The Budget 2026 explained

In today’s Finshots, we break down the most important highlights from the latest Budget.

But just a heads up before we dive in. This is one of those stories that’s a bit longer than usual, so we’ve divided it into sections that you can pick and read at your own pace.

The Story

For a country to truly grow, manufacturing can’t be an afterthought. Every major economic powerhouse figured this out early. The US built its dominance by building more factories during the Second World War, which provided employment. China followed a similar playbook, using manufacturing to absorb labour, boost exports, and climb up the value chain.

Sure, services such as banking or consulting helped. But it was manufacturing that stitched everything together.

That’s the context in which this year’s Budget needs to be read. It doesn’t bet on a single headline-grabbing scheme. Instead, it tweaks incentives across sectors to make producing in India cheaper, easier, and exporting finished goods a little more attractive. And when you add it all up, a clear manufacturing story begins to emerge.

And once you start looking at the 2026 Budget through this manufacturing lens, the intent becomes very clear.

The clearest signal comes early in the speech. Under the first kartavya of accelerating growth, the Finance Minister commits to scaling up manufacturing in seven sectors.

Let’s start with biopharma. India’s disease burden is shifting rapidly toward non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and autoimmune disorders. To address this and reduce dependence on imported drugs, the Budget launches Biopharma SHAKTI, a strategy to build India into a global biopharma manufacturing hub.

This programme carries an outlay of ₹10,000 crore over five years and aims to create domestic capacity for biologics and biosimilars, establish over 1,000 accredited clinical trial sites, and strengthen the CDSCO (Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation) with a dedicated scientific review cadre to meet global approval timelines.

Next comes semiconductors and electronics. In December 2021, the India Semiconductor Mission or ISM 1.0 was launched. ISM 1.0 was focused on the fabrication and design of semiconductors. Now, with the launch of ISM 2.0, the government wants to expand the scope to producing semiconductor equipment and materials, building Indian IP in the industry, and creating an industry-led research and training ecosystem for skilled manpower.

Alongside this, the government proposes to sharply scale up electronics manufacturing incentives. In fact, the Electronics Components Manufacturing Scheme, launched in April 2025, which has an outlay of ₹22,919 crore, has already attracted investment commitments at double the target. To capitalise on this momentum, the Budget raises the outlay to ₹40,000 crore. This is the most explicit capital-backed push for electronics and semiconductor-linked manufacturing in the speech.

However, to manufacture semiconductors, we need rare-earth materials. And this is where the manufacturing conversation takes a geopolitical turn. A Scheme for Rare Earth Permanent Magnets, launched in November 2025, is now being operationalised on the ground.

The Budget also proposes to support mineral-rich states, like Odisha, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, to establish dedicated Rare Earth Corridors. These corridors will span mining, processing, research, and downstream manufacturing. The hope is that this will eventually secure access to critical materials that underpin electronics, clean energy, and advanced manufacturing.

Another related sector is chemical manufacturing. To reduce import dependence, the government proposes a new scheme to support states in setting up three dedicated Chemical Parks, aimed at lowering entry barriers for manufacturers and strengthening the domestic chemical supply chains that feed into pharma, electronics, energy, and infrastructure.

Finally, to tie all this together, the Finance Minister proposes a ₹10,000 crore SME Growth Fund to provide equity support to high-potential MSMEs. It also tops up the Self-Reliant India Fund by ₹2,000 crore to ensure continued access to capital for such micro enterprises.

And while manufacturing has been front and centre in the Economic Survey and the Budget, there’s another fresh term that sort of made its debut this year. It’s called the orange economy.

You caught a glimpse of it in the Budget speech. The Finance Minister proposed backing the Indian Institute of Creative Technologies (IICT), Mumbai, to help set up AVGC Content Creator Labs in 15,000 secondary schools and 500 colleges. These labs would give students early, hands-on exposure to animation, VFX, and gaming before they enter the job market.

Now, you may have been curious about the term “orange economy” and then brushed it off while listening to the proposal. But there’s something about this idea that isn’t worth brushing off.

See, the orange economy is everything that makes money from things like music, films, art, design, and performances. And concerts sit right at the heart of it.

Now, you might think of concerts as just buying a ticket and getting entertained. But look a little closer and you’ll see something else happening. A big live show sets off a chain reaction across the economy. People travel to the city, book hotels, eat out, use local transport, rent equipment, and create content around the event. In other words, one concert quietly ends up feeding many businesses at once.

And the Economic Survey has real evidence to back this up. In the UK, music-related tourism contributed about 0.3% of GDP in 2022, largely by boosting hotels, transport, and retail. And according to UNCTAD estimates, creative industries contribute anywhere between 0.5% to over 7% of GDP across countries. All of this simply shows how much economic potential live entertainment really holds.

Okay, but Finshots, how does setting up content creator labs related to all this, you ask?

Well, it is because concerts today aren’t just about people standing on a stage and singing. They can be virtual. They can have virtual stages layered into live shows. Or they can offer fully immersive experiences.

And all of that needs skills like visual design and graphics, AR (augmented reality) and VR (virtual reality) effects, and digital content for promotion, streaming, and fan engagement. These skills are no longer niche and are becoming serious job creators. In fact, by 2030, the industry is expected to need around 2 million artists, animators, designers, editors, storytellers, and tech talent.

But since India’s orange economy is still nascent, we’ll need to train people early so that we can meet future demand and turn creativity into a real engine of growth.

So yeah, that’s what this proposal is really about.

That brings us to the bit about agriculture and increasing farmer incomes.

Now, it’s true that agriculture’s share in India’s GDP has been shrinking. For context, in 1991 it contributed about 35% of GDP, but today that number has fallen to around 18%. But what hasn’t changed is its importance. Agriculture still employs nearly half of India’s population.

And that’s where the challenge lies. The government has to find ways to raise farmer incomes without endlessly increasing MSPs or subsidies because that would eventually put pressure on public finances.

So the easiest route?

High-value crops.

These crops generate more value per hectare and per worker than staples like rice and wheat. That’s exactly why, alongside measures to improve animal husbandry and fisheries, the Budget places a clear emphasis on high-value agriculture.

Coconut gets special attention for a reason. India is already the world’s largest producer, and nearly 30 million people depend on it for their livelihood. The problem, though, is productivity. Many coconut trees are old and yield less. That’s why the Finance Minister proposed a Coconut Promotion Scheme to replace ageing trees with newer, higher-yielding varieties, helping boost output and incomes without expanding farmland.

Although the Budget doesn’t explain what this scheme involves, it will likely include some form of temporary income support for coconut farmers while old trees are replaced. That’s because farmers are unlikely to replace ageing trees on their own without policy backing, as coconut trees take 5 to 7 years to flower and bear fruit. So, even phased replacement would mean a temporary hit to incomes while the new trees mature, ultimately keeping productivity low.

There’s also a push to support crops that make sense for each region such as reviving sandalwood and cashew in coastal areas, promoting agar trees in the North East, and making India self-reliant in cocoa production as domestic demand for chocolates and confectionery keeps rising.

Plus how can we forget Bharat-VISTAAR, a multilingual AI tool for agriculture? It will integrate AgriStack data (a digital database that focuses on farmers and agriculture) and ICAR’s knowledge on farming practices into AI systems. This will help farmers get customised, local advice in their own language so that they can improve crop productivity, support better decisions, and reduce risks in farming.

And then finally, comes everyone’s most favourite part — capital markets, personal finance and taxes.

Because we all know that secretly, we were all waiting for this part even though there would likely be very little benefit, since this had already been addressed in the last Budget and through the recent GST rate rationalisation.

The most obvious being any changes in personal taxes. And depending on which side of the tax slab you’re sitting on, this could be either good or bad news because there was no change in income-tax slabs this year.

But that said, some things did change in terms of personal finance.

For starters, TDS on the sale of immovable property by a non-resident will now be deducted and deposited using the resident buyer’s PAN (Permanent Account Number) instead of a TAN (Tax Deduction and Collection number). In simple terms, if you’re buying property from an NRI, you no longer need to apply for a separate TAN just to deposit TDS — your PAN will do the job. It doesn’t reduce the tax, but it does remove a lot of unnecessary paperwork for one-time buyers.

But one thing stood out more than the rest, and it affects anyone with a demat account in India.

STT (Securities Transaction Tax, the tax paid every time you buy or sell securities) saw a sharp hike. STT on option premium was raised to 0.15% from 0.10%, a 50% increase, while futures saw the biggest jump — from 0.02% to 0.05%. All of this kicks in from April 1, 2026.

This isn’t the first time STT has been raised. And historically, every time the government hikes it, collections tend to fall. Until January 11, STT collections stood at around ₹44,500 crore, well below the government’s projection of ₹78,000 crore — a reminder that higher transaction taxes don’t always mean higher revenues, especially in markets driven by volumes. But with the higher STT, maybe speculation will fall and so will losses of retail traders.

Then the Budget has quietly closed a long-standing loophole around share buybacks by changing how they are taxed. Earlier, when shareholders tendered shares in a buyback, the payout was treated as a deemed dividend. This meant that tax was charged on the entire amount at slab rates, without allowing any deduction for the original cost of buying the shares. That cost had to be adjusted separately against other capital gains or carried forward. Dividends were taxed the same way — on the full amount, at slab rates.

But this system created an imbalance. Large promoters often preferred buybacks over dividends because buybacks allowed them to use capital losses elsewhere and sharply reduce their true tax rate. Small public shareholders, meanwhile, simply paid slab-rate tax on the deemed dividend.

The Budget fixes that as buybacks will now be treated purely as capital gains for everyone. On top of that, promoters will have to pay an additional buyback tax bringing the effective rate to 22% for corporate promoters and 30% for non-corporate promoters.

In short, the tax arbitrage is gone, and buybacks and dividends are now taxed more evenly. So no more kicking the can down the road 😉

On the compliance side, the government offered some relief. Investors now have more flexibility to revise and update income-tax returns, making it easier to fix errors in capital-gains reporting, dividends, or foreign income. At the same time, disclosure rules for foreign assets and overseas investments have been tightened, signalling that transparency — not leniency — is the long-term direction of travel.

Some other changes also caught our attention. For example, any interest awarded by the motor accident claim tribunal is completely exempt from income tax plus there’s no TDS on the award as well. And also sovereign gold bonds (SGBs) will be exempt from capital gains tax only when the investor who bought them on Day 1 holds onto them until they mature.

Put together: shortcuts, speculation, and opacity are getting costlier, while long-term investing itself remains largely untouched.

With that, it’s a wrap on the key highlights of this Budget.

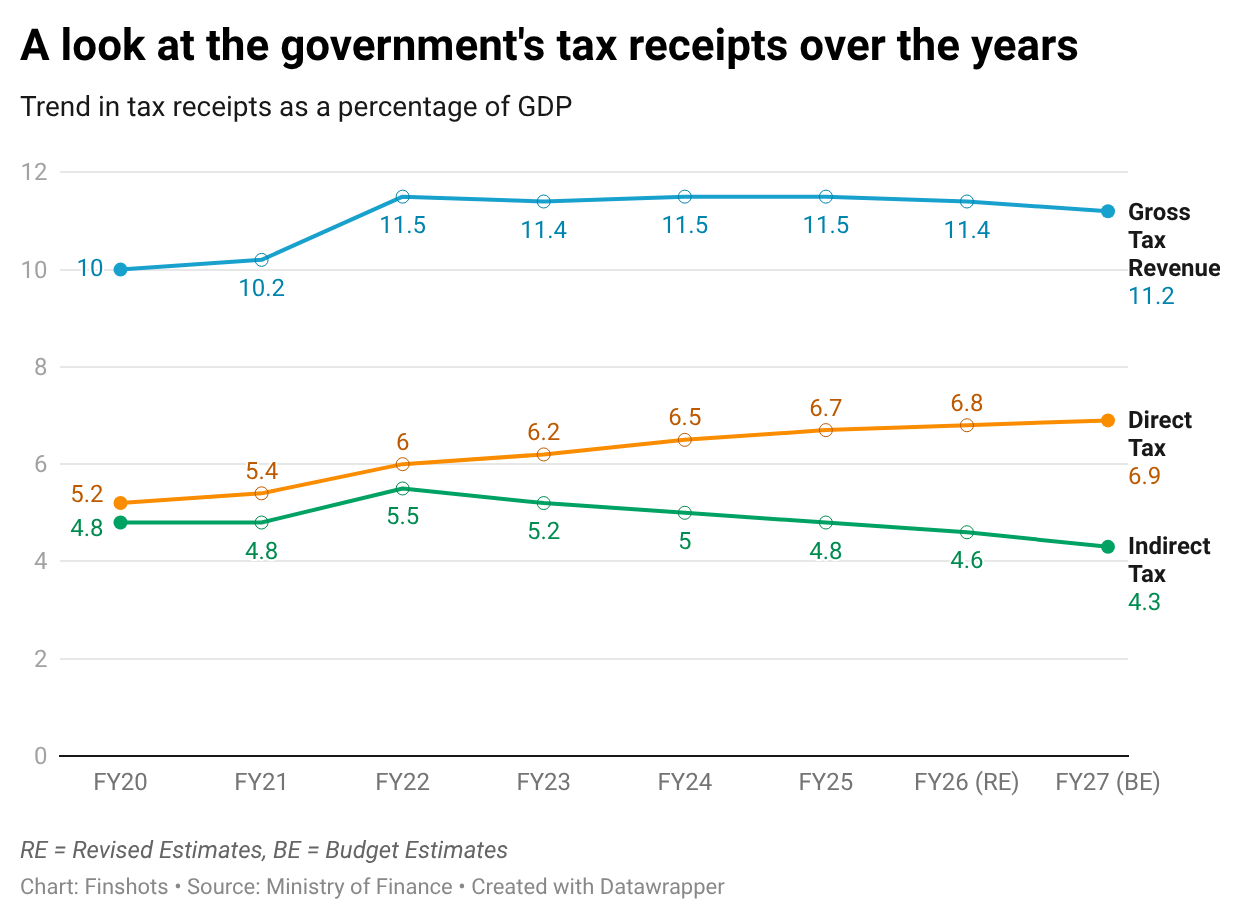

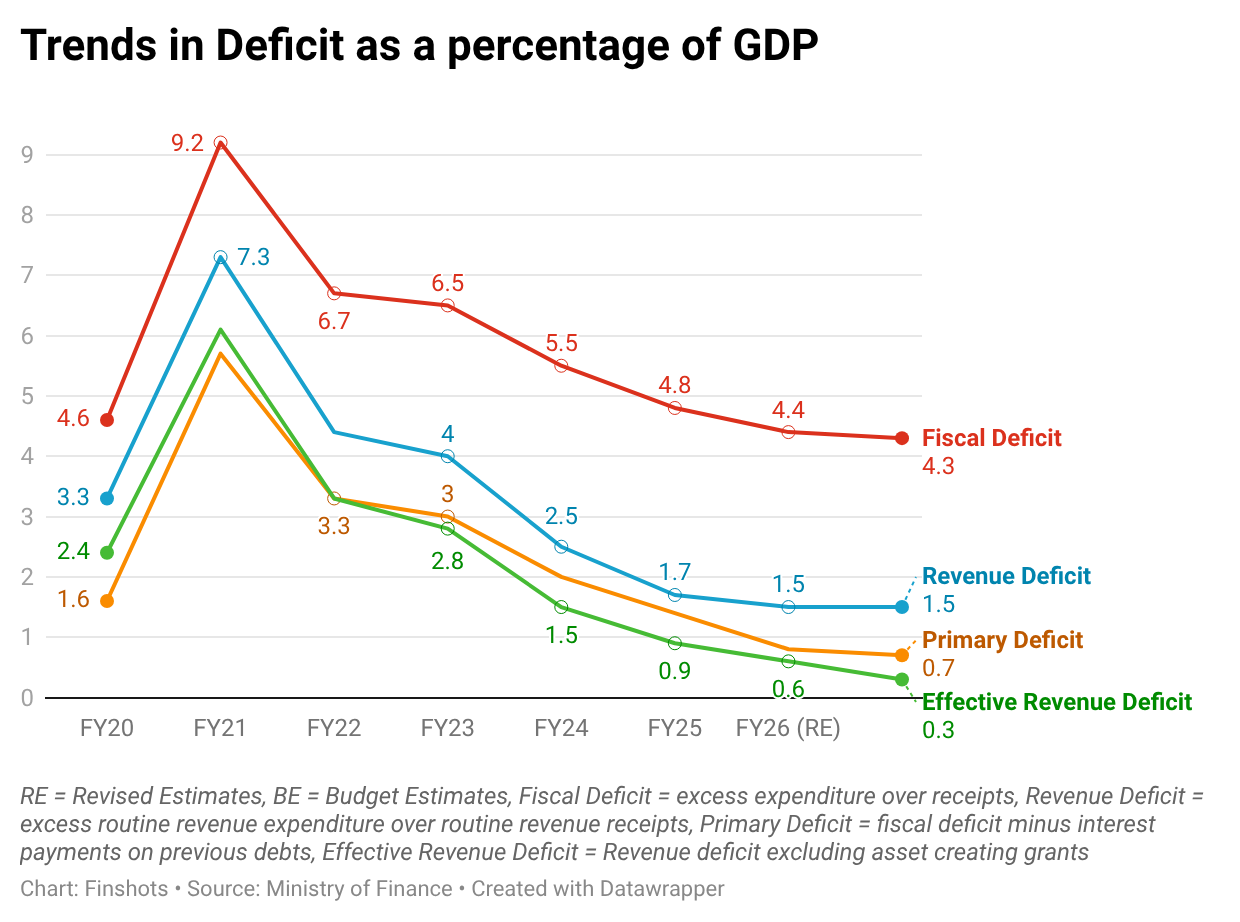

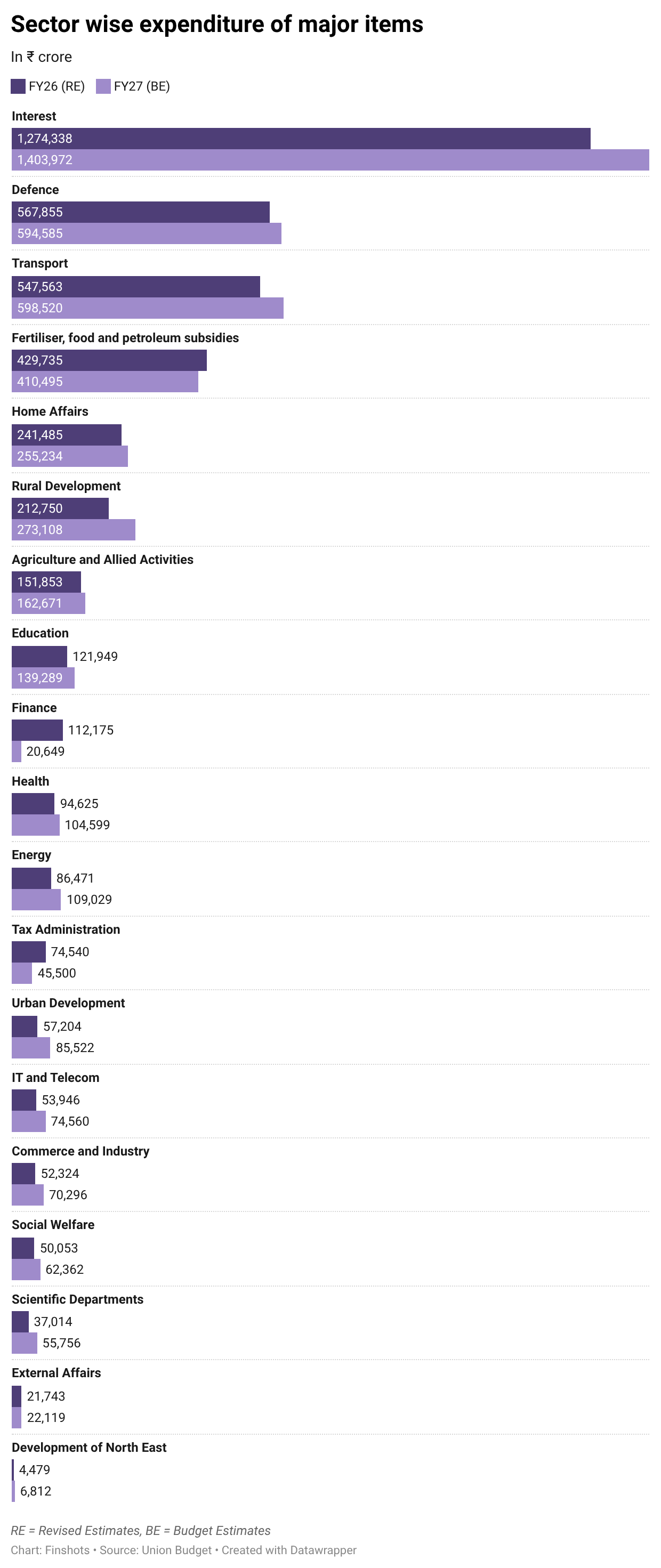

And to give you a clearer picture of the state of India’s finances and how much we’re spending on what, we’ve also put together a few charts and graphs below:

Until next time...

If this story helped you make sense of this year’s Budget, share it with your friends, family, or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and X.

Message to All the Breadwinners

You work hard, you provide, and make sacrifices so your family can live comfortably. But imagine when you’re not around. Would your family be okay financially? That’s the peace of mind term insurance brings. If you want to learn more, book a FREE consultation with a Ditto advisor today.