Why Bengaluru has the most expensive metro

In today’s Finshots, we talk about why Bengaluru’s metro rail system is the most expensive in India, and why it’s about to get even more expensive.

But here’s a quick sidenote before we begin. In just a few days, GST on insurance premiums will be gone — making policies cheaper. And while most people will scramble to make sense of it, you can walk in prepared.

Join our 2-day masterclass where we break down health and life insurance in simple, actionable steps. You’ll know exactly what to buy, how much cover you should choose, and what traps to avoid.

👉🏽 Click here to reserve your spot today. Only 180 seats left — and this is your last chance to get clarity before the change.

Now, onto today’s story.

The Story

Back in February, I was on my usual commute to work. Nothing out of the ordinary. The auto driver picked me up on time, my lunch was packed and my metro card was recharged.

Everything was normal until I swiped my card at the exit gate and the charge was higher than I was used to. The BMRCL, Bengaluru’s metro authority, had hiked fares by almost 70%, and it immediately made them the most expensive metro in India.

And I wasn’t the only one feeling the pinch. Almost 10 lakh riders use the metro daily to get to work, school or simply to avoid the city’s traffic.

So yeah, what was once affordable and efficient had suddenly turned into an expensive routine. And for months, the public had been left wondering why their metro fares were so high.

Because you see, before any sort of fare revisions are made, they need to be approved by something called a Fare Fixation Committee (FFC), usually composed of a retired High Court judge, a few technical experts and representatives of both the central and state governments. Basically, they put their recommendations in a report on what the right fare hike should be for a metro rail system before it’s put into action.

But that didn’t happen here. Instead, the fare was hiked first, then the report came out seven months later i.e., last week, just a day before a High Court hearing on the lack of transparency around such steep prices.

And that’s not even the most shocking part. What’s even more shocking is what’s in the report. So what’s in it, you ask?

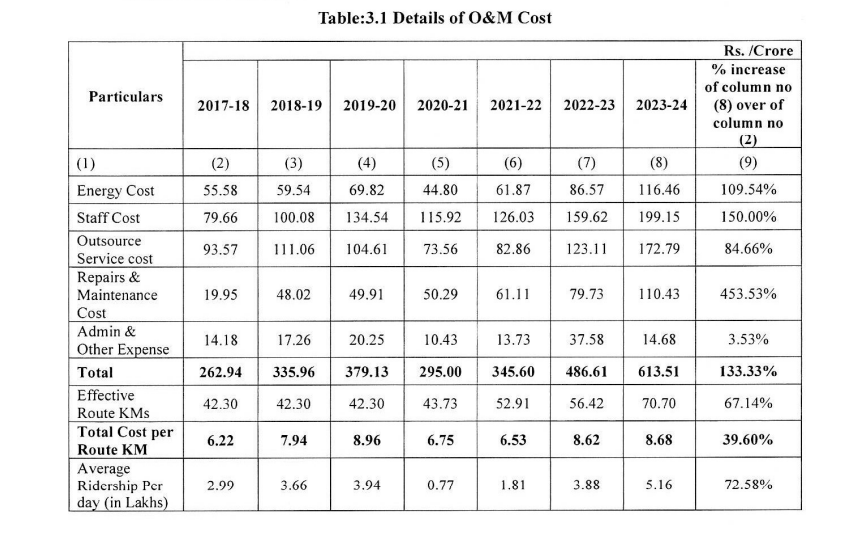

For starters, BMRCL argued that between 2017 and 2024, its expenses had exploded. Staff salaries, energy bills, outsourcing services, repairs, maintenance — everything, they claimed, had gone up. By their math, costs ballooned to ₹613 crores in 2024, a whopping 133% jump over 2017.

But here’s where the numbers stop adding up.

During the same period, Bengaluru’s metro network nearly doubled in size — from 42 km to 76 km. When you spread the spending across this larger network, the story changes. On a per-kilometre basis, actual expenses rose just 39% — from ₹6.2 crore per kilometre to ₹8.6 crore. That’s a huge gap compared to the 133% hike BMRCL keeps pointing to. In other words, it looks like the metro authority only looked at the headline costs, without accounting for the fact that the system itself had grown and absorbed much of the increase.

In fact, the Fare Fixation Committee (FFC) saw the same problem.

And there’s another angle. Even if costs rose by 39%, ridership had surged too — from around 3 lakh daily passengers in 2017 to nearly 5 lakh in 2024, a 72% jump. In simple terms, higher revenues were covering rising costs.

Despite this, BMRCL pushed for nearly double what the FFC recommended. The Committee, however, suggested a far more modest 51.5% fare hike spread out over 7.5 years, with a base fare of ₹10 — while BMRCL wanted to nudge it up to ₹21 (or from ₹60 to ₹123 if you were travelling long stretches, say 25 km).

But to be fair, you also have to cut BMRCL some slack, given the financial mess it finds itself in.

Take the Shadow Cash Support (SCS) from the state government. Since a metro is essentially public transport, the state chips in to keep it running. In BMRCL’s case, this has come in the form of reimbursements for cash losses and interest-free subordinate debt — money meant to help it repay loans taken from the Government of India and other lenders.

The problem? The state’s finances aren’t in the best shape. Which means this SCS lifeline may not last much longer. And if the state can’t keep up its share, the funding structure itself (usually a joint venture between state and central governments), starts to wobble.

Even outside the FFC report, both the Chief Minister and Deputy Chief Minister have admitted that 80–87% of recent funding came from the state government, with the centre contributing the rest. And that’s not even counting the bonds and loans raised separately.

So, if the state’s purse strings tighten, BMRCL has to look elsewhere for money. But where? Well, that’s where the next reason for a fare hike comes in.

Right now, the BMRCL has looming loans. Over the next five years, it must repay external loans worth ₹13,106 crores, plus subordinate debt of ₹21,521 crores. With numbers that massive, borrowing more isn’t really a way out, which tells you why fare hikes matter.

But then there are also the construction delays. Every time a metro project is pushed back, costs balloon and revenues are lost. Until a line is complete, it’s just a dead asset sitting on the books. A Moneycontrol report pointed out that the newly opened Yellow Line ended up costing ₹400 crores per kilometre — far above the usual ₹250 crores for an elevated line. Delays don’t just mean higher budgets; they mean missed ticket revenues and spiralling expenses too.

And finally, the network problem. Bengaluru boasts the longest metro in South India. But stack it against Delhi’s, and it looks tiny. Delhi Metro has a 394 km network with 289 stations, while Bengaluru’s, just 96 km as of now (and only 77 km when the fare revision was first proposed). The extra stretch came from the recently inaugurated Yellow Line.

A smaller network means fewer people to spread costs across. So even if ridership is at record highs, BMRCL still ends up squeezing more revenue out of every passenger.

So what’s the real takeaway from all this?

A public transport system is meant to make travel affordable, accessible, and to ease the burden of a traffic-choked city. But when the metro carries the tag of being the “most expensive” in India — with another hike already lined up for February next year, commuters could simply end up back on the roads.

The FFC report projects that by 2029–30, Bengaluru’s metro could see 15.8 lakh daily riders. But that number depends on fares staying reasonable. Keep pushing them up, and you risk driving people away instead of drawing them in.

Because the answer isn’t to slap on fare hikes year after year. That only weighs down commuters and defeats the very purpose of a public transport system.

Sure, higher fares might give BMRCL some short-term breathing room. But if tickets get too pricey, people will stop buying them.

What’s needed is a bigger rethink — restructuring BMRCL’s financial model, speeding up construction to avoid costly delays, and most importantly, learning from how other cities run their metros.

The FFC, in fact, studied examples from Delhi, Chennai, Singapore and Hong Kong. These systems didn’t just depend on ticket sales. They followed transparent, formula-based fare revisions and pulled in significant money from outside sources. Think advertising, real estate development, and even event tie-ups. Bengaluru’s metro has to head in the same direction if it wants to stay sustainable and commuter friendly.

Because at the end of the day, there’s no shortage of people who want to use the metro. And the last thing they should be worrying about is how much more their next ride is going to cost.

Until then…

If this story helped answer the questions you’ve had about Namma Metro’s abnormal fare hikes, why not share it on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and X to help more people decode the mystery?