🍳Neglected heritage, drinkable seawater, and more...

Hey folks!

Earth might be known as the ‘blue planet’ because nearly 70% of its surface is water, but most of it isn’t fit for drinking. Oceans and seas make up 97% of all water — far too salty to drink, farm with, or use directly.

Well… what if we could make all that seawater usable?

That’s where desalination comes in: removing salt from seawater to get freshwater. In theory, it solves everything.

But here’s the catch: it’s expensive.

Think about your kitchen water purifier. It works beautifully when the input is river water or treated freshwater. But ask it to handle seawater and the energy costs would spike, the membranes would clog, and the filters would wear out within days.

Now scale that up to an entire town, and desalination becomes a money pit — high-pressure pumps, RO membranes, electricity bills, and constant maintenance. Salt damages everything it touches. In regions with extremely high salinity, the equipment may not even work reliably.

So yes, desalination works, but not without dehydrating your wallet first!

And that’s where IIT-Bombay and Monash University’s research comes in.

They’ve created a highly efficient, two-faced Janus film, officially called NCF@PH. So what does it do exactly?

Traditional systems rely on reverse osmosis, forcing seawater through a membrane using high pressure. And as salinity increases, so do pressure and costs. Which is why the researchers wanted something that doesn’t use pressure at all.

Their solution is a solar-powered system called SunSpring. This engineered material produces 18 litres of freshwater per square meter everyday, more than 2 times that of regular systems which make about 7 litres of water per square meter. It does this by having 2 faces — a sun facing side that captures sunlight efficiently, and a water facing side that lets the water vapour pass through it.

There’s another clever detail. Traditional solar stills use the same glass surface to admit sunlight and condense vapour. Once droplets form, they block light and reduce heating.

SunSpring avoids this by separating the jobs. Evaporation happens at the film; condensation happens on a Peltier cooler — a device that becomes cold when powered. This keeps the glass clear and the heating uninterrupted.

Since this is still a prototype, Professor Subramaniam Chandramouli of IIT-Bombay says it costs three times as much as a regular RO system. But once production goes factory level, it should bring prices down. So for the time being, it’s being deployed where it’s needed most: at a school where the children can get 300 litres of pure water per day. And if all goes well, we might even see a pilot plant where it can shine best: Rann of Kutch, one of the most saline regions in India. Interesting, isn’t it?

Here’s a soundtrack to put you in the mood 🎵

i wrote you a song by Tanmay Arora

You can thank our reader, Simran Verma, for this beautiful rec!

Ready to roll?

What caught our eye this week 👀

Why does India neglect its lesser known heritage?

What’s common between George Orwell and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee?

You could say they were both celebrated writers. And you’d be absolutely right. But there’s something else too. They were born in the British Bengal Presidency. And the homes where they spent small but significant slices of their lives are falling apart today, despite supposedly being under government care as heritage sites.

Let’s start with Orwell. Born Eric Arthur Blair in Motihari, in Bihar’s East Champaran district, he spent just about a year there before his mother took him and his sister back to England. His father, a British officer, worked in the Opium Department during colonial rule. And while the birthplace of the man who wrote Animal Farm and 1984 should ideally be something Bihar proudly preserves, the reality is sadly the opposite. The building’s roof has caved in. Birds, insects, and snakes, everyone seems to have claimed their own corner. Cows and pigs stroll in whenever they please, and the whole place looks eerily like, well, an actual animal farm. Irony just writes itself sometimes.

Most people in Bihar barely know Orwell existed, let alone that he shaped modern English literature. And the state government, despite bearing responsibility for its upkeep, simply does not have the time, money, or attention to spare. It’s just another forgotten structure in a state grappling with poverty, unemployment, and a broken education system.

The other house that recently made headlines is in West Bengal — Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s ancestral home in Naihati, where he wrote Vande Mataram, a composition that went on to become the national song. It’s supposed to be preserved by the state government. Yet neglect shows up everywhere. Peeling paint, seepage-stained walls, dim lighting and no proper air conditioning to protect artifacts. Ironically again, India marked 150 years of Vande Mataram just a few weeks ago, celebrating the very legacy this house represents.

Now, here’s the thing. Technically, the state government insists that the house isn’t in ruins, and there’s a political disagreement around this between the Centre and the State. But that’s not Finshots’ lane, so we’ll park that conversation aside.

Instead, what’s really got us thinking is this. Why do heritage sites remain neglected even after being declared heritage sites, and even when they could draw tourism?

One big reason is funding. Look, India’s heritage conservation is chronically under financed. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which looks after 3,695 centrally protected monuments, got just ₹1,270 crore for FY26. That’s only about 0.08% of total government expenditure. Break it down and it’s roughly ₹34.5 lakh a year per monument. That isn’t nearly enough to restore, secure, maintain, and modernise thousands of old structures.

Between 2010 and 2023, ASI’s budget barely moved in the ₹1,200-₹1,500 crore range, even as inflation rose and buildings aged. Meanwhile, the Culture Ministry budget is spread thin across dozens of museums, academies, libraries, and cultural institutions.

So if centrally protected monuments are stretched this thin, imagine what happens to state-level heritage buildings. Their archaeology departments rely on fragmented funding, irregular grants, and political priorities. If a site doesn’t promise tourism potential, funding often dries up before it arrives.

Then there’s the classic maze of bureaucracy. Multiple agencies, paperwork loops, and endless approvals drag processes out for years. A CAG report once found that 70% of ASI monuments were in “neglected condition” largely because of administrative delays. And the same slowdown plays out across states. Even Bankim Chatterjee’s house took years to simply get heritage status, because officials had to prove that the structure held “architectural value”, even though history itself was the real value.

And of course, manpower. In Bihar, officials admit that Orwell’s house isn’t a priority right now because they have too many other projects underway and too few people to execute them. Naturally, sites generating more tourist footfall get faster attention because preservation also needs revenues to justify itself.

Like Orwell wrote, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” Turns out, heritage sites follow the same rulebook.

So yeah, while the political blame games rage on and budgets stretch thinner each year, these quiet old homes are left to weather time on their own. They wait silently, hoping someone will notice before it’s too late. Whether they’ll eventually get a second life is something we’ll just have to wait and see.

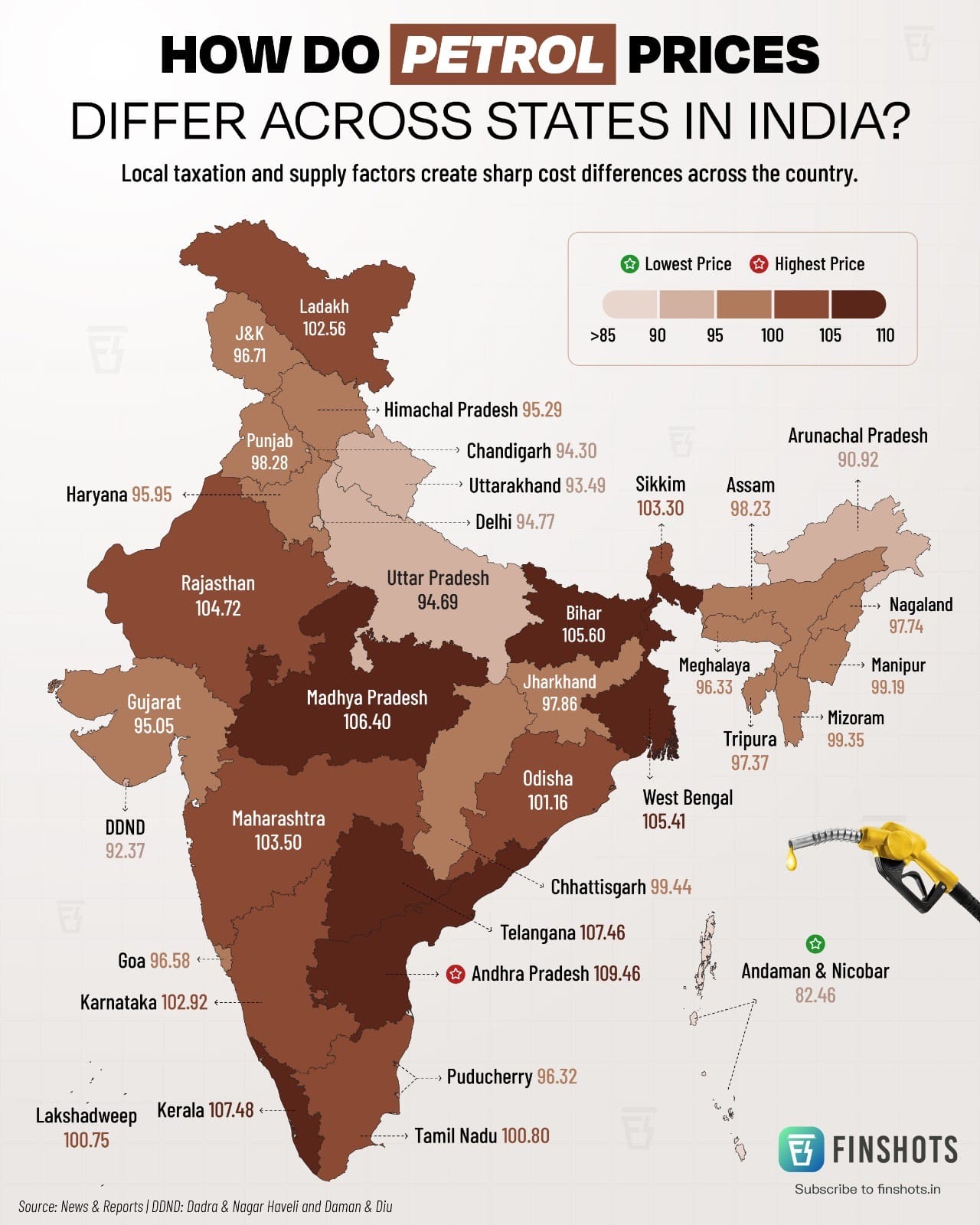

Infographic 📊

Readers Recommend 🗒️

This week, our reader, Neeraj Talagani, recommends reading Build, Don’t Talk by Raj Shamani.

The book dives into all the things we were never really taught in school like how to sell, build relationships, negotiate, manage our mental health, network effectively, and handle personal finance. In short, the real-world skills we need to succeed as we grow.

Neeraj tells us the topics feel incredibly relatable too. Thanks for the recommendation, Neeraj!

That’s it from us this week. We’ll see you next Sunday!

Until then, send us your book, music, business movies, documentaries or podcast recommendations. We’ll feature them in the newsletter! Also, don’t forget to tell us what you thought of today's edition. Just hit reply to this email (or if you’re reading this on the web, drop us a message at morning@finshots.in).

🖖🏽

Don’t forget to share this edition on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.