The world’s running out of natural rubber. How can India solve this?

In today’s Finshots, we follow a humble tree sap from plantation to tyre, and ask why a material we barely notice could become the next strategic squeeze point like oil or semiconductors.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

Every time you ride a scooter, cross a bridge, or slip on a surgical glove, you’re depending on a drop of white sap tapped from a tree in Southeast Asia. It isn’t glamorous like oil or semiconductors, but natural rubber quietly underpins everything from tyres, conveyor belts, and even healthcare supplies. And the world is running short of it.

The global demand for natural rubber is on track to outstrip supply for the fifth straight year. The Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries (ANRPC), often described as the OPEC of rubber, has already warned that output growth is stagnating even as consumption keeps climbing.

But this isn’t something we can solve immediately.

You see, the problem is rooted in biology. Rubber trees take six to seven years before they can be harvested. So, we can’t immediately increase supply when demand rises. For much of the last decade, prices were so low that farmers abandoned plantations for more lucrative crops, and that gap is now starting to widen.

That wouldn’t be such a big deal if production were spread around the world. The risk could have been distributed so that it wouldn’t create as much of a shock. However, more than 75% of natural rubber comes from Southeast Asia. Mainly Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia. That geographical concentration makes the entire industry one fungus or cyclone away from a meltdown.

And currently, a leaf disease called Pestalotiopsis is already hurting Indonesian plantations by reducing yields by almost half. If it mutates or spreads across borders, global inventories could thin quickly. Add in the erratic rainfall and heat spikes of climate change, and the risks only multiply.

Expanding plantations by clearing more land sounds like an easy fix, except it runs straight into deforestation rules and public pressure. And you also end up with the classic monoculture and a more concentrated supply, which, again, is not good.

So yeah, it’s a tough industry for customers as well as suppliers.

Which makes us ask, where does India stand amongst all this?

In 2023–24, India’s rubber output was around 0.86 million tonnes against a consumption of 1.42 million tonnes. That leaves us importing nearly 40% of what we need, even as tyre makers are having a moment with exports topping ₹25,000 crore in FY25.

A global squeeze flows straight into domestic costs. And this isn’t some distant concern. If you build cars, trucks, roads, bridges, or medical devices, chances are rubber sits somewhere in your bill of materials.

Now you’re probably wondering: If rubber is so important, why can’t we just use a synthetic version of it? After all, it’s made from petroleum and is widely available.

Well, it’s not like we haven’t tried it. Synthetic rubber is a major component of car tyres, footwear, washers, etc. But natural rubber still wins on resilience, elasticity, and heat dispersion.

Aircraft tyres that face brutal take-off loads, truck tyres that run hot for hours, conveyor belts in steel plants, seismic bearings under bridges, surgical gloves, catheters, condoms – for many of these, synthetics are not good enough or become too expensive once you engineer around their shortcomings.

This is why the stakes go far beyond consumer goods. Rubber underwrites supply chains, defence readiness, and public health.

In fact, during the Second World War, the fall of Southeast Asian plantations to the Japanese nearly paralysed the Allies until they fast-tracked synthetic rubber programmes.

A modern shortage may not play out the same way, but it would rhyme. Countries will rethink sourcing, build buffers, and start treating rubber as a strategic resource rather than just another agricultural commodity.

So, how can we come out ahead? Because for India, this risk is exactly what presents an opening.

Southeast Asia will remain the core producer because the trees are already there. But India can carve out a profitable niche. And a quiet shift is happening in the North-East. Tripura, Assam, and Meghalaya now contribute about 17% of domestic rubber output, up from just 7.8% a decade ago. The land is less congested, and new logistics corridors are enabling the region to be part of the national supply chain.

And from late 2025, the European Union’s anti-deforestation rules (EUDR) will require plot-level traceability for rubber imports. At first glance, that looks like a headache. However, in practice, it could be a premium.

Because buyers in Europe, whether tyre or medical latex makers, will pay more for clean paperwork than risk regulatory penalties. But you can’t fake it. You need geo-tagged plots, a digital chain-of-custody, and clear audit trails.

All of this is what the Indian government is also working towards. The Rubber Board has launched geospatial mapping, traceability tools, and the BSNR platform to streamline compliance. The prize goes to whoever can scale quality and compliance fastest, and not just by planting more trees.

That means the play for India is not to chase acreage alone, but to own more of the value chain. Expansion in the North-East can happen even on degraded land through agroforestry, supported by survival-linked subsidies that pay out over several years rather than one-time grants. New disease- and heat-resistant clones need to move from labs to nurseries to farms with proper extension support. Better tapping/harvesting techniques can turn each tree into a more productive asset. And small landholders need access to steady working capital, so they aren’t forced to dump latex at a discount just to meet cash flow.

The next step is to climb the ladder in processing. More technically specified rubber, more medical-grade latex, more specialised tyre and non-tyre components, and a stronger reclaimed rubber industry that turns scrap into feedstock. Not to mention that India is already one of the largest dumping grounds for used tyres from around the world, which means the raw material for recycling is literally landing at our ports. And this is only going to increase: The reclaimed rubber market was about $278 million in 2023 and could grow to $1.2 billion by 2035.

It’s not glamorous work, but it reduces import dependence and cushions volatility. It also reduces waste. Every tonne of reclaimed rubber that replaces a virgin supply is one tonne less exposed to global shocks.

And finally, compliance itself can become a selling point. An EU-ready traceability backbone that geo-tags plots, logs harvest data, and ties shipments into digital custody chains can make Indian exports look very different from others. Once a few exporters start earning a premium for clean lots, the practice will spread, and the same rails can also reassure domestic buyers who deal with global clients.

India can be the steady, transparent, higher-value ecosystem that tyre makers and healthcare suppliers turn to when the world is tight. Even if we still import raw material, we can monetise the squeeze by moving up the chain. Over time, our import share may fall, but our premium share of value can rise faster.

Because at the end of the day, the world really is running short of natural rubber. Biology is slow, the weather is noisy, and the supply is concentrated. India can profit, but only if we play the long game on quality and compliance rather than the short game on acreage.

Until then…

Don’t forget to share it on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

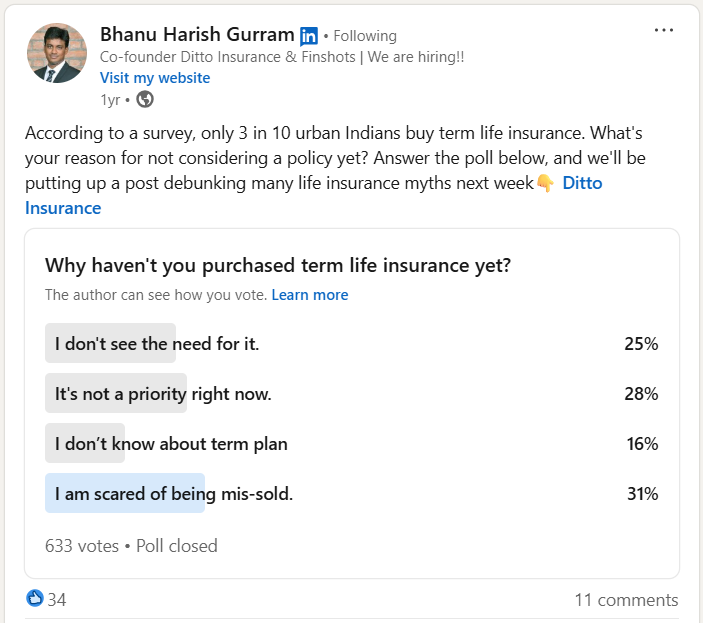

Our Co-founder Asked People Why They Avoid Term Insurance. The Top Reason? Right Here. 👇

31% said their biggest fear is being mis-sold. Many worry that agents may push costly plans or add confusing extras without full transparency.

That's a valid concern. After all, how can you trust something you don’t completely understand?

That’s why Ditto, a product of Finshots, has pioneered India’s #1 Spam-Free insurance platform. Our IRDAI-Certified advisors offer honest advice and help you find the right plan. Book a FREE consultation today.