The paradox of India's healthy finances

In today’s Finshots, we look at why India’s public finances begin to look riskier when you look at the states’ accounts.

But before we begin, if you love keeping up with the buzz in business and finance, make sure to subscribe and join the Finshots club, loved by over 5 lakh readers.

Already a subscriber or reading this on the app? You’re all set. Go ahead and enjoy the story!

The Story

Hey folks!

It’s been a few days since the Economic Survey and the Budget dropped. But we’re still kind of in that post-Budget hangover. Because even though we did explainers on both, there were a lot of interesting bits that didn’t quite make the cut. Today’s story is one of them.

You might remember us saying that India’s fiscal story looks pretty solid for an emerging market that lived through a pandemic and a series of external shocks.

And the numbers back that up. The centre has brought its fiscal deficit down from 9.2% of GDP in FY21 to 4.8% in FY25, and it’s aiming for 4.4% in FY26. At the same time, capital expenditure has steadily gone up. Between FY20 and FY25, the share of capital spending in total central expenditure rose from 12.5% to 22.6%, while effective capex climbed from 2.6% to 4% of GDP. In simple terms, the government tightened its belt without pulling the plug on infrastructure spending. And that’s a good sign.

Rating agencies have noticed too. In 2025 alone, India got three sovereign credit rating upgrades — one from Morningstar DBRS in May, another from S&P Global in August, and a third from Japan’s Rating and Investment Information, Inc. in September. That confidence has spilled over into the bond market as well. The spread between India’s 10-year bonds and US Treasuries has more than halved to about 2.5% by the end of 2025 compared to 2018.

For the uninitiated, spread is just the extra interest India has to pay to borrow compared to the US. The US 10-year Treasury is treated as the world’s safest borrower, or the “risk-free” benchmark. And India’s 10-year bond yield shows what it costs India to borrow for 10 years. So the difference between the two is the spread.

Which means that if US bonds yield 4% and India’s yield 6.5%, the spread is 2.5%. That extra 2.5% is what investors demand for taking on India’s additional risk. And when the spread narrows, it means investors see India as less risky and are more comfortable lending to it.

So yeah, the government has a lot to flaunt. India looks like a rare large economy that’s cutting deficits, investing aggressively, and still promising a sub-4.5% fiscal deficit by FY26.

But that’s only half the story.

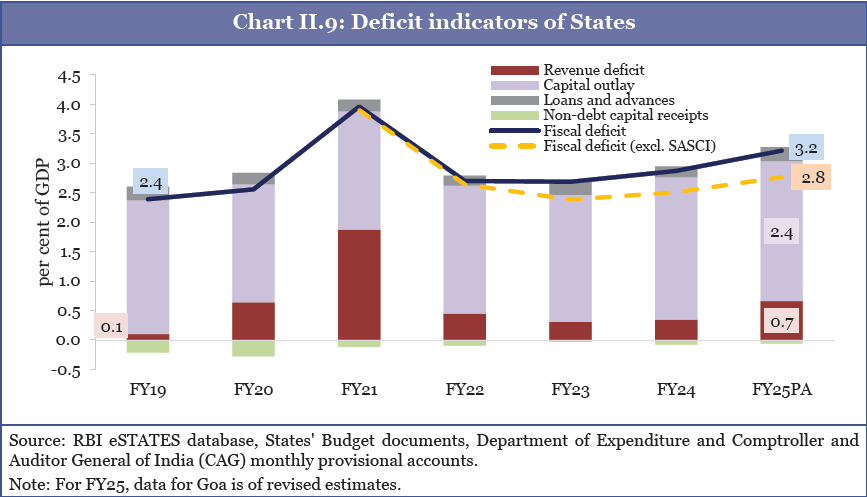

Because if you look at the section on State finances in the Economic Survey, things look fine on the surface. State fiscal deficits appear contained at about 3.2% of GDP in FY25. And if you subtract the impact of the centre’s 50-year interest-free loans to states under something called the Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment (SASCI), the underlying deficit comes down further to 2.8%. That sounds great… until you look at the composition.

Back in FY19, states as a group were running an almost balanced revenue account, with a deficit of just 0.1% of GDP. But by FY25, that had widened nearly 7x to 0.7% of GDP, with the revenue balance deteriorating in 18 states. To put that in perspective, 10 states slipped into a revenue deficit from a revenue surplus, 5 saw their revenue deficits worsen, and only 3 managed to stay in surplus, despite a deterioration.

The end result was that between FY24 and FY25 alone, the revenue deficit jumped by 0.4% of GDP, even as the centre was busy compressing its own revenue spending.

And why did that happen?

Well, to be fair, states’ own tax revenues have grown at a healthy pace post-pandemic at about 12.6% a year. Their share in total revenue has also risen to nearly 50%. So it’s not as if money isn’t coming in.

The problem though is that spending is growing even faster, and kind of in the wrong places. Many states have ramped up direct cash payments, especially women-focused income support schemes.

Now, we know this can sound like a controversial point. Welfare schemes are important. But the trouble starts when states end up spending almost all the income they earn on similar cash schemes and incentives, leaving very little room for basics like roads, schools, and hospitals. That’s not us saying this but data coming straight from the Economic Survey.

Aggregate spending on UCT (Unconditional Cash Transfers or direct cash payments given by governments to households without conditions on how the money can be used) programmes is estimated at ₹1.7 lakh crore in FY26. And the number of states running these schemes has grown more than five-fold between FY23 and FY26. The worrying bit? Nearly half of these states are already in revenue deficit. Which means if they want to spend on development, they’ll have to borrow more. And that’s exactly the kind of debt-led spending India is trying to move away from.

This is also where global investors start getting uneasy. Now that Indian bonds are part of global bond indices, investors don’t just look at the centre’s finances. They look at the “general government” — the centre plus the states. You can see this in how markets price India’s debt versus Indonesia’s. India’s 10-year bond yield sits at around 6.7%, while Indonesia’s is lower at about 6.3%, even though both countries have the same credit rating. In other words, investors demand a higher return to lend to India.

Because they’re probably thinking “Hey, India’s central government finances look good, but states look messy. So maybe India’s overall risk is higher than the rating suggests.”

Of course, the centre will try its best to keep things under control. And one way it’s already doing that is by using its own balance sheet to influence how states spend.

Remember SASCI, which we mentioned earlier in the story?

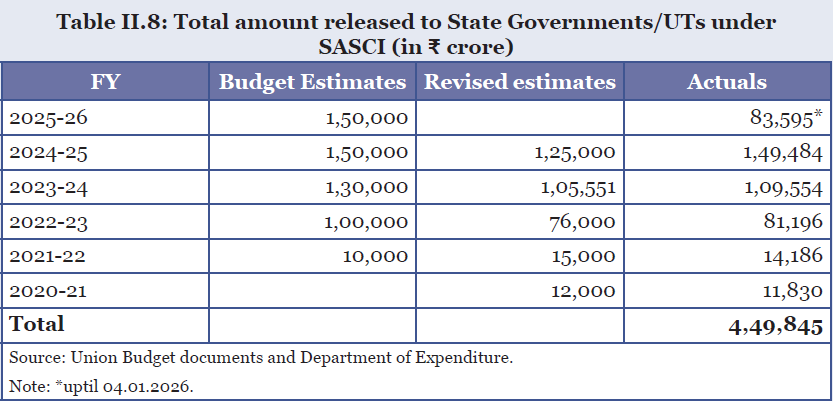

Launched in 2020, SASCI offers states 50-year, interest-free loans, but only for capital projects. And the scale of this programme has exploded. To put it in perspective, the amount released to states and Union Territories under SASCI has jumped from ₹12,000 crore in FY21 to ₹1.5 lakh crore in FY25. Taken together, the centre has already lent about ₹4.5 lakh crore since the scheme began.

Now, SASCI isn’t the villain here. In fact, it acts as a stabiliser. Without it, states’ capital outlay would have slipped from 2.11% to 1.92% of GDP between FY22 and FY25. But with SASCI in the picture, overall state capex has stayed broadly stable at around 2.3–2.4% of GDP, with poorer states relying on it more heavily.

That’s where the problem creeps in. States may be increasingly shifting their own resources towards avoidable revenue spending, while depending on the centre’s 50-year, interest-free money to fund infrastructure and other essential capital projects — the very spending that actually drives long-term growth.

And that’s the paradox we were talking about. India’s macro story still looks strong. Inflation has cooled to 1.7% as of December 2025. Core inflation excluding food, fuel, and precious metals, is hovering around 2.9%. And potential growth has been revised up from 6.5% to 7%. By most measures, India appears to be growing steadily, even as global uncertainty lingers.

But beneath all that optimism sits a tougher question: how long can a fiscally disciplined centre keep supporting states that are spending more than they earn?

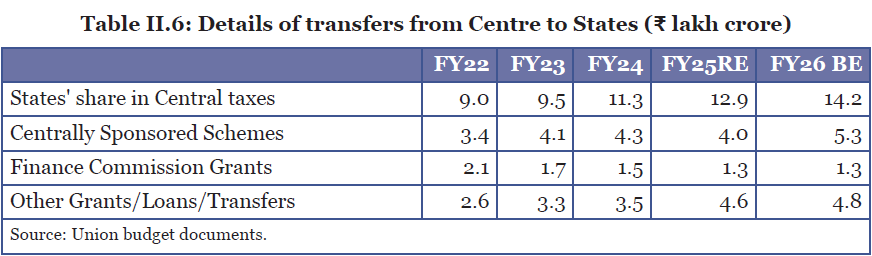

Because the Economic Survey makes it clear that transfers from the centre to the states have more than doubled from ₹11.5 lakh crore in FY20 to a budgeted ₹25.6 lakh crore in FY26. In GDP terms, that’s a jump from 5.7% to 6.9%. On top of that, money recommended by the Finance Commission meant to help states cover revenue gaps and fund local bodies, adds another ₹1.47 lakh crore in FY26, with nearly half of it already disbursed by December end. And then there’s SASCI, which now props up a meaningful chunk of state capital expenditure.

So yeah, for now, this arrangement works. The centre’s fiscal discipline and borrowing strength are keeping things stable. But if states keep spending more on giveaways without growing their revenues, the centre–state fiscal balance itself could start holding back India’s growth.

What do you think?

Until then…

Note: An earlier version of this story carried an incorrect expansion of SASCI due to oversight. We apologise for the error and have now corrected it.

Liked this story? Why not share it with a friend, family member or even a curious stranger on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X?

How Strong Is Your Financial Plan?

You’ve likely ticked off mutual funds, savings, and maybe even a side hustle. But if Life Insurance isn’t a part of it, your financial pyramid isn’t as secure as you think.

Life insurance is the crucial base that holds all your wealth together. It ensures that your family stays financially protected when something unpredictable happens.

If you’re unsure where to begin, Ditto’s IRDAI-Certified insurance advisors can help. Book a FREE 30-minute consultation and get honest, unbiased advice. No spam, no pressure.