France is in a debt dilemma

In today’s Finshots, we tell you how France spiralled into extreme debt and why its proposed solution might just be another problem in disguise.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

There are plenty of ways to measure a country’s economic health. One of them is the debt-to-GDP ratio. Simply put, this ratio compares a nation’s public debt to its gross domestic product (GDP) or the total value of all the goods and services it produces. Think of it as a measure of how well a country can manage and repay its debt. The higher the ratio, the harder it becomes for a country to manage its debt because it signals a greater risk of defaulting on that debt, which can lead to financial panic at home and abroad. And this is exactly the kind of situation unfolding in France.

France’s debt-to-GDP ratio recently soared to about 110%.1 This means that the country owes roughly €3.2 trillion (around $3.5 trillion) to banks and investors. And that’s quite a problem because the World Population Review suggests that a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 77% for long periods isn’t great for economic growth.2 Every percentage point of debt above this level could stifle economic growth by about 1.7%.

Now, not every country is in the same boat. Take Japan, for instance. Its debt-to-GDP ratio is over 250%. But Japan’s risk of default is low because it owes most of its debt to its own citizens.

France, however, is dealing with a different beast as nearly half of its debt is owed to foreign investors.3 And given its sluggish economic growth, confidence in France’s ability to repay its debt is waning. That’s a pretty precarious situation, and it’s clear that France needs a plan.

But before we jump into how France aims to tackle its debt problem, let’s rewind a bit and see how it got here.

The story begins with the global financial crisis of 2008, which popped the overly hyped property market bubble.4 During the boom, everyone was building homes left and right, fuelled by cheap debt. People and construction companies borrowed money, even when their credit histories were shaky or they couldn’t really afford it. But when the bubble burst, property values tanked, and countries around the world, including France, felt the impact. As revenue from real estate dried up, the French government had to step in and inject funds to support the struggling economy.

Fast forward about a decade, and the pandemic hit. Just like many other nations, France pumped money into its economy for social protection. In 2022, the French government spent more than 58% of its GDP on rescue packages, which was 9% more than the European Union’s (EU) average.5 And that included reducing taxes too. Naturally, revenues declined and debt increased.

Then, there was the Russia-Ukraine war, which drove energy prices through the roof, particularly in Europe. Before the invasion, Russia was the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, with Europe as its biggest customer. But when the EU imposed sanctions on Russia to discourage war, its countries scrambled to find alternatives. This left many, including France, struggling to reduce their dependence on Russian oil and gas. Energy prices skyrocketed and household electricity costs jumped by at least 60% since 2021.6 To ease the burden on consumers, the French government partly delayed price hikes and reduced electricity taxes. This kind of subsidised electricity left another hole in revenues.

Season this with some of the tax cuts implemented by Emmanuel Macron’s government to win votes since he became president in 2017, and you’ve got the perfect recipe for disaster resulting in a €15 billion loss in revenue.7

The end result was that France’s budget deficit — the gap between what the government spends and what it earns — ballooned to nearly 6% of its GDP, way above the EU’s 3% target. This has raised red flags for investors, who are now demanding higher premiums to lend money to France due to the increased risk. At the same time, France’s sovereign credit rating, essentially the trust that credit rating agencies have in the country’s ability to repay its debt, is slipping. All of this means higher interest costs for France, putting immense pressure on the government to restore its finances and aim for that 3% target by 2027.

That’s a tricky situation because it leaves France with just two tough choices.

One, it could significantly reduce public spending by about €50 billion.8 But since massive spending cuts seem nearly impossible, the government’s focus has also turned to increasing taxes.

And that’s what France’s new Prime Minister Michel Barnier seems to be going with for now. He sort of has a new budget plan to save €40 billion and possibly raise €20 billion more in revenues through new temporary taxes.9 These taxes would include a tax on superprofits of companies with a turnover of more than €1 billion and increase taxes on wealthy individuals. And with this he thinks that France could get back on track by 2029.

But there’s a problem with this solution. At 45%, France already has one of the highest combined tax rates in the world, including income taxes and mandatory contributions towards social security schemes. While the global average hovers around 40%. It’s almost like French citizens cannot afford to pay any more taxes.

And if the government decides to shift more of this burden onto wealthy individuals and high-earning companies, it could backfire. That’s because over the years, there has been a noticeable uptick in people wanting to move to countries like Spain and Switzerland.10 And if France raises taxes too much, we could see more folks packing their bags for greener pastures.

But that’s not all. As part of its plan to tax the wealthy, France is considering raising taxes on air passengers.11 This could make travelling to and within France more expensive, potentially dampening tourism. Plus, higher taxes on flights could hit the aviation industry hard, which is already working to shift from fossil fuels to sustainable aviation fuels.

So, while France is scrambling for solutions, the proposed fixes come with their own set of challenges.

Does that leave France with really no way to tackle this dilemma, you ask?

Actually, there might be a solution. Instead of hiking taxes, France could broaden its tax base by closing loopholes in its tax system. Take short-term rentals like Airbnb, for example. They currently benefit from a tax loophole that allows them to pay lower taxes, treating them like bed-and-breakfast services. This means that they save nearly 70% of the taxes they pay on their rental income — something hotels can’t do.12 Plus, this situation is contributing to a housing shortage in France, which has drawn a lot of criticism.

Reducing those tax savings from 70% to just 30% for short-term rentals and addressing other similar tax loopholes could create a fairer tax system and boost France’s revenue.

So yeah, France is walking a tightrope. And we’ll have to wait until the country’s final 2025 budget, scheduled for tomorrow, to see if it can really balance its shaky debt.

Until then, it looks like France has its work cut out.

Don't forget to share this story on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X.

📢 Ready for even more simplified updates? Dive into Finshots TV, our YouTube channel, where we break down the latest in business and finance into easy-to-understand videos — just like our newsletter, but with visuals!

Don’t miss out. Click here to hit that subscribe button and join the Finshots community today!

Story Sources: DW [1], World Population Review [2], Reuters [3], World Economic Forum [4] [6], Financial Times [5], The New York Times [7], Le Monde [8], Tax Foundation [9], The Economic Times [10], Bloomberg [11], Euro News [12]

A message from one of our customers

Nearly 83% of Indian millennials don’t have term life insurance!!!

The reason?

Well, some think it’s too expensive. Others haven’t even heard of it. And the rest fear spam calls and the misselling of insurance products.

But a term policy is crucial for nearly every Indian household. When you buy a term insurance product, you pay a small fee every year to protect your downside.

And in the event of your passing, the insurance company pays out a large sum of money to your family or your loved ones. In fact, if you’re young, you can get a policy with 1 Cr+ cover at a nominal premium of just 10k a year.

But who can you trust with buying a term plan?

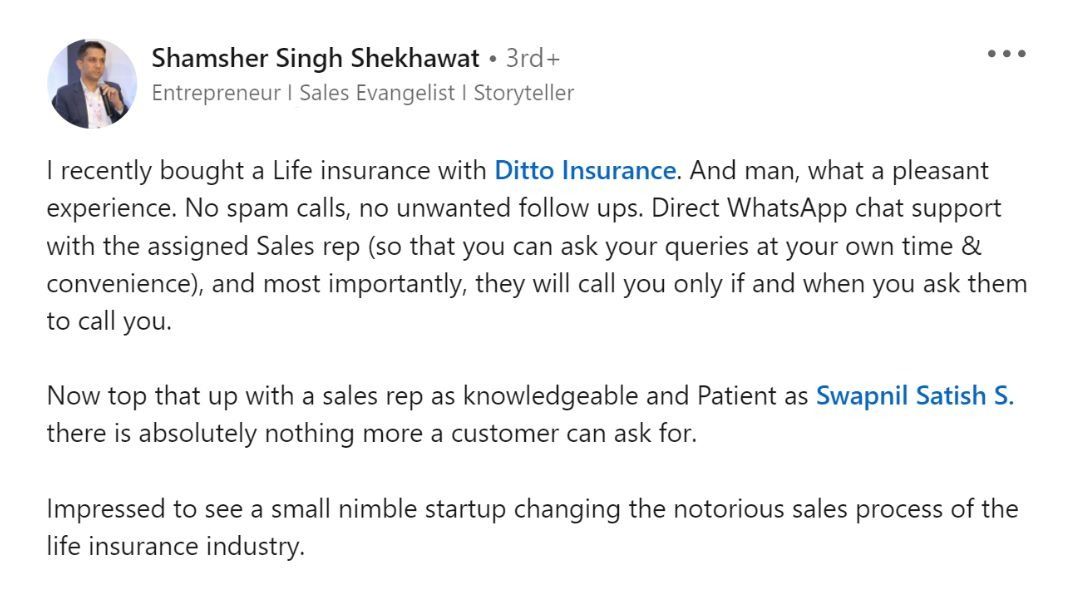

Well, Shamsher - the gentleman who left the above review - spoke to Ditto.

Ditto offered him:

- Spam-free advice

- 100% Free consultation

- Direct WhatsApp support for any urgent requirements

You too can talk to Ditto’s advisors now, by clicking the link here