RBI is firefighting cash

The Reserve Bank of India conducted its monetary policy meeting last week and we haven’t talked about it yet. So let’s do that in today’s Finshots, shall we?

It’s an overly simplified version of an otherwise complex problem, so please bear that in mind.

But before we begin, if you're someone who loves to keep tabs on what's happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven't already. We strip stories off the jargon and deliver crisp financial insights straight to your inbox. Just one mail every morning. Promise!

If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

Central banks are usually worried about one big thing — liquidity. Or in simple terms, the amount of money sloshing about the system. Because if there’s too much money lying with banks, they might be tempted to lend it out too freely. Corporates could borrow and expand their business. People might take loans and spend — buy new cars, take holidays etc. Demand for everything could shoot up.

And you know what happens as a result of that right? It can push prices higher. We get the dreaded inflation.

So, how does a central bank deal with this, you ask?

Well, typically, they control inflationary worries with the biggest tool at their disposal — interest rates.

See, they have a lever called the repo rate. This is the rate at which commercial banks can borrow money from the RBI. Now if the RBI is worried about inflation, it pushes the repo higher. The premise is that if it gets more expensive for banks to borrow money when they need it, they’ll pass on the cost to people who want to borrow from them too. Basically, borrowing gets expensive and demand drops. It can quell inflation.

But that’s only half the job done.

Because liquidity could still be a problem. Banks may not necessarily pass along a higher borrowing cost initially if they’re sitting on piles of excess money. They might choose to keep lending at a low rate. And that’s where something called the reverse repo rate comes in. This is the rate at which banks can deposit money with the RBI. And in order to lure banks into depositing their excess money in its vault, the RBI can increase the reverse repo rate.

And the RBI usually deploy these levers together whenever they think inflation and liquidity could be a bit of an issue.

Sounds simple enough, right?

Okay.

Now this brings us to today. We’re actually in an environment where we have this exact problem.

Firstly, bank loan growth is booming. Some reports indicate that it’s at the highest levels in at least half a decade. Secondly, inflation’s still too high for comfort. The RBI tries to keep it as close to 4% as possible, but it’s way beyond that at the moment — it’s at a 15-month high of nearly 7.50%. We’re blaming vegetable prices.

And thirdly, banks are sitting on an excess cash pile of over ₹2.5 lakh crores. And when we say excess we mean that it’s money that banks don’t really need to meet their immediate or short-term needs. This is money above and beyond what they might need even in case of emergencies.

But how did it come to this, you ask?

Well, it is being attributed to a couple of things. Remember the withdrawal of the ₹2,000 note a few months ago? Well, it seems that nearly 90% of those notes made their way into the banking system. Sure, people might have deposited the notes and withdrawn other denominations. So if you account for that, some estimates suggest that banks were left with an additional ₹1.50 lakh crore in deposits.

Then they say that it’s because the government ramped up its spending. They’re building infrastructure and spending on things like roads and highways. And when the government spends, it eventually goes into the hands of people that do the actual work. These folks might spend some of it and they deposit some of it in the bank too. Ergo, the jump in money with banks.

Like we said, it’s the classic high liquidity plus high inflation problem.

So what do you think the conversation would’ve been at the RBI HQ when the folks met last week? Something like, “Hey, let’s increase the repo rate and make borrowing expensive. And increase the reverse repo and lure banks into depositing cash.” Right?

Well, that’s not what happened. The RBI did no such thing. The repo rate remained steady at 6.50%. And the reverse repo is still stuck at 3.35%. It was status quo.

Well, almost….

Because the RBI did decide to tweak something else — something called the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR).

See, when a bank accepts deposits, it cannot just lend it all out again to borrowers. Because depositors can ask for their money back at any time. And borrowers could renege on their payments too. So the RBI plays it safe and tells banks to keep a certain portion of these deposits in the RBI vault. It’s just for safekeeping. So the banks won’t earn any interest on this either. And at the moment, the CRR is at 4.5%. That means for every ₹100 that a bank gets as deposits, ₹4.5 goes to the RBI as liquid cash.

Now if you think about it, if the RBI wants to suck the liquidity out of the system, all it has to do is increase the CRR, no? Ask banks to part with a larger chunk of their deposits.

But the RBI didn’t want to be that cruel.

Instead, it said, “Look, the problem is that there’s been a sudden influx of money since the withdrawal of the ₹2,000 note. So let’s do this — give us the regular CRR of 4.5% and an additional 10% on all deposits you raised from the 19th of May to the 28th of July. So if you received ₹100 during this period, you park ₹14.5 with us.”

There. That should solve the liquidity problem to some extent.

But wait…why couldn’t they just raise the reverse repo instead, you ask?

Well, the only plausible explanation seems to be that even if they did, banks may not necessarily choose to park the excess under the reverse repo. They might decide to lend it out. Or invest it in other more lucrative avenues.

But the CRR isn’t voluntary. It’s a mandatory diktat and it’s a sure-shot way of getting banks to comply. That means it will have an immediate impact on the excess money in the system. If you do the math, you’ll find that with these new rules, an additional ₹1 lakh crore will be removed from the system immediately. It’ll go straight to the RBI.

Also, if the RBI thinks the liquidity problem is going to be short-lived, this is probably the easiest way to do it. They did something similar during the demonetisation experiment of 2016 too.

But wait…there’s one more thing in this picture that the RBI didn’t really talk about.

The HDFC Ltd merger with HDFC Bank.

And on Tuesday, Deepak Shenoy, an investment manager, pointed out something quite interesting here. See, HDFC Ltd was not a bank. That meant it could raise deposits, but, it wasn’t subject to the CRR rule. But after the merger, suddenly, all the deposits would be clubbed within the banking system. A CRR would be applicable on the lakhs of crores of deposits that would come flooding in.

Now the thing is that the bank also got a grace period of sorts. For one month after the merger, it didn’t have to deposit the CRR of 4.5%. This basically meant that it could invest these massive deposits elsewhere and earn a nice chunk of money. Pad up its profits.

Now that doesn’t seem fair, does it?

So maybe, by introducing this incremental CRR rule, RBI is simply trying to make up for that extra money HDFC might’ve made in that period. Maybe this has nothing to do with inflation or liquidity really. And that was just a smokescreen.

What do you think?

Until then…

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and Twitter.

PS: Some of our readers have told us that we should've mentioned how the RBI is using a tool called the Standing Deposit Facility instead of the Reverse Repo to suck liquidity out these days. While this is entirely true, the SDF has been around only for a year. And for simplicity, we focused on the 'typical' tools the RBI has used in the past many years. But in case you want to know about the SDF — current rate 6.25% — we wrote about it last year and you can read it here.

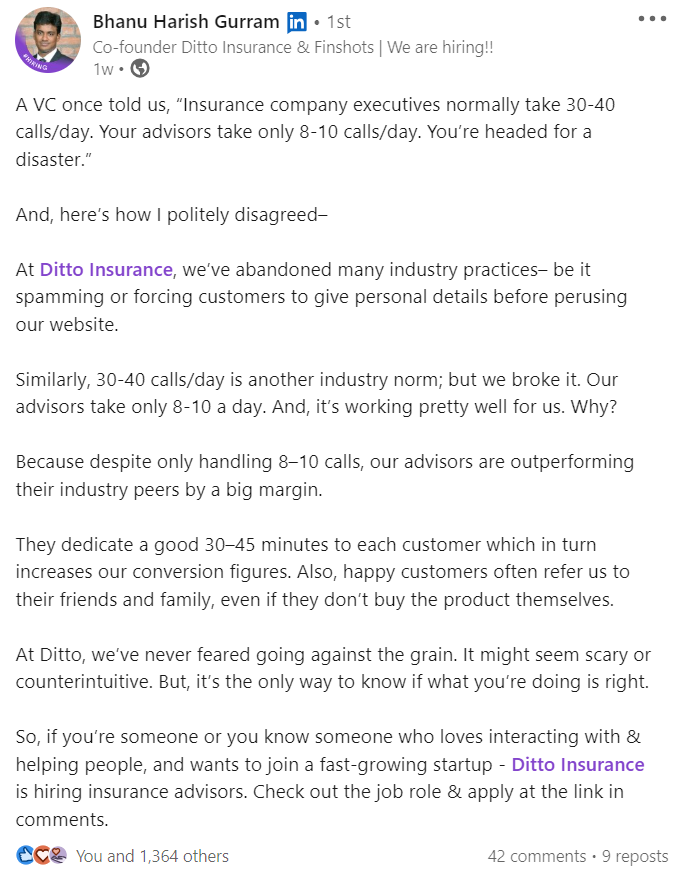

We are hiring!!!

Our team at Ditto (by Finshots) is looking to recruit 'Insurance Advisors'. If you crave an exhilarating journey that challenges you, rewards your drive, and gives you the platform to build exciting initiatives, this is the perfect opportunity for you. Apply now.