Is a controversial subsidy scheme setting India's EV dreams on fire?

When a subsidy scheme for Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles (FAME) was rolled out in 2015, it aimed to subsidise production costs for EV makers and make EVs affordable for the masses. But in its second phase starting 2019, the scheme has become a magnet for controversies, sparking conflict in the EV world.

So in today’s Finshots we discuss the debate surrounding FAME II and see why it could be stalling India’s EV wagon.

The Story

Indian EV (electric vehicle) manufacturers have been in a tough spot over the last few months. At least a dozen of them including Okinawa Scooters are seeking out investors and trying to raise money, simply because they don’t seem to have enough cash to run day-to-day operations.

And they’re blaming an unusual factor for their woes ― an EV subsidy under a scheme called FAME II.

Wait! Aren’t subsidies supposed to help EV makers and ultimately buyers like you and me? Of course. And FAME II has been one of the most beneficial subsidies to the EV industry.

To put things in perspective, it helped dramatically lower E2W (electric two-wheeler) prices by about 35%. And in its fourth year (FY23), FAME II has been able to pull up overall EV sales by a whopping 153% over the previous year. Reaching 1.15 million units, which surpasses even the cumulative since 2019.

None of the earlier EV subsidies have been able to have an impact of that kind ever since their inception in 2015.

Then why has the subsidy scheme suddenly become the centre of attention for all the wrong reasons, you ask?

To understand that, you’ll need to know how FAME II works.

See, EV subsidies have a very simple goal ― price reduction. Since EV manufacturing is still in the nascent stage, making them doesn’t come cheap. So if the government wants to electrify 80% of two-wheelers and 30% of private cars on roads in India by 2030, it has to make them affordable.

That’s exactly why it came up with a pilot subsidy scheme worth ₹895 crores called FAME in 2015 to support private EVs. Four years later it rolled out the second phase that also spread its wings over public transport with an estimated cost of about ₹10,000 crores. Although their initial plan was to extend it over 3 years, FAME II continues to stay till FY24.

That way the subsidy would boost demand for over 15 lakh EVs that includes buses, two, three and four-wheelers.

And in order to reduce their costs through government subsidies, manufacturers had to comply with a few conditions. And eligible EV makers could pass on these subsidies to buyers even before the government credited the sum to their accounts.

It should have gone smoothly. But instead a lot of things seem to have gone wrong.

For starters, the EVs under question had to abide by localisation rules. This meant that as and when the government notified it, a certain percentage of vehicle parts had to be fetched locally. As of now, local EV makers must contribute to at least half of the value added, to claim FAME II subsidies.

Another important condition pertained to the the ex-factory price or the price at which the EV is sold before it reaches the road. The government prescribed upper limits for companies looking to avail subsidies. For instance, ₹1.5 lakhs for E2Ws, ₹5 lakhs for E3Ws, ₹15 lakhs for E4Ws and so on. If your vehicle breaches the limit then you can’t claim subsidies.

But a few months ago, the government received complaints about violations. Apparently EV makers were trying to claim subsidies after resorting to a few interesting tactics. Folks like Hero Electric and Okinawa Scooters are alleged to have quoted lower prices by separating the vehicle price from other things like software and chargers, which also happen to be key components of the vehicle. They are even alleged to have added minimal value after importing most parts from countries like China.

So, they were claiming FAME II subsidies despite flouting the conditions laid out by the government.

The result?

The government started sending out notices to look into alleged subsidy frauds. Their incentives were immediately blocked. And as of now nearly ₹1,500 crores worth of subsidies remain in limbo. The government hasn’t processed it for a year.

And remember? These folks had already sold vehicles at lower prices to customers. So without being compensated, they have no way to generate working capital. This has also hit their creditworthiness. And it has become increasingly hard to even borrow money.

But wait, why couldn’t they just follow the rules like everybody else? Why did they have to resort to these tricks?

Well, for one, the pandemic wasn’t good to anybody. So EV makers weren’t an exception. Supply chains were mostly tight and there was no way to straighten them out within the country. So we had to depend on imports. It was only later in 2022 that the government came up with incentives for subsidizing machinery that makes lithium cells. So it’s possible that companies could do very little to add value locally.

Another point of defence is that not all software is mandatory for EVs. So stuff like chargers and additional software wouldn’t be bundled if buyers didn’t want to purchase them.

But having said that the government will also have its own say here. You see, India’s charging infrastructure isn’t enough to plug and ride. According to data released in the Lok Sabha, there’s just 1 public charging station for every 393 electric vehicles in the country. And going by that, you won’t really have many customers tossing the idea of buying chargers along with their new EVs. So how can anyone make the argument that chargers aren’t essential components, huh?

Also you can’t really unbundle an EV from its software. So this argument is unlikely to hold a lot of water too.

And if this whole controversy blows out of proportion these companies could be in a lot of trouble. More importantly, it could affect the EV growth story of India. Starting over can be hard. So, perhaps the best thing to do right now is for the government and the EV makers to come to some sort of a compromise before things get out of hand.

Until then…

Also don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Twitter

A message from one of our customers

Nearly 83% of Indian millennials don't have term life insurance!!!

The reason?

Well, some think it's too expensive. Others haven't even heard of it. And the rest fear spam calls and the misselling of insurance products.

But a term policy is crucial for nearly every Indian household. When you buy a term insurance product, you pay a small fee every year to protect your downside.

And in the event of your passing, the insurance company pays out a large sum of money to your family or your loved ones. In fact, if you're young, you can get a policy with 1 Cr+ cover at a nominal premium of just 10k a year.

But who can you trust with buying a term plan?

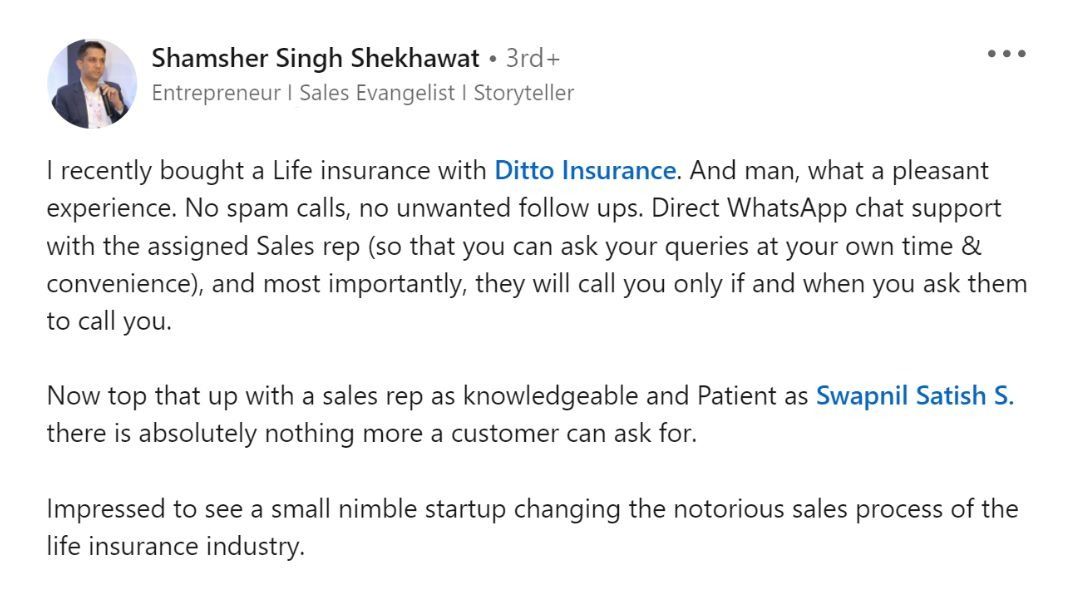

Well, Shamsher - the gentleman who left the above review- spoke to Ditto.

Ditto offered him:

- Spam-free advice

- 100% Free consultation

- Direct WhatsApp support for any urgent requirements

You too can talk to Ditto's advisors now, by clicking the link here