Is China’s Trojan Horse dead?

In today's Finshots we talk about China's troubles with the Belt and Road Initiative

But before we get to today’s story, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s going on in the world of business and finance - why aren’t you subscribed yet? We’ll send you this newsletter every morning with crisp financial insights straight to your inbox. Subscribe now!

If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story. :)

The Story

$30 billion — That’s what Pakistan owes China.

$5 billion — That’s Sri Lanka’s debt to China.

And while the numbers may vary depending on who’s doing the calculation, there’s consensus on one thing — India’s neighbours are knee-deep in debt and they all owe money to China. And it’s not just them. Atleast 97 other countries are indebted to the Red Dragon.

But how did this happen?

Well, through something called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). But before we get to BRI, we have to rewind a bit — to 130 BCE. The Han Dynasty ruled China and traders were looking to sell their wares beyond the borders. They wanted to move silk, tea and spices westwards to Europe and meet the considerable demand for these exotic goods. Slowly, a network of roads emerged from nothing. Routes that stretched for nearly 6,500 kilometres across all kinds of terrains — deserts, mountains, and seas. It was quite phenomenal and in a way, it was a symbol of Chinese influence.

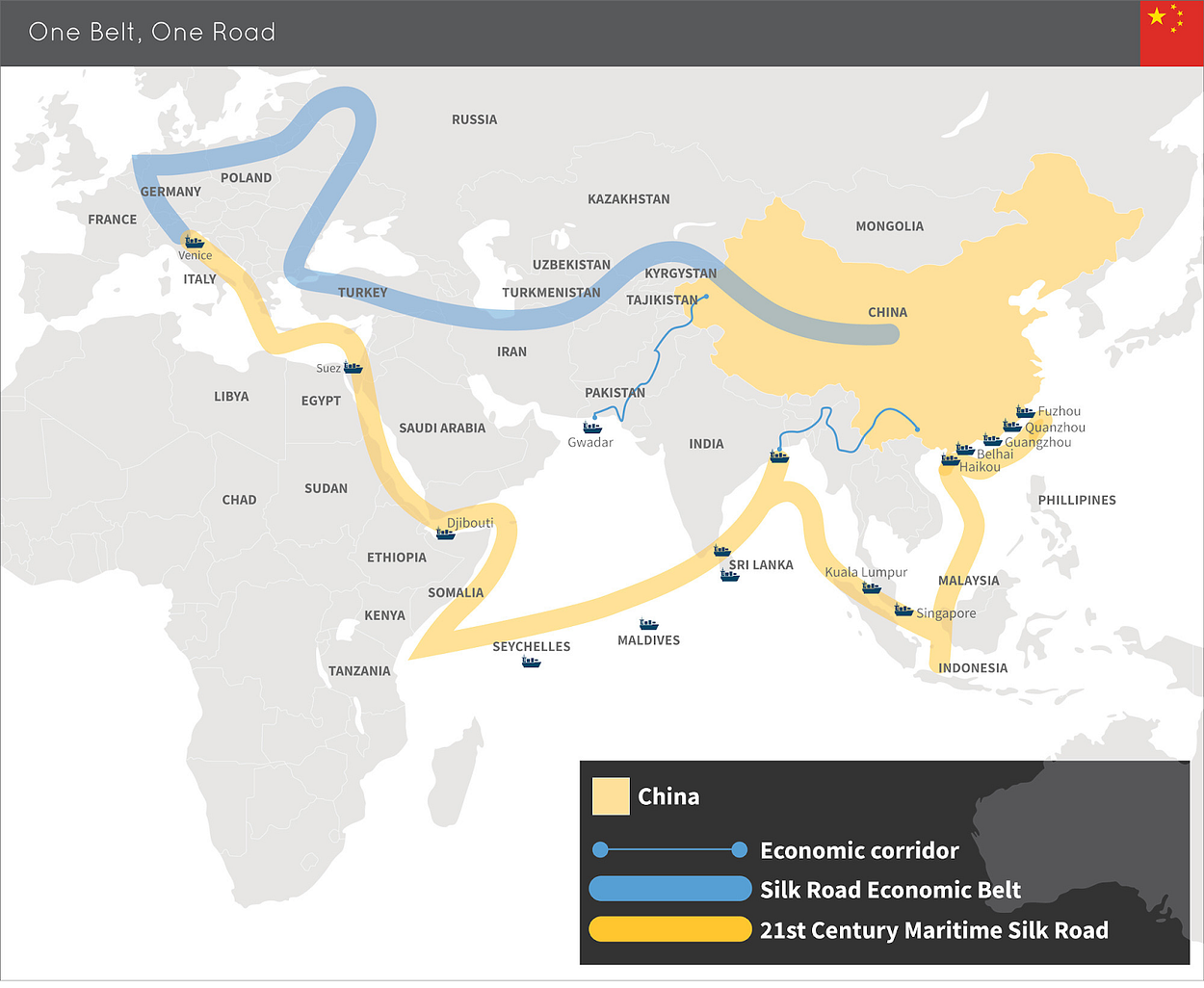

It was called the Silk Road. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire would close off the routes and cease all trade with the West. But in 2013, China decided to revive these long-lost trading routes and improve on them. They called it the Belt and Road Initiative — long winding road and sea routes connecting China with Europe, Asia, and Africa. Just like in the old times.

And here’s how they went about building it.

China loaned large sums of money to countries to help build the necessary infrastructure. And they developed strong trade relationships in the process. By the end of 2021, the total investments had reached a staggering $850 billion.

Source: World Economic Forum/Lowy Institute

And for countries looking to access cheap capital, this was a godsend.

Take Africa for instance. While international bodies like OECD-DAC provide aid to low-income nations, they usually reserve it for social projects like health and education. So when it comes to infrastructure, they need to look elsewhere. And that’s where China comes in.

Now China is a smart lender. A study of over 100 loan contracts revealed quite savvy terms and conditions. For instance, China could demand repayment if the debtor country changed its economic policies significantly. In other cases, they’d ask countries to deposit collateral in a special offshore account. So in the event of a default, China could just liquidate the collateral and make good on their principal without going to court.

But the pace at which they kept ramping up the program began worrying outside observers.

The US called the BRI a Trojan horse. Others like Indian international security specialist Brahma Chellaney termed it “Debt-trap diplomacy”. The argument being — China would trap unsuspecting countries in a spiral of debt and take over critical infrastructure in the process — ports and such.

Like Laos — when it ceded control of a power grid for 25 years to a Chinese-owned company in return for some debt relief. Or Angola — when it had to redirect most of its oil exports to China when it failed to repay its debt. Even Sri Lanka ceded control of the Hambantota Port for 99 years to China after the country ran into financial troubles.

So you could argue that this is a Chinese conspiracy to ensnare other nations.

But wait…what if it’s not entirely true?

According to Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire, professors at Johns Hopkins University and Harvard Business School, this Debt-trap narrative is a fallacy.

In fact, they point to Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port itself. See, the country first approached the US and India in 2007 to help set it up. Both said no. It was only then a Chinese construction company entered the fray. But the project didn’t take off as expected and Sri Lanka needed money. Finally, they offered it out on lease and invited bids. Only two Chinese companies came forward. Others could’ve bid but no one else did. A 99-year lease was signed and Sri Lanka put the $1.2 billion into its forex reserves.

So it wasn’t as if the Chinese were planning this all along.

And Sri Lanka didn’t default on its obligations either. It was just a narrative that gained popularity.

Also, according to research by AidData, Chinese lenders haven’t actually “seized” assets. In many cases, they just restructured the terms of the loans. After all, they’re businessmen who want their money back. What will they do with mines and ports?

But here’s the thing…at the end of it all, maybe the BRI isn’t actually going the way China planned?

Countries like Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, and Zambia are staring at possible defaults that will hurt Chinese lenders even more. And at least 35% of projects under BRI seem to be going nowhere in terms of implementation.

It’s a problem that Nikkei Asia highlighted last month. Their journalists travelled across the New Silk Route — to the Gwadar Port in Pakistan, to Sihanoukville in Cambodia, and to Kuala Lampur in Malaysia. They found that ports are as silent as a graveyard, unfinished buildings pepper the regions, countries are cancelling BRI projects, and citizens of various nations are getting increasingly disenchanted with China’s “aid”.

And that disenchantment could be the nail in the coffin for China’s BRI ambitions. The new Silk Route might well be dead.

And even if there was a grand conspiracy to seize effective control of assets across the world, well, it might just fall flat on its face.

Until then…

If you learnt something new, why not share it with your friends? Share this story on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Twitter

Ditto Insights: The simplest way to save on taxes

Nobody likes to pay taxes and if you felt like you paid way too much in taxes this year, you should definitely consider buying insurance. You can save a lot of money this way and we will explain how:

1. Health Insurance:

Under section 80D, you can reduce your taxable income by up to ₹1 lakh depending on your age.

Let’s say you’re under 60 and paying premiums for yourself and your family (spouse & children). In this case, you can avail up to ₹25000 in tax deductions. Now add your parents to this and you can save even more. How much? you ask.

If they’re under 60, you can avail deductions of upto ₹50000.

Over 60, and you can claim ₹75000 in deductions.

In case both you and your parents are 60+, you can reduce your taxable income by ₹1 lakh.

2. Term Insurance

Term insurance is quite literally a lifesaver. But you can also claim deductions of up to ₹1.5 lakhs under Section 80C.

3. TDS:

If you're a working professional, you can boost your in-hand salary by declaring your term & health insurance premiums to your HR. This reduces your taxable income or "TDS / Tax Deducted at Source".

And if you want to buy Health or Term Insurance, the easiest way to do it is through Ditto.

1. Just head to our website — Link here

2. Click on “Book a FREE call”

3. Select “Health” or “Term Insurance”

4. Choose the date & time as per your convenience and RELAX!

Our advisors will take it from there!