Should India rethink MRP?

In today’s Finshots, we tell you why the government is thinking about overhauling India’s MRP (Maximum Retail Price) system.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

Every morning, there’s a local rickshaw puller who sells packaged milk in my neighbourhood. It’s his side gig before he starts ferrying passengers for the day. We don’t buy from him because he charges ₹3 more than the MRP (Maximum Retail Price) printed on the packet. We stick with the local milkman instead.

Most of us are hardwired to never pay a rupee more than what’s printed on the pack. And if you ever do pay extra, it probably nags you at the back of your mind.

And that reaction makes sense. The whole point of India’s MRP system was to protect everyday buyers like you and me from retailers who once had the freedom to price products however they wanted. Before it was introduced in 1990, shopkeepers would often put a price on a product without adding local taxes. Then, when you went to the counter, they’d add extra taxes, often way more than they should. So you never really knew what you’d end up paying.

To fix this, the government made it mandatory for all packaged goods to print one final price — the MRP. That figure had to include all taxes. So when you grabbed a pack of chips, you knew exactly what it would cost.

That’s why we instinctively stick to MRP. It feels fair because it’s supposed to cover everything from raw materials and production to transport, profit margins and taxes. It’s also why shopkeepers can still give you a discount and make a profit even after shaving a few rupees off the printed price.

Besides, selling something above its MRP like that “cooling charge” local vendors add for a soft drink, is illegal except in limited cases like restaurants, where you’re not just paying for the product but also for the service. But if you’re at an airport kiosk or cinema hall buying a bottle of water or a soft drink, you can’t legally be charged more than what’s printed. Even printing different MRPs for the same product at different locations isn’t allowed.

But here’s the thing. The MRP framework hasn’t really been re-evaluated in decades. It comes under the Legal Metrology Act, 2009, which makes sure things are weighed, measured, packed and sold properly. It also says that companies must print what’s inside, the price and who made it under the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011.

But now, there’s talk that the government wants to revamp the MRP framework. Why’s that, you ask?

For starters, the problem lies in the very idea of MRP itself. Think about it. Manufacturers decide the MRP by adding up all their costs and profit margins and then print that number on the pack. But how do you, as a buyer, know if that price makes sense?

Take a packet of chips that costs ₹20. Right next to it, there might be another pack labelled “premium” that costs ₹50, even if it weighs the same and tastes almost identical. There’s no clear formula or benchmark to check whether an MRP is reasonable. That means companies can pretty much decide what they want, and that leaves a lot of room for random, unfair pricing, which is a huge problem.

Then there are the tricks some retailers play. Sometimes, they inflate the MRP so they can offer huge discounts later. Take an item with an MRP of ₹1,000. A retailer might sell it at a 50% discount. Now, it’s common sense that no retailer would sell you something at a loss. So if they’re still making money after giving it to you at half price, why was the MRP set so high in the first place? Tricks like this make you feel like you’re getting a deal when you might still be overpaying.

And finally, there’s the distribution issue. Since it’s the manufacturer who decides the MRP, it indirectly sets the profit limit for every retailer. But what if it genuinely costs more to get that product to certain places? Let’s say a new brand of oats biscuits is getting popular. Getting it to small towns with poor distribution networks might mean higher transport costs. A retailer in a remote area might not be able to cover those costs if they stick to the printed MRP. And they’re not legally allowed to charge more. So they might just refuse to stock it, which limits access. Or they might quietly sell it above MRP to make it worth their while, like that rickshaw puller selling milk for ₹3 more.

In fact, this raises a bigger question: Is capping prices still the best way to protect consumers?

Having a fixed maximum price means market forces like demand and supply can’t really influence prices. That’s not how it works in most countries. Apart from India, only a handful of places like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh still have an MRP system. In places like the US, retailers sell the same toothpaste or snack pack at different prices depending on their store, rent and other costs. If you think a store’s too expensive, you just buy it from the shop down the road. That’s competition doing its job.

Sure, you might worry retailers could form a cartel and fix prices sky high. That’s a fair concern. But countries without an MRP rely on strong competition and anti-trust laws to keep that in check, which means the market itself stops prices from getting too unreasonable.

So if the system feels outdated, does that mean the Indian government should just scrap the MRP altogether when it plans an overhaul?

Well, not really. Because you see, India is a price-sensitive market. And there’s no denying that MRP helps people know exactly how much they should pay. That’s a big deal when you think about the millions who rely on packaged goods every day.

A better approach could be to make pricing more transparent. Imagine if manufacturers had to share a simple breakdown of how they arrived at the MRP. Like a range that mentions how much goes into production, transport, taxes, margins, etc. Or maybe a QR code on the pack you can scan to see a basic cost summary. It sounds ambitious, but it’s not impossible. Some brands like FoodPharmer are already trying this by being open about how they price their products so customers know what they’re paying for.

Or if the government really wants to shake things up, they could switch from MRP to a Suggested Retail Price (SRP) or Recommended Retail Price (RRP) system like in the US and Europe. This way, retailers have some flexibility to adjust prices based on their own costs. So if a shop in a remote village has higher transport costs, they can charge a bit more and be upfront about it. Meanwhile, shoppers still know the baseline price set by the government, so they’re not in the dark. To make this work, the government could also publish average prices of common goods or add QR codes so people can compare prices instantly.

These ideas could actually give the MRP system the kind of overhaul it really needs. Something that tackles the loopholes and makes it fairer for everyone.

But for now, these are just ideas. The government hasn’t officially put anything on the table yet. From what we’ve read so far, it’s still in the early stages of figuring out how to make the MRP system better for consumers.

So we’ll just have to wait and see what happens.

Until then…

If this story helped you understand the MRP on your products better, don’t forget to share it with friends and even strangers on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

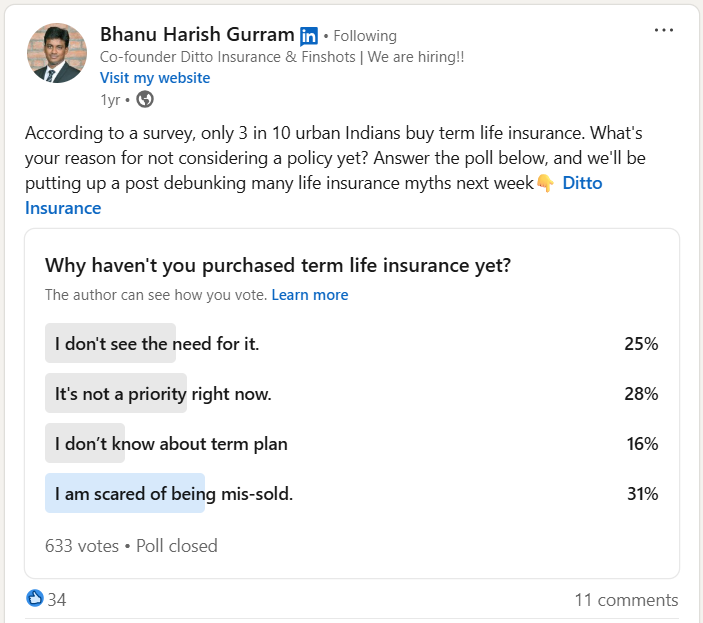

Our Co-founder Asked People Why They Avoid Term Insurance.

The Top Reason? Right Here. 👇

31% said their biggest fear is being mis-sold. Many worry that agents may push costly plans or add confusing extras without full transparency.

That's a valid concern. After all, how can you trust something you don’t completely understand?

That’s why Ditto, a product of Finshots, has pioneered India’s #1 Spam-Free insurance platform. Our IRDAI-Certified advisors offer honest advice and help you find the right plan. Book a FREE consultation today!