The gold rush begins at home

In today’s Finshots, we talk about how private gold mining might be the first step to reducing India’s reliance on imported gold.

But here’s a quick sidenote before we begin: 18% GST on Insurance Is Gone. What Now?

Since 22nd September, the 18% GST on insurance premiums has been removed. Policies are now cheaper, but the real question is: which one should you get and how much cover do you actually need?

That’s where our 2-day masterclass comes in. We’ll break down health and life insurance in simple, jargon free steps so you can make the most of this change and avoid costly mistakes.

👉🏽Click here to reserve your spot today!

Now, onto today’s story.

The Story

Indians and gold. It’s a love story that never ends. Whether it’s for weddings, savings, or just as an investment hedge, we can’t get enough of it. And to satisfy this appetite, India imports a thousand tonnes of this yellow metal. Yep, 1000 tonnes of gold every year! But when it comes to producing our own, the number is laughably small at just 1.5 tonnes.

Which begs the question - When there’s such a steep demand, why haven’t we mined for gold at home?

Well, we have mined in the past. And that’s also part of the reason why we haven’t anymore. Let us explain.

The Kolar Gold Field (KGF), once the pride of Indian mining, churned out around 800 tonnes in the 120 years it was active before shutting down in 2001. The reason India stopped mining at KGF was because of a list of concerns. It was active for a long time, and that meant with more gold mined, the next extraction would be deeper. At one point, it was the 2nd deepest gold mine at 3,200 meters depth. And when you have to dig deeper, it costs more to extract gold. Think power costs, ventilation systems, water pumping all adding to the cost of getting the shiny metal out from underneath. And then there’s the environmental hazards that mining caused, especially contaminated water, land and infrastructure. So sure, it was the biggest gold mine of the country at the time, but after a point it was no longer viable.

The closest we came to KGF was Hutti Gold Mine which gave us around 84 tonnes of gold between 1947 to 2020. So even if you put both these mines together, they didn’t move the needle. And even with the current active mines, we barely make enough to meet demand. That’s why we’ve been a net importer of gold, buying from around 48 countries.

Now you might be wondering, sure, the existing mines have run out of gold or they don’t make enough. So… why not look for more gold reserves?

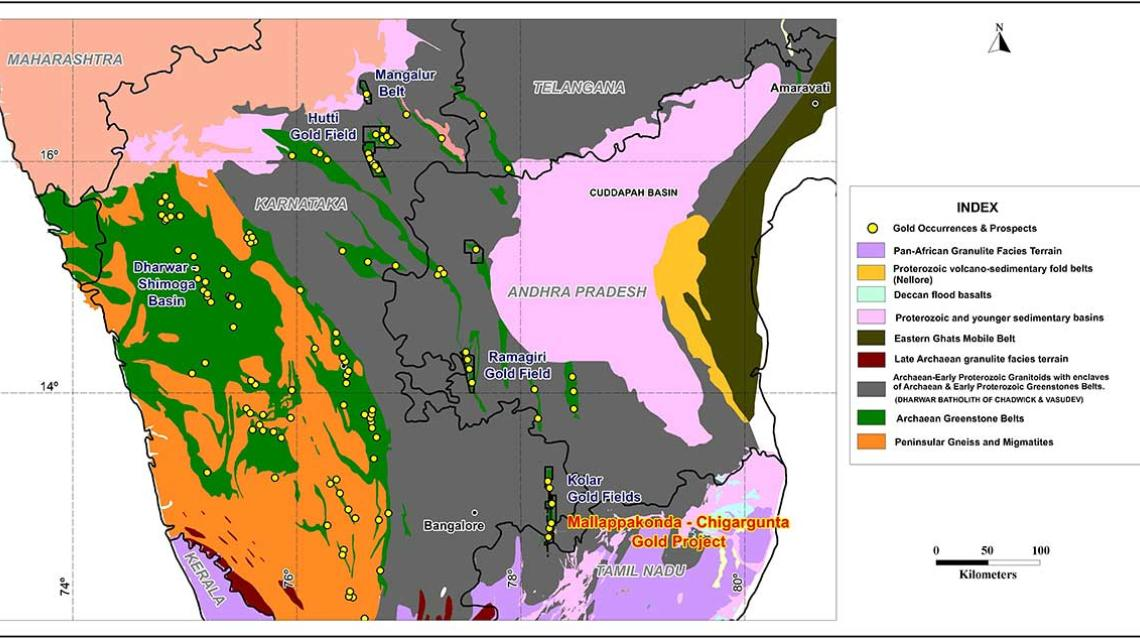

Well, we have looked for them, and even know where they are. Most of the reserves sit in the southern belt of India, and Karnataka alone holds 88% of them. The remaining 12% sit in Andhra Pradesh. But for the longest time, the issue wasn’t where the gold reserves were, it’s how to get to them with the policies behind gold mining.

You see, until recently, there hadn’t been any true push for domestic gold mining. Most of the control here is with the government and companies never found it feasible to even bid for mining leases.

Why’s that, you ask?

Because for decades, mining these reserves was tied up in policy knots. All gold mining operations needed approval from the central government. But the actual licenses were handed out by the state government. There was no transparency nor was it based on competitive bidding. And even if a miner did manage to win the auction, there’s all the approvals that a private company needs: environmental clearances, wildlife approvals, forest clearances and land acquisitions. In short, starting a mine seemed like a paperwork nightmare before a single ounce of gold could be dug up.

But all of this changed with the new 2023 Mines and Minerals (Development and Amendment) Bill. It introduced exploration licences (ELs) for private players, letting them scout for critical minerals — gold included — something the 1957 Act never allowed.

Auctions were revamped too. Under a new reverse bidding system, exploration companies bid by quoting the smallest share they want from any future mining lease premium. So say if an exploration company discovers a viable gold deposit and the subsequent mining lease auction generates ₹100 crores in premium, the exploration company receives their quoted percentage share. In other words, exploration finally comes with a direct financial incentive.

And we’re already seeing the first proof of concept: The Jonnagiri gold project.

Located in the same belt as Karnataka’s gold mines, Jonnagiri is part of the East Dharwar craton in the Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh. And it’s run by the Deccan Gold Mines Ltd (DGML), India’s only listed gold exploration/mining company. It’s also the first private gold mine, the first new discovery since Independence, and the first to be developed entirely under the 2023 exploration-license regime. That’s a lot of firsts from one project.

And DGML followed through with environmental and land approvals that once kept private players out.

In other words, it’s telling that the new policy can actually work. Once it’s fully operational, it could produce 750 kilograms of gold in its first year. Sure, it’s not as large as a thousand tonnes coming in from abroad. But it’s a statement that, this time, the gold rush isn’t at Kolar or Hutti, it’s in the hands of private miners. And when we’ve been producing just 1.5 tonnes, that extra production can boost outputs by 60%!

Fun fact:This isn't the first time gold mining came to Jonnagiri. Old debris and pounding marks indicate that the area has been worked by the ancients for recovering gold. These ancient workings led the Geological Survey of India to carry out a detailed investigation in 1991.

But here’s the million-dollar question: Will all of this really reduce our dependence on imported gold?

Not immediately. Against annual demand of 800–1,000 tonnes, a few hundred kilos won’t change much.

But it’s an important precedent. Because the same policy framework could unlock other critical minerals too. Apart from gold, a total of 107 blocks of minerals were given to state governments for auction, but only 19 were actually auctioned. So the central government took over the mining lease auctions for rhenium, tungsten, cobalt and many other minerals. Faster auctions mean production can start sooner and we can finally see real use of our minerals. And as more private explorers enter the field, new deposits could be discovered and India’s dependence on costly imports could gradually reduce.

Until then…

Sharing is caring. If you found this story useful, please do consider telling your friends about it. All you have to do is send it on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, or X and ask them to subscribe! :)