Why are Indians scared to invest in the stock market?

In today's Finshots, we have reviewed the SEBI Investor Survey 2025 and found out what causes some Indians to stay away from the stock market.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

Earlier this week, SEBI released a detailed investor survey on retail investor participation. And beneath all the charts, tables, and segmentation, the regulator was circling around a deceptively simple question.

Why has investor awareness failed to convert into sustained participation, even after a decade of digital and regulatory reforms?

You see, the premise behind India’s market-building effort has been straightforward. If markets are made accessible, affordable, and safe, people will eventually participate. And over the years, SEBI has done much of the heavy lifting. Digital KYC reduced onboarding friction. Settlement cycles became faster. Broker norms were tightened. Disclosures improved. Grievance redressal systems were strengthened.

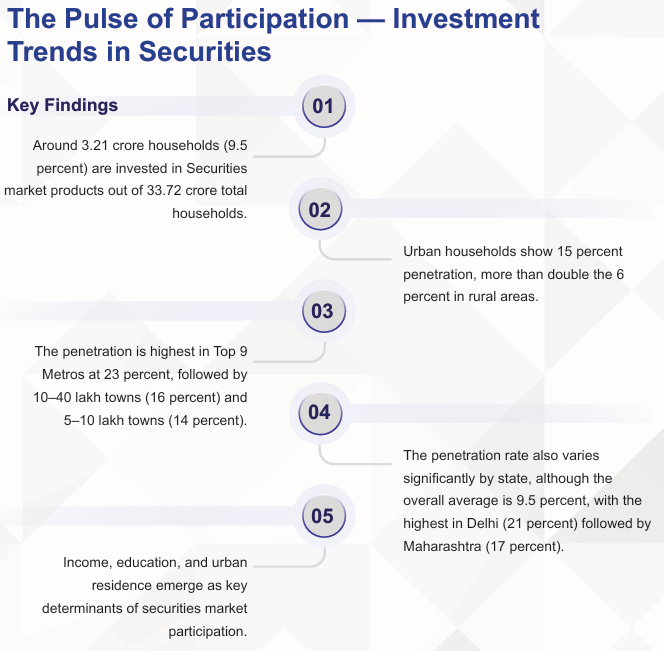

On paper, the foundations look solid. And yet, participation remains low. For context, SEBI’s survey found that only 9.5% of Indians actually invest despite 63% of them being aware of the stock market. That’s based on a sample of 90,000 Indian households.

To put this in perspective, roughly 55% of households in the US are directly invested in the stock market. In Vietnam, the number is around 16%.

But in India, the disconnect is stark. It’s more like people know markets exist. And many have even engaged briefly. But most either stay out or drift away after entering.

Why?

Well, that’s the puzzle SEBI is trying to solve.

For instance, take a look at this chart from the survey:

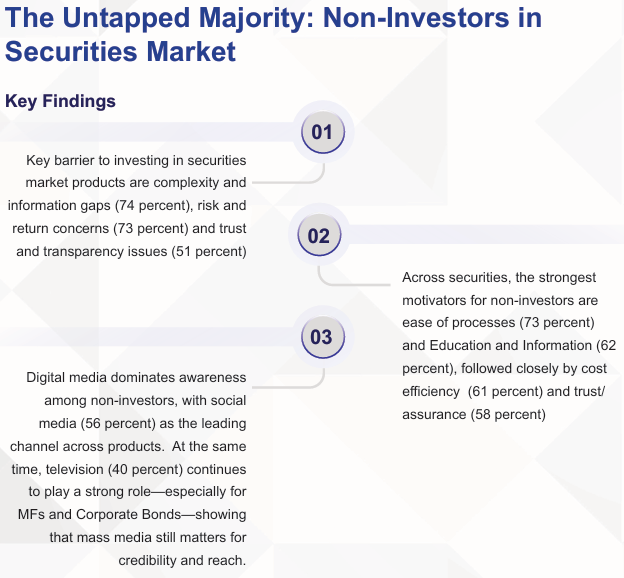

The instinctive explanation for this is fear. Indians are risk-averse. Markets are volatile. People prefer safety. There is some truth to this. But the survey points to a more uncomfortable explanation.

The biggest barriers are not access or even expected returns. They are complexity and confusion. Many households don’t feel equipped to navigate markets on their own. They don’t know how to start, whom to trust, or what “normal” behaviour looks like once money is invested. And when volatility shows up, as it inevitably does, the default response is to step back rather than stay invested.

In that sense, awareness hasn’t failed. Capability has.

And by capability, we mean what’s missing isn’t information, but the mental models, and decision frameworks that help people act under uncertainty and stay invested when outcomes don’t move as expected.

Now you’ll say that digital reforms made investing easier to enter the markets. Discount-brokerage apps such as Zerodha, Upstox & Groww replaced intermediaries. As a result, processes became faster, but reassurance thinned out to an extent.

And you’re right. But then you’d also agree that investors are now expected to make decisions continuously, interpret outcomes independently, and process a constant stream of information coming from apps, social media, and financial influencers.

For many people, this is overwhelming. And often unnecessary.

Over time, this cognitive overload runs into a deeper reality. As incomes rise, money stops being only about safety and starts being about progress. Better housing. Mobility. Education. Experiences. Freedom. But for a large section of the population, those goals increasingly feel out of reach through slow, conventional savings alone.

Which means that the markets get framed in two extreme ways. For some, the stock market stops looking like a normal place to save and grow money. It starts looking either like a shortcut to get ahead quickly or a gamble where getting one call wrong can set you back for years.

Sure, SEBI can regulate products, platforms, and intermediaries. But it cannot regulate how people perceive uncertainty, how they process losses, or how comfortable they feel with financial ambiguity.

That is why the gap persists. Even though people know that the markets exist, they don’t feel comfortable living with them.

Another interesting thing about the investor survey is that it challenges a long-held belief in Indian market policy. That building access and protection is enough to build participation. However, it isn't.

India’s stock market problem is not a lack of awareness. But a lack of confidence, clarity, and continuity. People need markets that feel navigable before they invest, understandable while they are invested, and survivable when things go wrong.

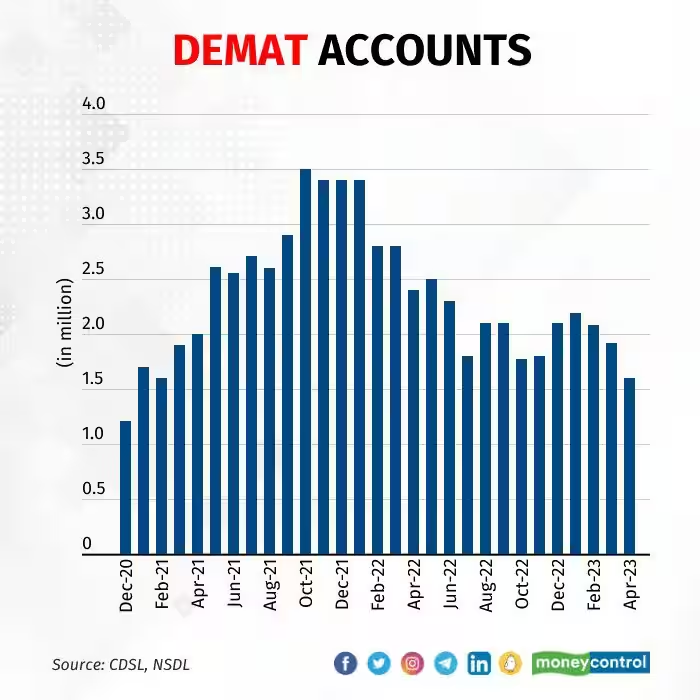

This also explains familiar patterns of why participation spikes briefly and then fades, such as what we saw right after COVID.

So if SEBI wants broader participation, investing shouldn’t feel like a second job that demands constant attention and decision-making. It should fit into everyday life, where people can invest, step away, and still feel confident that they are doing something reasonable.

So, what can we do about this?

Well, remember we referenced earlier that the participation of Americans in the stock market is 55%? That’s not an accident, and not because the US is a developed economy. At least not entirely.

A large share of this participation comes through retirement accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs (Individual Retirement Arrangements), rather than direct investing. For the uninitiated, a 401(k) is an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan where employees set aside a portion of their pay, usually with an employer match, into a retirement fund that’s automatically invested in diversified stock portfolios or mutual funds. And while 401(k) participation isn’t mandatory, automatic enrolment and tax incentives have made equity ownership the default for millions of workers. So if India wants to raise long-term market participation meaningfully, it will likely need a comparable retirement-linked investment framework, where investing happens by default rather than by choice.

Now, you might say, "Well, Finshots. We already have the EPF & NPS in India. Is that not equivalent to the 401k?"

Sure, but there are a few key differences.

Firstly, your EPF money doesn’t go directly into stocks. It’s invested in ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds or market-linked instruments) and mostly in government bonds and fixed securities. NPS, on the other hand, does invest a portion of your money in stocks. But that depends on your choice. You can aggressively allocate your NPS savings to equities or stay away from stock market exposure altogether.

Secondly, if you’re a salaried employee, you’re automatically enrolled in EPF. NPS is optional unless you’re part of the public sector. In contrast, in the US, employees are enrolled in a 401(k) by default and have to actively opt out if they don’t want it. You can also invest 100% of your contributions in the markets, tax-free.

That isn’t the case in India. Here, you usually have to opt in, and that extra friction makes investing that much harder.

Because until investing feels like something you are incentivised to do, awareness alone will keep hitting a ceiling.

And that’s the real takeaway from the survey.

Until next time…

If this story helped you learn something new, feel free to share it with your friends, family or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

Insurance Masterclass Series: Claims made Simple!

We’re hosting a free 2-day Insurance Masterclass where we’ll walk you through simple rules to pick the right insurance plan and the common mistakes you should avoid.

📅 Saturday, 24th Jan ⏰at 11:00 AM: Life Insurance

How to protect your family, choose the right cover amount, and understand what truly matters during a claim.

📅 Sunday, 25th Jan ⏰at 11:00 AM: Health Insurance

How hospitals process claims, common deductions, the mistakes buyers usually make, and how to choose a policy that won’t disappoint you when you need it most.

👉🏽 Click here to register while seats last.