What is going on at Ola Electric?

In today’s Finshots, we take a look at why Bhavish Aggarwal has been continuously selling his stake in Ola Electric, and why that may or may not be cause for concern.

But here’s a quick side note before we begin. Trust Finshots for Finance? You’ll love Ditto for insurance.

Built by the same four friends behind Finshots, Ditto is here to make insurance simple. No spam, only honest advice to help people make smart insurance decisions.

✅Backed by Zerodha

✅Rated 4.9 on Google (13,000+ reviews)

✅7 lakh+ customers advised

Click here to talk to an IRDAI-Certified advisor for FREE.

Now on to today’s story.

The Story

Every EV boom needs a hero story. In the US, it was Tesla, the company that bled cash for years before scale flipped the switch. In China, it was BYD that mastered vertical integration by building batteries, controlling supply chains, and waiting for policy alignment and demand.

And in India, that company is Ola Electric. Or is it?

You see, it was one of the few Indian startups willing to bet big on manufacturing instead of playing it safe as an assembler or importer. While most players focused on incremental launches, Ola tried to compress an entire EV playbook into a few years: building a massive factory in Tamil Nadu, localising production, and targeting the segment that actually matters in India, mass market two-wheelers. That focus gave it instant scale and visibility in a country where scooters dominate personal mobility.

Ola also understood branding and speed better than most incumbents. It packaged EVs as aspirational consumer tech rather than just transport, leaning heavily on design, connected features, and aggressive pricing to pull buyers away from petrol alternatives.

This, combined with direct-to-consumer sales and high-decibel launches, helped Ola build mindshare far faster than legacy manufacturers who were still testing the waters. It did what startups are supposed to do: move fast, push boundaries, and force the entire industry to accelerate.

In many ways, it was like Tesla and BYD, and that is what Aggarwal wanted to achieve with Ola Electric. But here’s the thing. Tesla’s toughest phase was not when they were losing money. It was when demand shot up, and they had to prove that ambition could translate into operational discipline, product reliability, and sustainable margins.

That is exactly the phase Ola Electric has entered now. And that is why the recent share sales by its founder, combined with mounting execution challenges, have suddenly become such a big talking point.

Before we get into what’s going on, here’s a bit of context:

Ola Electric was once the poster child of India’s EV ambitions. Backed by SoftBank, it promised scale, speed, and vertical integration. They built gigafactories and made everything, such as batteries and software, in-house. Scooters rolled out at breakneck pace over the last two years, and for a while, that momentum translated into rapid topline growth.

Even financially, the growth looks impressive at first glance. Ola Electric saw revenues climb from about ₹400 crore in FY22 to about ₹2,600 crore in FY23, and then to roughly ₹4,500 crore in FY25. Few manufacturing startups scale revenue that fast.

But the cost of that growth has been steep. Losses have widened alongside scale. Ola Electric posted a net loss of around ₹1,470 crore in FY23, which increased to ₹2,200 crore in FY25 (and is already at a loss of ₹2,280 crore this year).

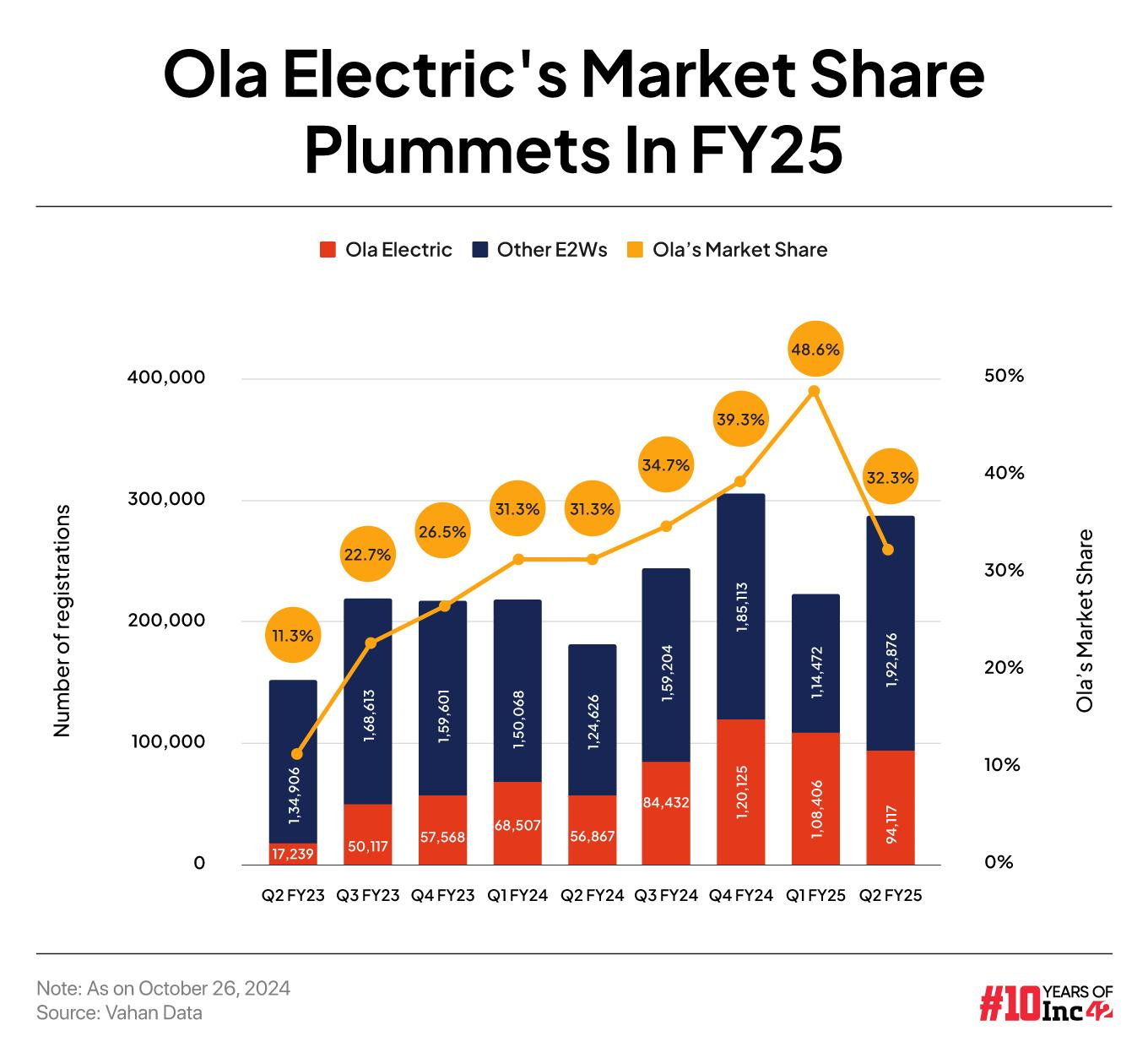

And since its IPO, the narrative has shifted further. Founder Bhavish Aggarwal has been steadily selling shares as the company faces operational issues and customer complaints. Add to this the competition from TVS, Bajaj, and Ather, which has only been intensifying, and we begin to ask ourselves why?

At its core, Ola Electric runs a capital-heavy, execution-sensitive manufacturing business. It sells scooters at thin margins to grab market share, hoping that scale, software, financing, and eventually batteries will turn losses into profits later. It’s the classic loss-leader strategy that worked for many tech platforms. However, Ola Electric is not a tech company pretending to be a manufacturer. It’s a manufacturer trying to behave like a tech company. Which, in a way, is good for a country that is starved of manufacturing startups. However, it does come with its own problems.

Let us explain.

Manufacturing does not reward speed the same way software does. In an app, bugs can be fixed easily. However, in a factory, defects ship to customers. And once they do, the costs show up everywhere, all at once: warranty provisions rise, service centres clog up, logistics costs spike, and brand trust erodes faster than any marketing campaign can fix.

The same problem showed up on the retail side. Last year, Ola expanded its physical footprint at breakneck speed, ramping up its stores from roughly 800 to 4,000 in a short span. But in regulatory disclosures soon after, the company admitted it did not have clear visibility on how much inventory sat at each store.

This is exactly where Ola has been feeling the strain. Rapid scale exposed weak links in the quality control and after-sales service of their vehicles. Complaints about scooter breakdowns, battery issues, and long service wait times eventually translate into financial problems, where each repair or replacement eats into margins that were already thin to begin with.

Now let’s talk about subsidies. For much of Ola’s growth phase, EV adoption was supported by generous incentives under the FAME scheme. Those subsidies helped keep sticker prices low and volumes high. But as FAME incentives have been tapered, the unit economics have tightened. When subsidies fall, either prices go up, or margins get squeezed. And in a hyper-competitive market, raising prices is risky.

Then, there’s competition. Back in the day, TVS and Bajaj never experimented with new products. So, the likes of Ola and Ather were safe. However, legacy brands have caught up with EV product quality, battery reliability, and software features.

Especially Bajaj Auto, whose EV segment is one of the few that is EBITDA-positive. This essentially means that they’re not bleeding money by selling more scooters.

And more importantly, the legacy two-wheeler companies already have dense service networks. For a customer buying a vehicle, that matters far more than an app or a flashy launch event. On that front, Ola is still building that network, which means higher costs today for benefits that arrive much later.

This is where the vertical integration bet cuts both ways. Building batteries, software, and manufacturing in-house gives control, but it also front-loads capital expenditure. Depreciation, employee costs, R&D, and factory overheads hit the P&L long before volumes are high enough to absorb them. The entire model depends on scale arriving fast and staying there. Any slowdown turns fixed costs into a drag.

And this brings us back to Bhavish Aggarwal’s share sales.

You see, founders sell shares all the time for various reasons: Liquidity, diversification, tax planning, etc. None of that is unusual. What makes this uncomfortable is timing. While the company said that his sale is to repay a promoter-level loan, rather than any intention to exit the company, Ola Electric is still loss-making, and cash burn remains high. There is also no clear inflection point yet at which losses start narrowing meaningfully despite revenue growth. When a founder reduces exposure in this phase, markets naturally wonder whether the most challenging part of the journey is still ahead.

There is also a personal angle. Ola Electric represents a large chunk of Bhavish Aggarwal’s net worth. Selling some stake converts paper wealth into liquidity without changing day-to-day control. From an individual risk perspective, that is rational. From a public market perspective, it weakens the alignment signal investors look for in capital-intensive businesses that need patience and long-term conviction.

Adding another layer of uncertainty is Ola’s recent pivot into adjacent products such as inverters and energy solutions. On paper, this looks like a sensible attempt to improve factory utilisation as scooter demand softens.

But in practice, it raises questions. Are these higher-margin extensions of the core business, or stopgap measures to spread fixed costs thinner? The answer will matter for both margins and focus.

So what’s really going on at Ola Electric is not a collapse. And it is not a scam. At least, we hope not.

It is something far more mundane and far more difficult: a company hitting the hardest phase of its lifecycle. The phase where vision has to give way to execution discipline. Where scale has to start producing profits, not just headlines.

Ola tried to build a manufacturing giant at startup speed. That audacity forced the entire industry to move faster. But manufacturing is unforgiving, and the margin for error is thin. And public markets are far less patient than venture capital, as we’ve explained here.

The next chapter for Ola Electric will not be defined by how bold its plans are, but by whether its profits start turning in the right direction. If that happens, today’s share sales will be forgotten. If it does not, they will be remembered as the moment the market realised that ambition alone is not enough.

And that, more than anything else, is what is really going on.

If this story helped you understand Ola’s business better or why Bhavish Aggarwal sold his stake, feel free to share it with your friends, family, and colleagues on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, or X. And tell them to subscribe to Finshots too.