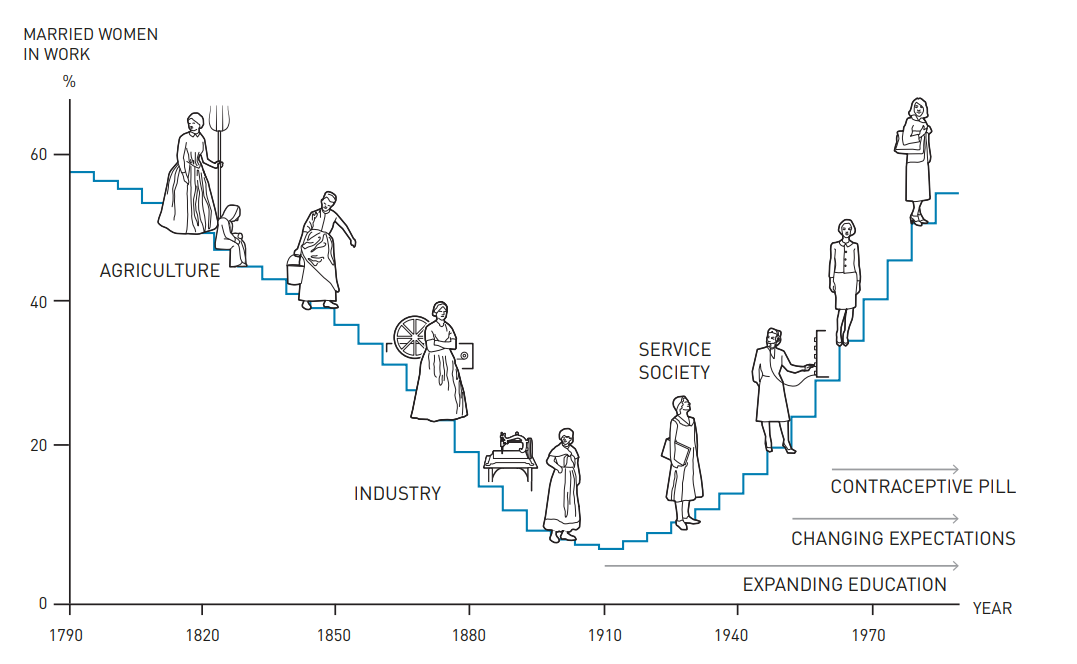

Well, that’s what Claudia Goldin has been trying to answer. And let’s start with what’s probably her most famous contribution — the U-shaped curve.

You see, for a long time, everyone believed that economic growth and women’s participation in the workforce went hand-in-hand. Faster growth meant more women in the workplace. Kind of like a straight-line growth. But in 1990, Goldin showed that this relationship in the US has actually been U-shaped.

To show that, she dug out data spanning over 200 years in the US. And she found that a lot of historical data sets were flawed. Yikes. You see, researchers had often ignored married women in their datasets. They were simply listed as “Wife” in surveys. But what if this “wife” was actually partaking in agricultural activities? Or helping out in the family business? In effect, she should be part of the labour force. But that wasn’t happening. She was being overlooked.

And if those women were included in the labour force, their participation would have been 3x higher than what records had previously indicated.

Source: Nobel Prize website

But then, industrialization came along and the labour force participation rates actually plummeted.

The simple answer — women couldn’t work from home anymore. They lost flexibility. They’d have to go into factories. And that meant combining work and family would be hard. So while single women did join industries, married women dropped out.

It was only in the 1900s when the economy started reorienting towards services and women could access education more easily that things began to change. But still, progress was slow. And that was a bit weird. You’d have expected labour force participation to accelerate along with economic progress. But Goldin pointed out that there were probably two reasons to explain this.

Firstly, there was marriage. Because there were actual rules that prevented women from working in certain roles after marriage. Yup, sounds crazy but it’s true. So as soon as they whispered “I do” at the altar, their employment as teachers or office workers would be terminated. You can see how that would affect labour force participation, right?

But then, there was also the matter of expectations.

You see, in the first half of the 1900s, young women kind of knew they’d have to drop out of the workforce when they got married. So their education choices were also made accordingly. No point wasting time and money on something that didn’t yield long-term benefits, no?

But by the 1950s, times were changing. Archaic rules were stomped out. Employment opportunities were greater. However, the problem was that young women didn’t see this coming. They still picked educational paths based on how things were in the past. They didn’t expect to have a long and active career. They underestimated how much they would and could work. And in a sense, that meant they weren’t really ready for the demands of the workforce.

That began to change only in the 1970s. Young women were living through the change. They began to take up more college-related preparatory courses in high school itself. Their math scores improved vastly. College attendance rates soared. They picked majors that men were studying. The median age of marriage shifted from 22 years to 25 years. A ‘quiet revolution’ was beginning.

And then came something else that helped boost female labour participation rates even further — the contraceptive or birth control pill. Suddenly, women were in more control of their bodies. That meant they could delay marriage. They could delay having a family. And instead, first, invest in their education and careers. Now sure, people kind of anecdotally knew this to be the case. But it was Goldin who actually did the research and proved the hypothesis. She’s the one who finally crunched the numbers to establish cause and effect.

So in many ways, Goldin basically made women front and center of her economics research. No one else had done it before.

But wait. There’s one more question here — why does a gender pay gap continue to persist? If everyone knows the history, shouldn’t it have disappeared by now?

Well, the thing is that these days the pay is actually similar straight out of college. But it begins to diverge once women have families.

Source: Nobel Prize website

And one theory that Goldin posits in her latest book is the rise of “greedy work”. Simply put, it’s the idea that employees who work long hours get rewarded disproportionately more than the extra productivity they eke out. Basically, if you double the working hours, it results in more than double the pay. And if you work half the hours, you get paid less than half.

Now the thing is, when women start families, inevitably, they’re the ones who end up with child-care duties! And the end result is that they don’t have time for this “greedy” work. So they get penalized a lot more if they cut back on hours. That could partly explain why the gender pay gap continues to persist.

But wait…why can’t families just split duties equally then, you say?

Well, Goldin also points out that there might be a problem that arises with such an arrangement too.

You see, once children come into the picture, someone does need to be “on-call” at home. They’ll need to be there for emergencies. And that person might need a more flexible schedule or a less demanding job. But if you choose a 50–50 split, it means that both parents will have to share the responsibility of being “on-call” at home. As a consequence, both will then need to take up a less demanding job to attain flexibility. And that can depress household earnings further. In Goldin’s words, “the 50–50 couple might be happier, but would be poorer.”

Interesting, isn’t it?

So yeah, to sum it up — Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Prize in Economics because she showed how important flexibility is to a woman’s earning potential.

How do you think this plays out in the Indian context? Tell us.

Until then…

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and X (formerly Twitter).

Note: Goldin’s research is focused on the US market and may not be entirely applicable to other countries such as India.

Ditto Insights

Do I need more than my corporate plan?

One of the most common questions that we keep getting is this — Is my corporate health insurance good enough?

And the answer is —a corporate insurance policy is a good place to start. For instance, they are relatively inexpensive. They may offer coverage for your ailing parents when retail policies may no longer offer coverage and there are no waiting periods with most corporate policies. So all diseases are covered from day 1.

But corporate policies have their own pitfalls. A good chunk of employers are simply trying to comply with regulations, offering their employees a bare minimum plan that just does the basics right. They may have restrictions that you didn’t conceive and they may not offer you the most robust protection.

Also, company coverage is great only so long as you’re working for the company. Should you leave the company or you’re forced out of the firm you may lose coverage. Now granted companies do offer you the provision to switch to a retail plan at the time, but this is incumbent on your current health condition. They can choose to deny your application.

So ideally you should consider buying an individual policy to supplement your protection. And for this, you can talk to our team at Ditto. We have a limited number of slots every day so make sure you talk to us at the earliest -

Just head to our website — Link here

- Click on “Chat with us”

2. Select “Health" or "Term Insurance"

3. Choose the date & time as per your convenience and RELAX!

Our advisors will take it from there!