Citibank's $900 Million Fiasco

A few months back, Citibank accidentally transferred nearly $900 million dollars to a group of lenders. And now, a New York Court has ruled that the lenders are under no obligation to return the money. So in today's Finshots, we discuss the greatest blunder of 2020.

The Story

Revlon is a multinational American Cosmetics company. And in 2016, they acquired Elizabeth Arden, another cosmetic giant. The deal was expensive and it featured a $1.8 billion loan. Many companies were involved in the financing arrangement. There was Brigade Capital, a hedge fund. There was Allstate, an Investment Management Company. There was “New Generation Advisors”, a fund based out of Elm Street. And there were a few others.

Citibank meanwhile served as the administrative agent for the loan. It was incumbent on them to collect payments from Revlon and transfer it to the lenders whenever the interest was due. And they did a swell job for the most part. However, Revlon had been struggling since the deal materialized. Most lenders were expecting the company to default on its obligations. And as the pandemic started wreaking havoc, these fears only amplified.

Which is why it came as a surprise when on 11th August 2020, Revlon prepaid the loan in full with the accrued interest. That was a total of ~$900 million paid in full, all at once, seemingly out of the blue.

But soon enough, it became apparent there was an error. Citibank, the administrator was only expected to send interest payments to the tune of $7.8 million on behalf of Revlon. Instead, they sent the $7.8 million and a cool $894 million on top. They had inadvertently sent the principal from their own account.

So how on earth did this happen?

Well, maybe we could start with the Indian connection. It just so happens that several members involved in the wire transfer happened to be employees of Wipro. These people worked exclusively on Citibank matters and maintained Citibank email addresses. Now the transaction might have seemed rather straightforward when we explained it earlier. But moving funds internally using a sophisticated banking solution (called Flexcube) is anything but simple. To successfully execute the transaction, the employees had to move the interest to the lender’s account, but also simultaneously move the principal to an internal Citibank account, called the wash account.

Don’t ask why! It’s complicated.

The transaction was also subject to CitiBank’s “six-eye” approval procedure, which requires three people to review and approve a transaction before it is executed. Under this procedure, (1) the “maker”, a Wipro Employee, first inputs the payment information into Flexcube; (2) the “checker” — Another Wipro employee then reviews and verifies the transaction; and finally (3) the “approver” — a Citibank senior manager serves as a final check on the maker and checker’s work.

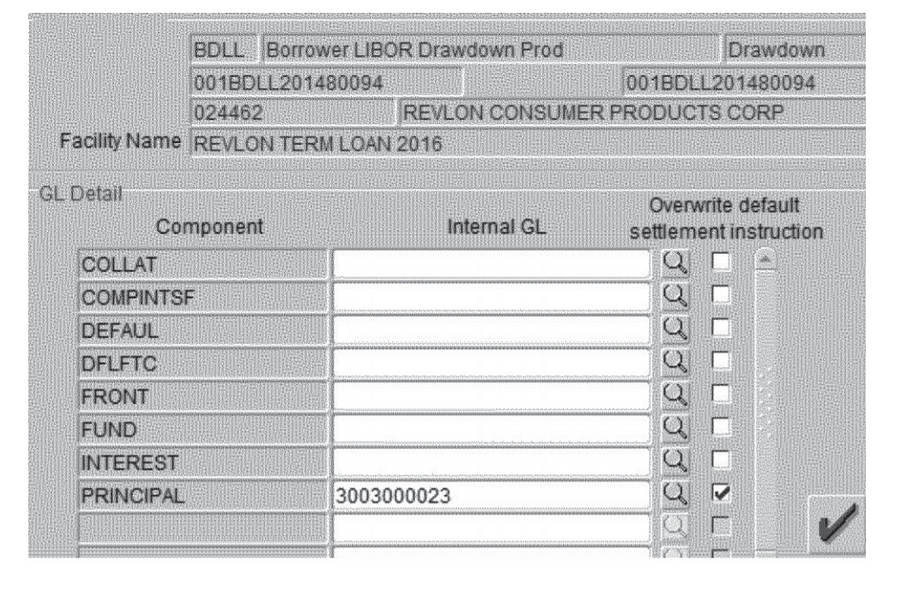

And when entering the payment information, the employees were presented with a menu and several checking boxes. Remember, they were only supposed to send the interest due. The principal meanwhile was expected to be diverted back to the Citibank’s wash account. And in order to prevent the principal from moving out of the bank, the employees had to check three boxes named “FRONT, FUND and PRINCIPAL”

And as the court document notes — Notwithstanding these instructions, all three employees incorrectly believed that you could suppress the principal payment solely by checking the “PRINCIPAL” field alone. All “six eyes” failed to notice the error.

In fact, the next day when they were made aware of the $900 million hole, they believed this was a tech issue at first. The Citibank official involved in the transfer even shot out an email to members of his team —

“Urgent Wash Account Does not Work. Flexcube is not working properly, and it will send your payments out the door to lenders/borrowers. The wash account selection is not working”

It was only much later they realised this was in fact a human error.

Anyway, Citibank demanded the lenders to pay back the money, since this was an obvious error. But since most lenders weren’t very cooperative, the matter went to court. At the time we wrote an elaborate exposition on why Citibank might just get their money back. We talked about the principle of unjust enrichment.

In contract law, unjust enrichment happens when there’s an enrichment of one party at the expense of another in circumstances that the law sees as unjust. It can happen, for instance, when someone pays money to another individual under the mistaken belief that he/she is liable to pay the amount. And in the event, such a transaction does transpire, the law imposes an obligation upon the recipient to pay back the money in full.

The application of this principle is illustrated in a popular case from English Common Law — Kelly v Solari.

The matter was regarding a life insurance policy. Mr. Solari had passed away. His widow claimed £200 from the insurance provider upon his death. The claim was paid in full. But soon enough, the insurers found out that the policy had lapsed before the death of Mr. Solari. They realised they weren’t liable to pay because Mr. Solari had missed a premium instalment.

And the judges agreed. They noted —

Where money is paid to another under the influence of a mistake in circumstances where if the true facts had been known the money would not have been paid, an action lies to recover the money and it is against the conscience of the recipient to retain it.

Ergo, the lenders are obligated to pay back Citibank since this was a clear and obvious error. But there is an exception to this rule.

As the New York Court of Appeals explained: “When a beneficiary receives money to which it is entitled and has no knowledge that the money was erroneously wired, the beneficiary should not have to wonder whether it may retain the funds; rather, such a beneficiary should be able to consider the transfer of funds as a final and complete transaction, not subject to revocation.”

So in summary, because the lenders were owed this money and they had no reason to think the transfer was a clear and obvious error, they were entitled to keep it.

Wow, what a story. Citibank will obviously appeal. But in the meantime, if you know anyone who has been following this matter, don't forget to share all the juicy details. (Links to WhatsApp, Twitter and LinkedIn here)