The climate change report everybody should read

In today’s Finshots, we explain the most interesting bits from the latest climate change report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Also, tax season is just round the corner. And if you need good insurance advice, you know who to call, right?

Ditto - Text us on WhatsApp

Alright, on with the story now.

The Story

Do you want to read a 3,675-page report on climate change?

Okay, how about a 96-page report stuffed with the technicalities?

Maybe if you’re a busy policymaker, a 37-page high-level summary will suffice?

Let’s be honest, very few people are going to read this report. These things are usually drab, boring, littered with incomprehensible words and will likely put you to sleep in 5 minutes. But that being said, the IPCC report is likely going to be one of the most important documents of the 21st century.

So we tried to read parts of it (and a bunch of other research papers) to put together some interesting stuff for you — About “colonialism”, “maladaptation”, and “emerging diseases”.

3 things in just 3 minutes!

So let’s start with “colonialism”.

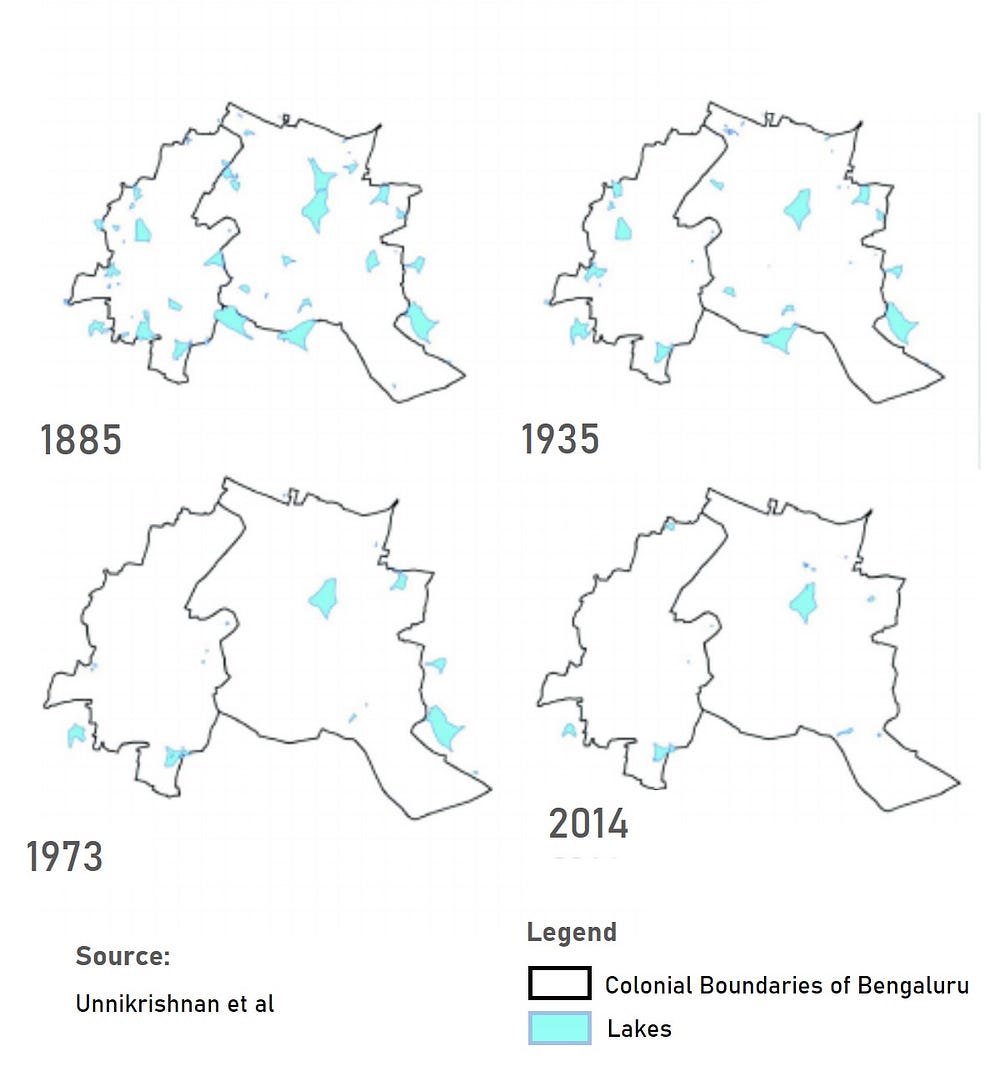

Picture Bengaluru in the 6th century. It was dry. It was arid and filled with thorny trees. Rulers at the time decided that they were going to change the terrain. Mould it from a semi-arid landscape to fertile land. They built tanks and streams to trap rainwater and help local communities thrive.

And they did.

By the time Kempe Gowda (the local chieftain) laid the foundation for what would become Bengaluru as we know it today, the landscape was already teeming with water bodies. This was the 15th century, but the visionary that he was, he decided to take it up a notch. We had more tanks, more lakes and more open wells than ever before.

Local communities thrived.

But then came the British. They loved the city. Only by now, the water wasn’t enough. The tanks weren’t cutting it anymore. And as the population grew, the British decided to set up piped networks to fetch water from places afar. They also cared about the “aesthetics.” So communities couldn’t fish or farm around lakes anymore and they had to migrate elsewhere. The lakes went dry. Settlements took over. And that brings us to post-independence India.

By now borewells and the piped network served most of Bengaluru’s water needs. And the old network of tanks that had once served multiple generations went out of use. Also, as the report notes — “More prolonged and costly water transfers took place in the post-colonial period, delivering water from the Cauvery river in a massive engineering project.”

A few decades pass by and we are now in the present.

As it stands today, Bengaluru is running out of groundwater. There’s an ongoing dispute over the sharing of River Cauvery. The city is still short on water. And the more sustainable alternatives (including the old tanks and lakes) have all but disappeared — thanks to colonialism and post-colonial policies. Or at least that’s what the report contends.

Then there’s “maladaptation”

What’s that, you ask?

Well, we adapt we make changes to our way of life when dealing with adverse events — climate change for instance. You could be planting a different crop when rainfall is low. You could be building out infrastructure to protect your community against floods. Or maybe you’re keeping away from the coastlines to protect the ecological niche.

You get the drift.

Now maladaptation is when these adaptations don’t work as intended. Or when they backfire rather spectacularly. Instead of protecting us from the vagaries of climate change, they bring us closer to harm.

Let’s take the example of Mumbai. We know that India’s city of dreams has largely been built on land reclaimed from the sea. It’s already altered the marine ecosystem and multiple reports have pointed out how Mumbai will bear the brunt of climate change. Think floods for instance.

Now, one way to deal with this is to build a floodwall along the sea. Even better, you build a road on top to deal with Mumbai’s insane traffic. The result is a high-speed expressway called the Mumbai coastal road. At a height of about 6m from sea level, it’s expected to counter the rising sea level.

However, as Nikhil Anand, a researcher of climate change points out — this may have unintended consequences. For instance, lower-lying regions like Prabhadevi, Tardeo and Warden Road, may see higher instances of flooding since they’re neighbouring the coastal road.

That is to say, to truly understand the impact of such adaptations, you need to first evaluate all the possible maladaptations. And unless we do it thoroughly, we may only be compounding an already existing problem.

And finally, “emerging diseases”

When Covid struck, everyone said the virus crossed over from a bat. But did it? We don’t know for sure. However, animals, birds and insects host a cocktail of bacteria and viruses that keep crossing over all the time. Most of them are harmless, but ever so often, something like Covid-19 pops and it changes the world forever.

But how is climate change related to all of this?

Well, as the report notes — “Ticks that carry the virus that causes tick-borne encephalitis have moved into northern subarctic regions of Asia and Europe. Viruses like dengue, chikungunya, and Japanese encephalitis are emerging in Nepal in hilly and mountainous areas. Novel outbreaks of Vibrio bacteria seafood poisoning are now being seen in Baltic States and Alaska where they were never documented before.”

The point is — Infectious diseases that were once relegated to localized areas are now spreading everywhere because the hosts (animals and birds) are also on the move thanks to climate change.

So yeah, the IPCC report is a bombshell and hopefully, we will have the opportunity to cover more items from the report over the next few months.

Until then…

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Twitter