The $1.5 trillion SpaceX IPO Explained

In today’s Finshots, we look at why people are whispering about a $1.5 trillion SpaceX IPO, and why that number both excites and unsettles markets.

But here’s a quick sidenote before we begin. This week, we’re hosting a free 2-day Insurance Masterclass where we’ll walk you through simple rules to pick the right insurance plan and the common mistakes you should avoid.

📅 Tuesday, 16th Dec ⏰at 6.30 PM: Term Insurance

How to protect your family, choose the right cover amount, and understand what truly matters during a term claim.

📅 Wednesday, 17th Dec ⏰at 6.30 PM: Health Insurance

How hospitals process claims, common deductions, the mistakes buyers usually make, and how to choose a policy that won’t disappoint you when you need it most.

👉🏽 Click here to register while seats last.

Now, on to today’s story.

The Story

For as long as humans have looked up, space has represented both possibility and insignificance. Ancient sailors used the stars to navigate oceans they barely understood. Astronomers mapped distant galaxies, knowing they would never reach them. And governments spent billions during the last century not just to plant flags on the Moon, but to prove technological supremacy back on Earth.

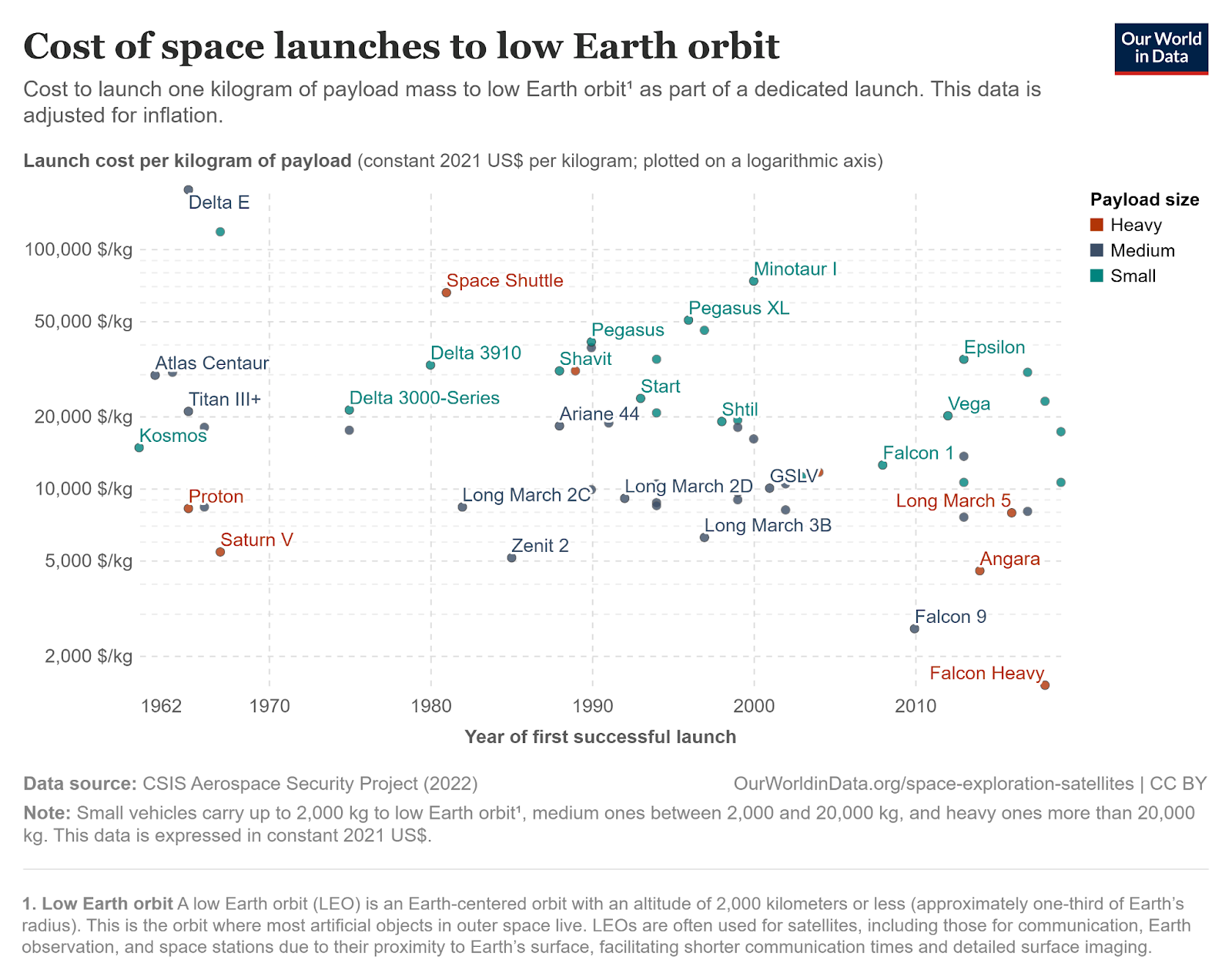

However, for decades, the one brutal reality that has always constrained space exploration was cost. It was astronomically expensive, politically motivated, and rarely profitable. Rockets were built to be used once. Failures were accepted as the cost of ambition. And the idea that space could be a commercial industry rather than a government programme felt almost absurd.

Because for decades, launching a single kilogram into orbit could cost tens of thousands of dollars. This was because rockets were discarded after a single use, and innovation moved at the pace of government procurement cycles.

So even if the technology existed, the economics simply did not. As a result, space remained the domain of superpowers. NASA, ISRO, Roscosmos, and a handful of state-backed agencies dictated who could go up, when, and why.

But that assumption quietly collapsed over the past two decades. Space is no longer just about national pride or scientific curiosity. It is becoming infrastructure. And at the centre of that shift sits a private company that now wants public investors to join their journey into the stars.

You see, a few days ago, an eye-popping number started doing the rounds on Wall Street: $1.5 trillion. That’s what some bankers and private-market analysts believe SpaceX could be worth if and when it goes public. To put that in perspective, that would make SpaceX more valuable than Apple and Meta on listing day, and roughly a third of all the listed companies in India.

It sounds absurd. And yet, the chatter refuses to die down. SpaceX’s latest private-market valuation (around $800 billion) already makes it the most valuable private company on the planet. Add to that that SpaceX now launches more rockets than every other country combined and controls over 60% of global orbital lift capacity (basically how much mass a company can send into space over a period of time).

And Starlink, its satellite-internet arm, has millions of paying subscribers and thousands of satellites in orbit, forming the largest constellation we have ever built (we, as in humans).

This got the ball rolling: if Starlink were spun off and listed separately, it could itself be worth hundreds of billions. Stitch that together with SpaceX’s launch business and future projects like Starship, and the $1.5 trillion number doesn’t look completely deranged.

Because SpaceX isn’t a normal company. And Elon Musk isn’t a normal founder either.

For most of his career, Musk has actively resisted public markets. He has repeatedly said that taking Tesla public was painful because they were forced to make short-term decisions and engineers were distracted from actually building.

So SpaceX was deliberately kept private. It was Musk’s sandbox for high-risk engineering, where rockets could explode, timelines could slip, and millions could be burned in pursuit of goals that might take decades to materialise.

Which is why it was surprising when Elon himself called the rumours accurate.

So if Musk, of all people, is now open to listing SpaceX, the obvious question is why.

Well, the most straightforward answer is scale. SpaceX is entering a phase where private capital may no longer be enough. Starship development, Starlink satellite replacements, lunar contracts, defence launches, and deep-space ambitions all require capital on a scale that private markets simply struggle to sustain indefinitely.

There’s also a quieter, more speculative reason. Interest in space-based data centres is picking up, especially as companies prepare for a world shaped by AI, and eventually, AGI. Training and running these frontier models demands enormous computing power, energy, and cooling capacity. Putting parts of that infrastructure in orbit or near space could, in theory, solve constraints around land, power availability, and latency for global data transmission. SpaceX is unusually well-positioned here.

An IPO dramatically widens the funding pool and gives SpaceX liquidity to fund such projects whose timelines may not be defined as such.

However, the public markets don’t fund visions. They fund outcomes. Shareholders will care deeply about Starlink’s margins, satellite replacement costs, regulatory risks, and free cash flow. They may be far less enthusiastic about rockets exploding during test flights or billions being poured into Mars missions with no clear commercial return. And all of that could create a fundamental tension.

On the upside, SpaceX has done something few incumbents ever manage: it collapsed the cost curve of an entire industry. That alone reshaped space economics.

But Starlink went a step further and changed the business model entirely. Instead of relying on lumpy launch contracts and government payments, SpaceX now earns recurring subscription revenue beamed from low-Earth orbit. They have actual customers from rural households, ships at sea, airlines, and the military.

But here’s the problem. SpaceX’s strengths are also its risks.

What happens if SpaceX’s long-term goal of making humanity a multi-planetary species doesn’t align with shareholders' interests?

Because the cost of developing the Starship, transporting cargo and humans, setting up habitats, and sustaining repeated missions could easily run north of $1 trillion. And more importantly, there is no obvious revenue model at the end of it.

From a shareholder perspective, that is a sinkhole, and history often suggests that the markets win those arguments.

That’s why the SpaceX IPO is controversial in a way few others are: whether a company can remain comfortable with failure and a long gestation period once it has millions of shareholders demanding predictability.

Then there’s the practical question of control.

Start with geopolitics. SpaceX isn’t just a commercial launcher. Its satellites shape battlefield communications. Starlink terminals have already influenced conflicts and diplomatic negotiations. A publicly listed SpaceX would sit at the intersection of markets, militaries, and foreign policy. And regulators would have to answer uncomfortable questions.

You also can’t miss the Musk factor. SpaceX thrives on high-risk engineering. Rockets explode, and prototypes can fail. And that could be alright. However, that culture only works in private markets but not so much for a public company. Imagine explaining to analysts why a Starship exploded and why that’s actually progress.

There’s also the accounting reality behind Starlink. Yes, it has subscribers. But it also has a perpetual capex requirement because satellites don’t last forever. They need constant replacement. Pricing a business that requires continuous reinvestment just to stand still isn’t easy. If Starlink is carved out, investors will have to decide whether it’s a utility company, a tech company, or something entirely new. Each comes with very different valuations.

And that’s before we even question the headline number itself.

A $1.5 trillion IPO would be unprecedented. Alibaba, Google, and Meta have not debuted anywhere close to that valuation. Even Saudi Aramco barely crossed the $1.7 trillion mark. SpaceX, by contrast, is still a capital-hungry company operating in one of the most complex industries known to mankind. The upside may be astronomical, but so is the uncertainty.

Which brings us to the real reason this conversation matters.

The SpaceX IPO is about how markets price frontier technology.

For decades, public markets rewarded predictable cash flows and penalised moonshots. SpaceX challenges that logic. It sits somewhere between an infrastructure provider, a defence contractor, a telecom provider, and, let’s face it, a sci-fi startup.

If it lists, investors will have to rethink how they value companies building things the world has never seen at scale.

And that’s why the $1.5 trillion number should be read less as a forecast and more as a signal. A signal that space is no longer a niche sector for governments, but commercial and deeply intertwined with everyday life.

Until then, the company remains private, volatile, and unapologetically ambitious.

Which, ironically, may be exactly why it works.

Note: When we say SpaceX could be “more valuable than Apple and Meta,” we’re referring to the valuations of Apple and Meta on their respective listing days, not their current market capitalisations.

Liked this story? Share it with a friends, family members or even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.