The economics behind a common language

In today’s Finshots, we look at the pros and cons of having one common language spoken across different regions in a country as diverse as India.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

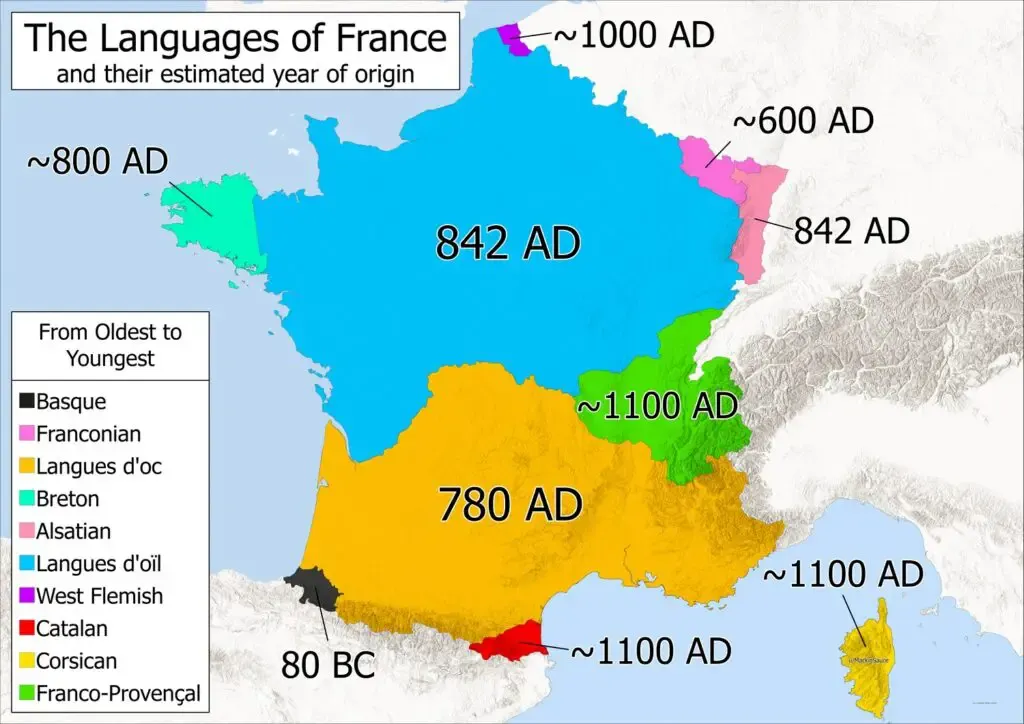

Before the 18th century, the region we now call France didn’t speak modern French. It was a mosaic of languages and dialects that had evolved from Latin over centuries. There were French dialects like Picard, Norman, and Occitan. And then there were entirely different regional languages such as Breton, Basque, and Alsatian. Each came with its own sense of identity. France, linguistically speaking, was anything but unified.

However, in 1539, François I, the then King of France, signed the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts into law, mandating the use of French on all public documents.

And in 1882, the Jules Ferry laws prohibited the use of regional languages in schools, while providing free, secular education in France. This is widely considered to be the beginning of the decline of French regional languages.

Because, you see, post the French Revolution, a standard French language was mandated not just to build political unity, but to remake the economy itself. The revolutionaries argued that linguistic standardisation could lower barriers, align markets, and pull a fragmented country into a single unified nation.

Language is usually discussed as culture, identity, or emotion. But one can also look at it through an economic lens, as language behaves more like infrastructure. Much like roads, power grids, or payment systems, it determines who can interact with whom, how easily labour can move, how quickly skills transfer across regions, and how firms scale. In that sense, language really shapes access to markets and opportunities long before politics or governments enter the conversation.

A shared language reduces transaction costs across an economy, and communication becomes easier. Workers will find it easier to move across regions, firms spend less resources on training and translation, and ideas will spread faster between markets.

Over time, this improves productivity and allows capital to flow more freely, because information asymmetries are lower and integration costs fall. This is why large economies and even corporations tend to converge on a common working language, even when cultural diversity remains.

While all this is true, linguistic fragmentation performs a different economic function. It preserves local identity, social trust, and participation within communities. But it also raises coordination costs. Workers are more tightly bound to local labour markets, and productivity gains diffuse unevenly across regions. Growth still happens, but it happens in pockets rather than at scale.

Every large economy, therefore, faces an unavoidable trade-off between efficiency and inclusion. What makes language policy particularly sensitive is that this trade-off is rarely acknowledged in economic terms.

Instead, debates are framed almost entirely around politics, while the underlying costs remain implicit. Over time, those costs compound through wages, mobility, and economics.

Let’s understand this with an example.

India illustrates this tension with unusual clarity because of our diversity. In a multilingual setting, the concept of linguistic distance becomes economically important. Linguistic distance refers to how easily speakers of one language can learn or understand another. Languages such as Bhojpuri or Haryanvi are structurally closer to Hindi, whereas languages like Kannada or Tamil are much farther away. This difference translates directly into learning costs.

When the official language imposed by the state does not match the local language, learning outcomes suffer. In fact, a study tracking Indian districts formed during colonial reorganisation showed lower literacy and graduation rates in linguistically mismatched regions. The same pattern appears globally. Immigrants exposed early to the dominant language perform better than those who are not. A common language can improve coordination and efficiency, but when it is enforced rather than chosen, behavioural responses like resistance and disengagement often undo those gains.

As a result, the economic burden of adopting a common language is not evenly distributed. Some groups face relatively low adjustment costs and gain quicker access to national labour markets and institutions. Others face higher costs in terms of time, effort, and foregone opportunities. These asymmetries shape this behaviour.

Groups that bear higher learning costs are understandably less willing to accept linguistic standardisation, not merely for cultural reasons, but because the economic burden falls disproportionately on them.

In this context, what often appears as resistance to a language is more accurately a resistance to unequal cost-sharing. The disagreement is not about communication itself, but about who pays for coordination and who benefits from it.

In France, for instance, there was a minor backlash from the priests for alienating Latin. This was because Latin was the official language of the Church and courts back then, and promoting French did not feel right to them. However, the masses did not mind because primary education in the standard French language was made free. In a country that was primarily engaged in farming back then, this was a significant economic incentive to formally educate their children.

In India, though, there is no such incentive to promote a single language across the entire country.

So, when such an incentive does not exist, and the linguistic gap is greater in certain states, language debates become emotionally charged because they map directly onto economic outcomes such as mobility, earnings, and access to capital.

At the same time, preserving local languages has its own economic value. Trust, participation, and social cohesion influence how local economies function. People are more willing to engage in economic systems they feel represented in, and exclusion can generate long-term inefficiencies through disengagement and political friction. Ignoring these effects can undermine growth even if short-term coordination improves.

The mistake lies in treating language as either a cultural issue or a growth issue. In reality, language choices involve a trade-off between near-term efficiency and long-term inclusion. Economies that prioritise coordination alone may unlock faster integration in the long term, but they accumulate exclusion risks that surface later. Economies that prioritise identity without coordination protect participation but limit their ability to scale.

While it worked for the French, the mistake is framing language as culture vs growth. Because in India, we are too big and diverse to just have one language. Our tradition, culture, and even food are linked to our mother tongue, which may differ significantly from one region to another.

However, in France, most languages came from just Latin. Add to this that France is a physically smaller country than India. So, their culture is not entirely different from region to region. At least, not as much as India.

Language, therefore, does more than shape communication. It influences how opportunity is distributed across an economy, affecting wages, mobility, growth, and access to markets. Treating language as purely cultural obscures these economic mechanisms, and that itself carries a cost. But that cost is worth it when the latter choice is preserving local languages and sustaining identity.

Until then…

Don’t forget to share this story with a friend, family member or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

🚨Term Life Insurance Prices are About to INCREASE!

A prominent insurer is set to raise their term insurance rates in the next few days. This means if you don’t secure a term plan now, your premiums could significantly go up!

Here’s why this matters: When you purchase a term life insurance policy, you pay a premium or a small fee each year to protect against financial risks. In the unfortunate event of your passing, the insurance company pays out a substantial sum to your family or loved ones.

The best part? By buying early, you can lock in your premiums, ensuring they're not affected by any future rate hikes.

If you've been considering a term plan, now is the perfect time to act. To assist you in the process, our advisory team at Ditto is here to help. Click on the link here to book a FREE call with our IRDAI-certified advisors.