🍳IPL’s strange year, India's avocado obsession, and more...

Hey folks!

It’s Sunday, which usually means good food, slow cooking, and the inner MasterChef in many of us finally getting a chance to shine. Grills come out, ovens warm up, and pans start sizzling. And speaking of Sunday feasts, there’s one oval, green fruit that has quietly made its way into Indian kitchens. We’re talking about the humble avocado 🥑.

But the strange part is how long it stayed invisible.

About a decade ago, I remember going to a regular juice shop and asking for two butter fruit shakes for me and my father. The fruit was so dense that even half of it was enough to make two thick milkshakes. Butter fruit, as it was popularly known back then, is what the rest of the world calls the avocado.

But here’s the thing. Avocados aren’t new to India at all. In fact, they’ve been around for well over a century, despite originating in Central America. As early as the mid-1800s, a correspondent from the The Times of India wrote about the fruit, praising it as superior to many local varieties. When it found its way into the Hobson-Jobson dictionary, it was called the alligator pear. Missionaries later introduced it to hilly regions like Wayanad and Coorg, where families quietly grew it in their backyards.

Even spiritual figures took note. In 1935, the yogi Paramahansa Yogananda is believed to have recommended the fruit to Mahatma Gandhi during a visit to his ashram. Between then and now, avocados largely stayed small and, in the background, mangoes, apples and coconuts took centre stage in India’s fruit palate.

Commercial farming wasn’t seriously considered until the 2000s, and even then, production remained small and artisanal. That changed in 2021, when Westfalia Fruit, the world’s largest avocado supplier, entered the Indian market with Tanzanian avocados. Their aim was to push the fruit beyond niche consumption. And the timing couldn’t have been better.

India was in the middle of a social-media-fuelled health awakening. Suddenly, we were obsessing over protein, nutrients and healthy fats. And the avocado fit right in. Local production couldn’t keep up, forcing India to import nearly 90% of its avocados. And with fruits, imports usually mean two things: they’re exotic, and they’re expensive.

That’s why states like Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Sikkim and Madhya Pradesh have begun commercial avocado farming, driven largely by first-generation entrepreneurs. This December, we may even see the first harvest of home-grown Hass avocados — a potential turning point for the fruit’s premium pricing. And if you’re wondering why it’s taken this long, avocados need close to four years to mature from sapling to fruit.

But lower prices haven’t slowed creativity. India imported about 19,000 tonnes of avocados in 2025 — more than double the previous year. And instead of sticking to toast and smoothies, Indians have gone much further. From Haldiram’s experimenting with avocado-based sandwiches and chaat, to street vendors stuffing it into pani puri and chutneys (yes, avocado chutneys, we’re not judging 😬), the avocado revolution seems to be just getting started.

Here’s a soundtrack to put you in the mood 🎵

Cubbon Park by Derek & The Cats

You can thank our reader Akshay Naik for another great recommendation! What a lovely tribute to our very own Cubbon Park. We’re crying (with joy, of course)! 😊

What caught our eye this week 👀

Why IPL teams spent big even as valuations slipped

So here’s something interesting about this year’s IPL mini auction.

On the surface, it didn’t look like a big deal. Franchises spent about ₹215 crore to buy 77 players. That sounds modest, especially if you remember last year’s mega auction, where teams went wild and spent ₹639 crore.

But that’s because we’re comparing apples to oranges. A mega auction is a full reset, where teams rebuild almost their entire squad from scratch with a large budget. A mini auction, on the other hand, is more of a top-up where teams keep their core and spend only to fill a few specific gaps.

And once you look at it that way, something interesting pops out.

Because despite being a mini auction, it was still the second-highest spend ever of its kind. And more importantly, it was packed with records.

Cameron Green became the most expensive overseas player in IPL history, with Kolkata Knight Riders (KKR) paying ₹25.2 crore for him. That broke the previous record set by Mitchell Starc. Meanwhile, Chennai Super Kings (CSK) did something even more eyebrow-raising. They paid ₹14.20 crore each for Prashant Veer and Kartik Sharma — both uncapped players.

Quick context. Capped players are Indian cricketers who’ve already played for the national team, so they come with higher base prices. Uncapped players haven’t represented India yet, so their base prices are much lower. Which is why seeing uncapped players go for ₹14+ crore raised eyebrows across the board.

So yeah, franchises didn’t spend recklessly overall. But when they spotted players they really wanted, they didn’t hesitate.

And that’s where the contradiction kicks in.

Because while auction prices were climbing, the IPL’s overall valuation was falling.

According to the D&P Advisory valuation reports, the league’s valuation fell from around ₹92,500 crore in 2023 to about ₹76,100 crore in 2025. That drop wasn’t random.

Two things changed.

First, media rights. In 2024, the Disney+ Hotstar and JioCinema merger meant that media rights got consolidated under JioStar. The wild bidding wars between broadcasters, which used to once push rights prices to crazy levels, simply stopped. And one dominant buyer means fewer fireworks.

Second, sponsorship money dried up. The government’s Real Money Gaming ban in 2025 wiped out roughly ₹1,500–2,000 crore a year. Before that, gaming brands had been everywhere — on jerseys, ads, even title sponsorships. And then they vanished almost overnight.

So the league got smaller.

Which makes the auction behaviour even more fascinating. Why spend big when the ecosystem is under pressure?

Because maybe, right now, winning matters more than ever.

Franchises seem to be moving away from easy gaming money and chasing steadier sponsors like auto companies, fintech firms, and healthcare brands. But these sponsors don’t just throw money around. They pay for teams that win, stay visible late into the season, and keep fans engaged.

And the punishment for losing has become brutal. In the last valuation cycle, for instance, Rajasthan Royals saw their valuation drop by about 35%. Sunrisers Hyderabad fell roughly 34%. This shows that there’s very little mercy for underperformers in a shrinking ecosystem.

So franchises have made a clear bet. If the IPL isn’t growing right now, performance on the field is the only real insurance (wink wink 😉). Winning protects brand value, keeps sponsors interested, and buys time.

And maybe that’s what this auction was really about.

Teams weren’t just buying players. They were buying relevance. And hoping that stronger squads would mean deeper playoff runs, bigger audiences, and stronger bargaining power when sponsors come knocking again.

And maybe they’re also betting on the future by believing that one or more of three things will eventually play out:

- That digital viewership will still convert into premium sponsorship money.

- That global streaming giants like Netflix, Amazon, or Apple will one day shake up media rights bidding again, or

- That fresh, uncapped Indian talent could build new fan loyalty and partly fill the revenue hole left by gaming sponsors.

So yeah, the paradox is real. The IPL’s overall value has shrunk. But player salaries are soaring.

And maybe that’s because franchises believe one simple thing: if you want growth later, you have to win now. What do you think?

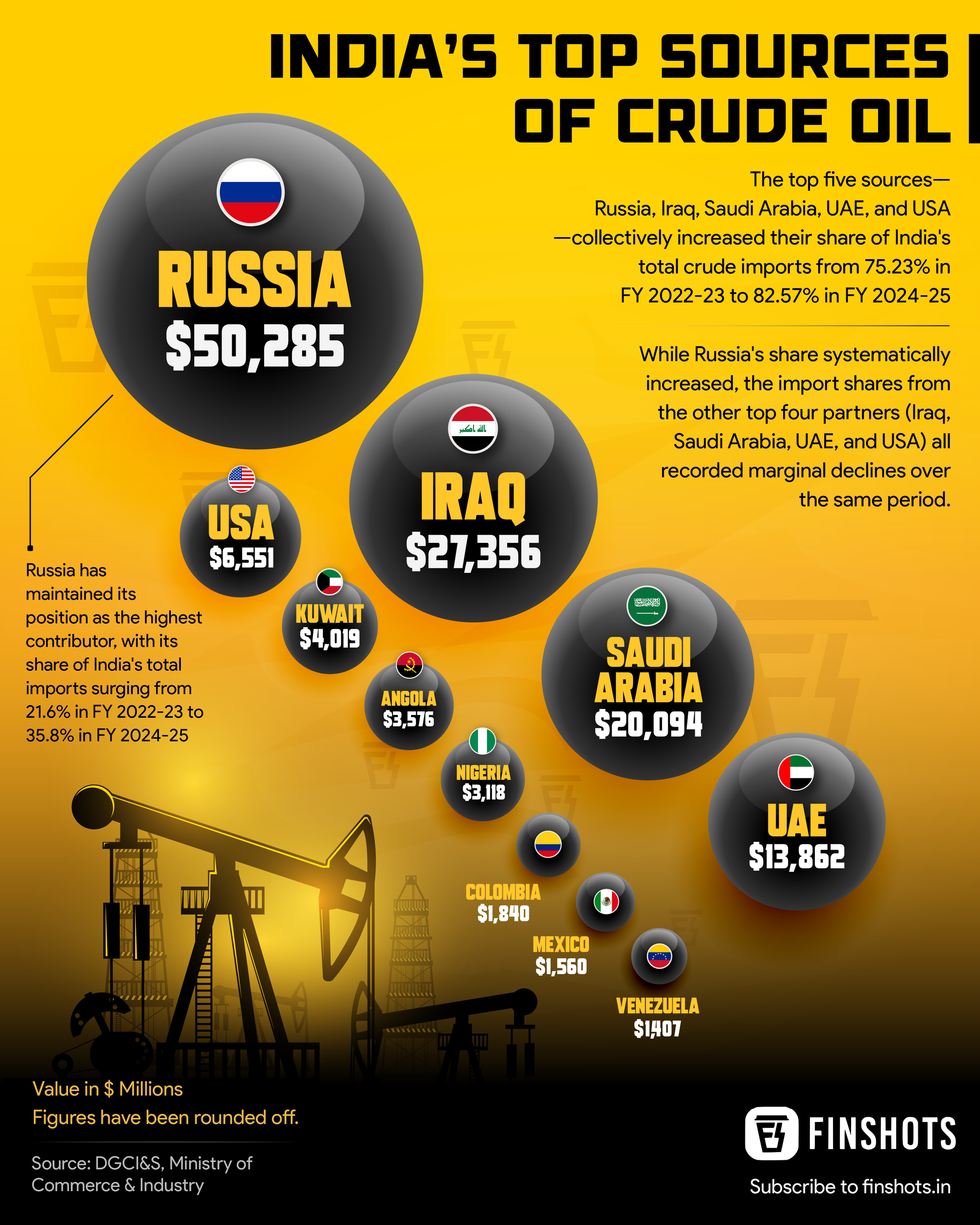

Infographic 📊

Readers Recommend 🗒️

This week, our friend Rishabh Jain is back with another recommendation. This time, it’s a book called An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India by Shashi Tharoor.

Rishabh says, “This powerful work examines the economic, political, and social devastation caused by British colonial rule in India. Tharoor dismantles myths about the Raj’s “benefits” and shows how exploitation shaped India’s trajectory. For business and finance professionals, it offers critical lessons on the long-term impact of economic policies, resource extraction, and systemic inequality — issues that still resonate in global trade and development today.”

Thanks for the recommendation, Rishabh!

That’s it from us this week. We’ll see you next Sunday!

Until then, send us your book, music, business movies, documentaries or podcast recommendations. We’ll feature them in the newsletter! Also, don’t forget to tell us what you thought of today's edition. Just hit reply to this email (or if you’re reading this on the web, drop us a message at morning@finshots.in).

🖖🏽

Don’t forget to share this edition on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.