President Trump dislikes quarterly results now?

In today’s Finshots, we talk about why US President Donald Trump wants public companies to stop reporting quarterly results.

But here’s a quick sidenote before we begin. We’re gathering real reviews for Health & Term Insurance policies to feature on the Ditto Insurance website, and we’d love your help! It’ll only take a minute or two:

• Click here for Health Insurance

• Or here for Term Insurance

P.S. Your review might just make it to our policy pages.

Thanks for helping us out!

Now, onto today’s story.

The Story

Trump loves making headlines. And this week, he’s been in the news so much that we couldn’t resist doing another story about him or rather about his issue with companies having to file quarterly earnings reports.

Now, if you’ve ever wondered what these reports are, think of them as a business’ report card that comes out every three months. They’re not fully audited, but they give a pretty clear snapshot of sales, expenses, profits and even cash flow. Investors and analysts rely on them to see how a company’s doing, compare results with previous quarters, and decide where to put their money. In short, these reports can move share prices, shape investment strategies, and even guide management decisions.

But here’s a fun fact. Quarterly results weren’t always a thing. Until 1970, American companies only had to report twice a year. They would submit an annual report called Form 10-K, which contained audited numbers, and a semi-annual update. That’s it. Then the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), the US’ market regulator, decided that companies should share updates more often, for the sake of transparency.

And things got even stricter after the early 2000s corporate scandals. Remember Enron? That’s when the US Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (in 2002). It made CEOs and CFOs personally sign off on financial statements, including the quarterly Form 10-Q, to reassure investors that the numbers weren’t cooked.

Trump, however, isn’t a fan of all this. He argues that the process is expensive and that it pushes managers to obsess over short-term results rather than long-term growth. So his quick fix is to scrap the quarterly ritual and go back to semi-annual reporting instead.

And honestly, Trump’s point might not be entirely off the mark.

You see, preparing quarterly results is no easy feat. Companies can spend nearly a month and a half just putting the numbers together, which means that by the time they’re done, they’re already halfway into the next quarter. Add to that the endless cycle of earnings calls (those conference calls where a company’s management walks analysts, investors, and the media through its results), updating guidance (basically telling investors what profits and revenues to expect next), and media appearances. For small listed firms, all this compliance chews up around 853 hours and a hefty chunk of money every year. Time and money that could probably be better spent actually running the business, or investing in projects that pay off in the long run.

And then there’s the bigger issue of ‘short-termism’. When companies report every quarter, managers often start chasing short-term targets at the expense of long-term strategy. Why? Because in those earnings calls, they set guidance for the next quarter. If they miss those expectations, the stock price can take a hit. Investors could panic and managers could lose out on bonuses tied to those targets. So they end up doing whatever it takes to hit the numbers, even if it’s not great for the company down the road.

For instance, in the pharmaceutical industry, a company might cut back on R&D (research and development) spending right before results to make profits look better. Sure, that keeps investors and analysts happy in the short run. But it also means fewer new drugs in the pipeline, weaker patents, and lost market share in the future. And that can be a risky approach.

But while these are the practical reasons why Trump thinks companies should stop quarterly earnings reporting, the real reason might be something else — the fact that the number of publicly traded companies in the US has been shrinking dramatically. To put things in perspective, back in 1996, there were nearly 8,090 of them. But that number dropped to 3,952 by the end of 2024. Even the Wilshire 5000 index, which was supposed to track all American stocks actively traded in the US, when it launched in 1974, now has only about 3,600.

If you’re wondering why, well, part of it is consolidation or big companies acquiring smaller ones. But another big factor is regulation. Laws like Sarbanes-Oxley and the rising cost of compliance have made life harder for smaller firms. And that meant many chose to delist, while others simply avoided going public in the first place.

And that’s where Trump steps in. He wants to reverse this trend by encouraging more companies, especially startups and small firms, to list on public markets. His pitch is simple. Smaller publicly listed companies create jobs, attract capital, and boost economic growth. The more of them, the better.

So, in his view, one way to make public markets more attractive is to ditch quarterly reporting, cut down compliance costs, ease the regulatory burden, and free companies from the constant treadmill of short-term targets.

But then this isn’t the first time that Trump has floated such an idea. During his first term in 2018, he even asked the SEC to explore whether companies could switch from quarterly updates to half-yearly ones. But back then, the SEC didn’t think it was a good idea.

And that’s probably because it saw a few problems with reducing the frequency of earnings reports.

To begin with, fewer reports might ease compliance pressure for companies, but it’s not great for investors. Just think about it. The longer the gap between reports, the less information outsiders have compared to insiders like employees, managers and executives. That creates what’s called “information asymmetry”. And it gives insiders a bigger window or an extra three months, to exploit private knowledge, trade stocks, or profit unfairly. Over time, that erodes investor trust. Less trust means less capital flowing into companies. Less transparency means more uncertainty. And uncertainty usually pushes share prices down.

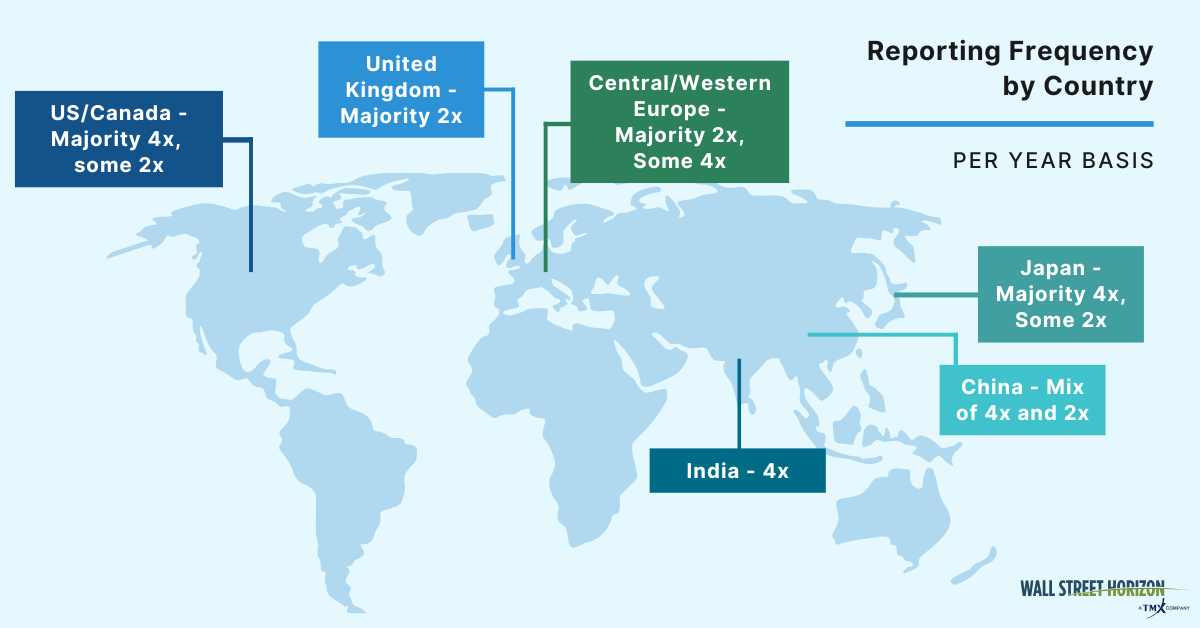

The SEC also had another case study to look at — the UK. Because the US isn’t the only country that’s thinking about moving to semi-annual earnings reporting. There are other countries that already do this.

The UK, for example, introduced mandatory quarterly reporting in 2007. But a Columbia study later found that the move didn’t really change how firms invested. Long-term spending on R&D, capital projects, and other growth initiatives stayed the same. And when the UK regulator rolled back the rule in 2014, expecting companies to suddenly invest more, that didn’t happen either.

On the flip side, something even more interesting happened. Even without the rule, most UK companies, over 90%, kept reporting quarterly anyway, because they didn’t want investors to think that they were hiding something. But those that stopped quarterly updates found themselves fading into the background. Analysts stopped covering them, and visibility dropped. And in the markets, out of sight often means out of mind.

And then there’s the question of cost savings. Sure, companies do spend time and money preparing quarterly reports. But studies suggest the actual savings from scrapping them would be modest — about $330,000 a year in legal and compliance costs for a small firm, which is just 0.2% of median revenues. That’s hardly a game-changer.

Put all this together, and you’ll see why reporting quarterly or semi-annually doesn't really change long-term business decisions. What it does affect, however, is how visible you are to investors.

And maybe that’s why the SEC, back in 2018, wasn’t buying Trump’s argument. Because if the UK is anything to go by, fewer reports don’t necessarily mean stronger markets or more listings. In fact, even with semi-annual reporting, the UK still struggles to attract fresh IPOs, or to hold on to the companies it already has. The proof is in the pudding. Fundraising from London IPOs in the first half of 2025 dropped to its lowest level since 1995. Only five companies made their market debut in those six months, raising a total of just £160 million.

So yeah, maybe this is something the Trump administration shouldn’t overlook, especially now that it’s asked the SEC to make this proposal a priority. If anything, it might want to scrap quarterly earnings guidance instead. Because that’s the real villain pushing companies to chase short-term results. But ditching quarterly results altogether, could be like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And if, in the quest to Make America Great Again, things go sideways, well… it could get very messy. And that would be… ‘Not good!!!’.

Until then…

If this story helped you understand Trump’s psychology behind scrapping quarterly results and you learnt something new, why not share it with your friends, family, or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, or X? After all, it’s always nicer to have a smarter bunch of folks around you.