What's a smell trademark, anyway?

In today’s Finshots, we tell you how Japanese tyre-maker Sumitomo Rubber secured legal approval for a rose-scented tyre as a trademark — something no one had managed before in India. And why this unusual win could open the doors for a whole new category of sensory trademarks in the country.

But here’s a quick note before we begin. If you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

India’s perfume market is worth around ₹4,500 crore. And roughly ₹2,000 crore of that sits in the unorganised segment. So if you were to estimate how big the market for perfume dupes or copycat fragrances really is, even a conservative assumption that half the unorganised segment consists of dupes leaves you with a ₹500–1,000 crore shadow market built purely on imitation scents.

And the reason this parallel world thrives is because of one odd quirk in trademark law, not just in India, but in many parts of the world. You simply can’t trademark an intangible feature like smell or colour if that feature is the product itself.

A classic example is from the luxury perfume world. Chanel once tried to trademark the scent of “No. 5” in the UK, and the authorities rejected it. Simply because, in perfume, the scent is the product. You can’t separate one from the other.

It also explains why dupes are so common. If someone buys a Burberry fragrance and another person shows up wearing a ₹300 version that smells almost identical, Burberry can’t sue them for copying the fragrance. The smell alone can’t be protected unless the bottle or branding is also being faked.

But that’s just one part of the nuance around non-conventional trademarks in India. And in case you’re wondering what “non-conventional” even means, it’s basically a trademark that isn’t a word or logo but still identifies a brand through some experience of it like shape, sound, colour or even smell.

Now let’s come back to the nuance we were talking about. The Trade Marks Act defines a trademark as “a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include the shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours.”

This simply means two things. One, a trademark must be shown visually in a clear graphical form. And two, it must be distinctive enough for customers to recognise where the product comes from.

And this is exactly why smell trademarks have never taken off in India. First, smell is invisible. You can’t photograph it, draw it or attach it neatly to your application form. Which is why, for decades, people believed it was impossible to register an olfactory trademark in India. Second, some scents serve a functional purpose, which immediately disqualifies them. Take Fevicol. You can identify Fevicol by its fragrance, sure, but the company can’t trademark it because the scent is added to mask the adhesive’s natural odour. It improves the user experience, and according to law, anything functional can’t be trademarked.

But then, a few days ago, one Japanese company, Sumitomo Rubber Industries, the folks behind Dunlop Tyres, managed something no one else in India had. It actually got legal approval for a rose-scented tyre as a trademark.

Okay, we know that sounds a little bizarre. Who goes around smelling tyres, right? But we’ll come back to that. First, let’s see how Sumitomo even pulled this off.

The story really begins with the biggest hurdle in trademark law — graphical representation.

Sumitomo has been selling tyres with a floral fragrance for decades and wanted India to officially recognise that the scent belonged to them. But when they applied in 2023, the Trademark Registry rejected it on two grounds. One, the rose scent wasn’t distinctive enough to act as a trademark. And two, they hadn’t provided an acceptable graphical representation of the smell.

Instead of backing off, Sumitomo went back to rework its application. They refined their arguments, and explored new ways to satisfy the law. And this eventually led to a critical shift: if the problem was visual representation, they needed science to turn the smell into something tangible on paper.

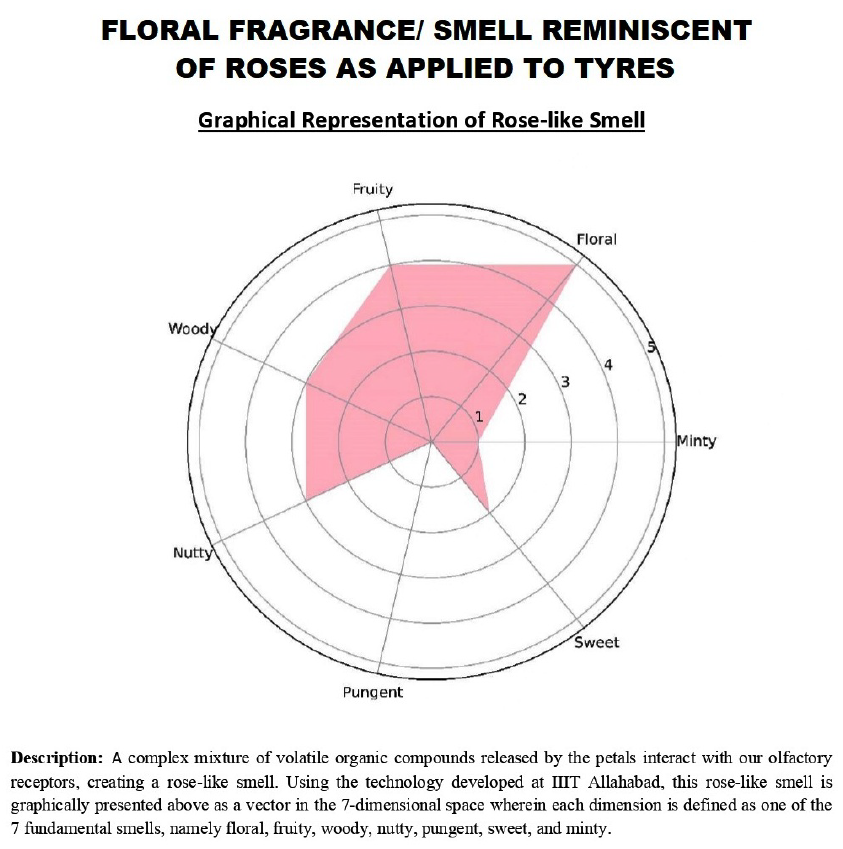

This is where the breakthrough came. The company teamed up with three scientists from IIIT Allahabad who created something called a seven-dimensional olfactory vector. In simple terms, they analysed the rose fragrance and broke it down into seven measurable scent profiles — floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet and minty. Each was given a numerical value based on how strongly it appeared in the scent. Once they had all the numbers, they plotted them on a graph.

Suddenly, the smell became a measurable, permanent “fingerprint” instead of something subjective floating in the air. The Registrar could now see the fragrance in a fixed, objective form.

The other major concern though, was distinctiveness. To prove that adding a rose scent to tyres isn’t functional in any way, Sumitomo argued that adding a floral scent to tyres doesn’t improve how they work. Tyres naturally smell like rubber, and a rose fragrance doesn’t make them more durable, efficient or safe. It simply acts as an identifier. And when someone unexpectedly smells roses from a passing vehicle, it creates an instant mental link with the brand. The Registrar found this convincing, especially because Sumitomo has been using this scent worldwide since 1995.

And since this was India’s first-ever smell trademark application, the Registry wanted to be absolutely certain before breaking new ground. So it looked at how countries like the UK, the US, Europe and Australia already recognise and handle smell trademarks.

There was also one more important legal point. India’s trademark law uses the word “includes” when defining what a mark is, not “consists only of.” That single word gives the law flexibility. It doesn’t limit trademarks to traditional forms. It leaves room for new ones, as long as they meet the existing conditions of graphical representation and distinctiveness. In other words, the law already allowed smell marks. Just that no one had cracked the representation problem until now.

So yeah, that’s how Sumitomo flipped the problem on its head, turned a smell into science, and paved the way for India to finally register its first-ever smell trademark.

But while that chapter closes, the story doesn’t end, because you’re probably wondering what a tyre company plans to do with a rose-scented trademark. How exactly does this help it sell more tyres?

After all, most of us only smell tyres if we’re mechanics changing them or, in this rare case, if a rose-scented one happens to roll past us. And when people buy cars, they don’t really get to pick the tyres anyway. Sure, you can customise them, but who’s paying a premium for scented tyres? Unless a tyre improves operational efficiency, most buyers won’t bother swapping the default ones. Even carmakers have their own long-standing supply arrangements with tyre manufacturers, and a fragrance is hardly going to influence those deals.

So why do this at all, you ask?

Well, maybe Sumitomo is thinking way ahead. Imagine a world of driverless cars where the cabin experience becomes as important as the ride itself. In that future, even the ambient scent of tyres could add to the overall feel of the vehicle instead of relying solely on in-cabin perfumes. And securing the smell trademark today ensures competitors can’t use the same olfactory signature tomorrow.

In the present, though, this move probably serves another purpose. It signals to investors that Sumitomo is experimenting with brand protection in fresh, non-traditional ways. And that kind of innovation always gets noticed. But one thing you can’t ignore is that it opens the door to an entirely new set of possibilities in smell trademarking, even for categories like fragrances. Who knows, maybe soon a luxury hotel chain will trademark a signature lobby scent to protect the ambience it’s known for.

And watching how these new possibilities unfold is going to be quite interesting.

Until then…

Liked this story? Share it with your friends, family or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and X.

How Strong Is Your Financial Plan?

You've likely ticked off mutual funds, savings, and maybe even a side hustle. But if Life Insurance isn't a part of it, your financial pyramid isn't as secure as you think.

Life insurance is the crucial base that holds all your wealth together. It ensures that your family stays financially protected when something unpredictable happens.

If you’re unsure where to begin, Ditto's IRDAI-Certified insurance advisors can help. Book a FREE 30-minute consultation and get honest, unbiased advice. No spam, no pressure.