An explainer on Pax Silica

In today’s Finshots, we tell you how China came to dominate the global critical mineral supply chain and the US’ Pax Silica initiative that it believes can counter it.

But before we begin, if you’re someone who loves to keep tabs on what’s happening in the world of business and finance, then hit subscribe if you haven’t already. If you’re already a subscriber or you’re reading this on the app, you can just go ahead and read the story.

The Story

In 1964, Chinese geologists made an interesting discovery. An iron ore mine near the city of Baotou also held the world’s largest rare-earth deposit.

At the time, rare earths weren’t fashionable. Most countries ignored them. But Chinese leaders didn’t. They saw rare earths as strategic, especially for defence and advanced materials. That’s why the country’s military wing quietly funded research into their uses.

But they also ran into a problem. Purifying rare earths was anything but easy. They weren’t “rare” because they were hard to find, but because they were hard to separate from one another. To solve this, the Chinese military turned to a chemist named Xu Guangxian. Working with his wife, Xu developed a cheap, scalable way to purify rare earths using basic chemicals and plastic tanks, essentially creating the first industrial “assembly line” for rare-earth separation.

The breakthrough changed everything. Large-scale refining became viable. Costs dropped. And because the technique was never patented, it spread rapidly across China.

From there, the state doubled down. Rare-earth mining and refining were folded into five-year plans, monitored closely, and reviewed often. China simply put its head down and built hundreds of refineries.

Meanwhile, the US and other countries made a very different choice. They saw rare earths as dirty, low-margin materials that weren’t worth the environmental damage. China on the other hand, accepted that pollution as the price of dominance. By 1986, that bet had paid off. It was the world’s largest producer of rare earths.

Another turning point came from the US. Engineers at General Motors’ Magnequench figured out how to turn rare earths into super-powerful magnets — essential for electric vehicles, wind turbines, smartphones and fighter jets.

But here’s the twist. GM wanted to secure approval for automotive production lines in Shanghai. So it sold Magnequench to investors that included Chinese firms linked to influential political families. The deal worked for GM. But it also meant that Chinese companies now owned critical, US-developed magnet technology and the ability to manufacture it at scale. So even if China didn’t invent magnet tech, it bought it. And then it scaled it.

Add cheap labour and low production costs to this mix, and you’ll see why China began using its dominance to influence global prices of rare earths and other critical minerals.

Sidebar: Rare earths are a specific subset of critical minerals, crucial for defence, automobiles and electronics. But the broader group of critical minerals also includes materials like lithium, cobalt and nickel, which have become essential for today’s tech advances, from batteries and clean energy to electric vehicles, chips and the computing power behind AI.

But because China was able to use its scale, it overproduced, drove prices down, made Western projects uneconomic, and scaled up even further as competitors in other countries shut shop. Even companies in emerging markets that tried to invest in critical minerals found themselves squeezed by collapsing margins and uncertain buyers. Once that happened, China could tighten supply and regain pricing power.

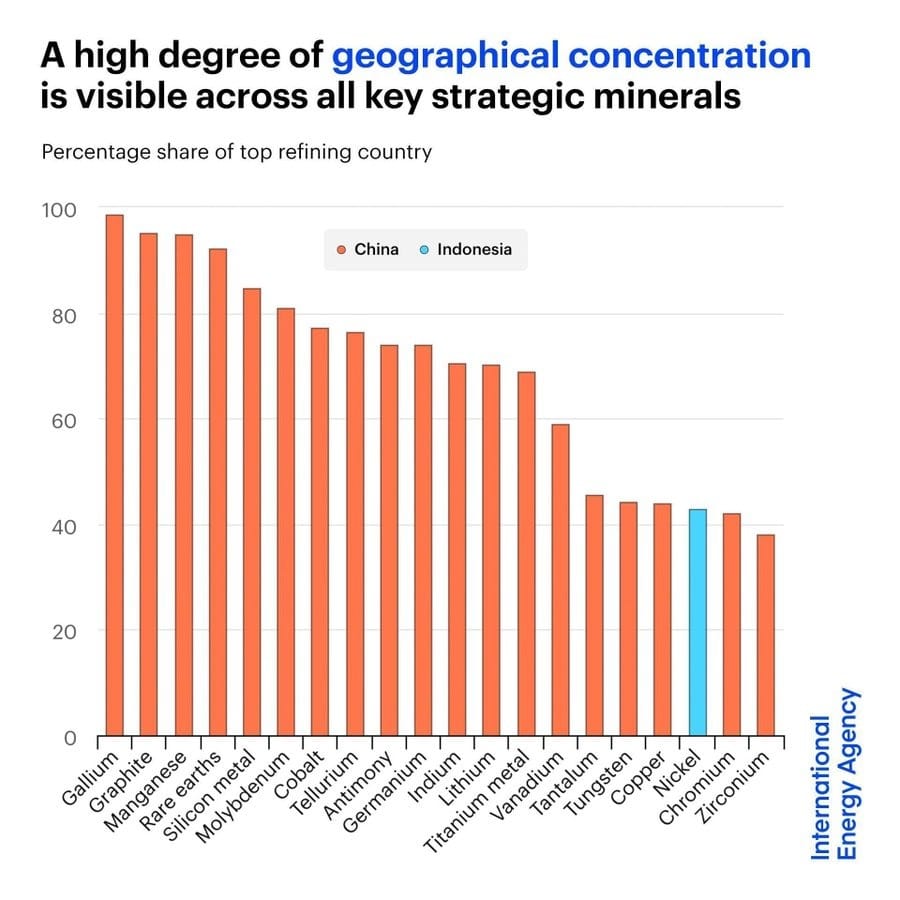

The end result was that over time, China came to control more than 90% of global refining capacity for graphite and rare earth elements and now processes roughly 60% of the world’s lithium and cobalt.

And the world got a taste of how hard it would be to break this dominance last year, when China began imposing export controls on rare earths and other critical minerals. Some of it was because it didn’t want its technology to be used in defence sectors of other countries, while the rest was a retaliation against tariffs the US had slapped on Chinese goods.

The impact as you would imagine was no surprise. Supplies tightened and countries were suddenly scrambling to find alternative sources of minerals they had quietly taken for granted.

Now, it’s worth noting that even though the US and China later agreed to a one-year truce where China would suspend export restrictions, and the US would ease tariffs, it was clear that being this dependent on one or two countries for materials that sit at the heart of modern tech is a serious risk.

So now the US thinks it has a plan.

Instead of doing it alone, it wants to bring friendly countries that mine, process, or rely on the same building blocks of technology and AI, on the same page, through a new alliance called Pax Silica.

What’s that, you ask?

At its core, the name is pretty literal. Pax is Latin for “peace”, and silica is a key compound used in chip manufacturing. Put the two together, and Pax Silica is about keeping the peace in the tech world by controlling the stuff that powers it.

So, instead of every country trying to lock down critical minerals and supply chains on its own, Pax Silica is meant to be a trusted club of allies that coordinate with one another. The idea is simple. Countries share access, plan supply chains together, and reduce dependence on China by treating things like silicon chips, rare minerals, data centres and electricity as strategic assets. Much like oil or military alliances were treated in earlier eras.

Right now, countries like Australia, Greece, Israel, Japan, Qatar, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, the UAE and the UK are officially part of the alliance. Others like Taiwan and the EU, are still keeping some distance, maintaining their own policies or reservations about formally joining.

And now India could be next.

Last month, the US officially invited India to join Pax Silica. And the reason why this is important is that India has already started positioning itself as an alternative manufacturing hub under the “China plus one” strategy. And while its AI infrastructure and scale are still very, very nascent, this could be a chance to plug into fresh investments and deeper partnerships under the initiative.

It also helps that many of the original members of Pax Silica already sit near the top of the AI and semiconductor supply chain. In that sense, it’s a give-and-take arrangement. One country brings strength in one strategic area, another fills a different gap, and both walk away better off.

You can already see hints of this materialising. For example, Microsoft recently announced plans to spend $17.5 billion expanding its AI infrastructure and cloud computing capacity in India over the next four years. Google followed up with plans to invest over $15 billion across five years to set up an AI data centre in Andhra Pradesh.

India, for its part, brings something valuable to the table too. It has the world’s third-largest reserves of rare earths, growing manufacturing capabilities, and a massive workforce. Together, that makes it a viable alternative supply chain, even if it’s still early days.

Which brings us to the real question: Can Pax Silica actually break China’s dominance in critical minerals?

Well, to answer that we have to go back to the story on how China came to dominate the global critical-minerals mining and refining space. What we told you earlier was only half the story. The other half is how it did it.

See, China didn’t take control by owning everything outright or by announcing grand strategies. Instead, it moved quietly by building what is effectively a “silent cartel” of companies and opaque contracts.

For context, between 2000 and 2021, Chinese banks issued about $57 billion in mining and processing loans across 19 countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia and Kazakhstan. Using this money China began to control the flow of minerals in these countries through shell companies, offshore registrations and minority stakes. On the surface, it must have looked like these countries had control on their mineral resources. But underneath, Chinese-linked firms secured effective control over cobalt, copper, tin and chromite without openly owning the assets.

Many of these deals also include private contracts that guarantee Chinese buyers first access to mineral exports through Right of First Refusal (ROFR) agreements. In simple terms, China gets first dibs, often at market or even below-market prices, before anyone else can bid. And because these agreements aren’t public, Western companies often don’t realise that the supply is already spoken for.

What’s even more important to understand is that mining is only half the battle. Most minerals still need to be refined before they can be used in batteries, electronics or weapons systems. And this is where China’s grip tightens further. It dominates the refining stage, processing the majority of the world’s critical minerals. And that gives it the power to decide who gets access, when supplies slow down, and which industries feel the pressure first.

This is why it’s so hard to simply out-mine, out-process or out-fund China, even if alliances like Pax Silica manage to bring countries together. Because for years, the rest of the world let China do the dirty, polluting work while enjoying the cheap inputs that came with it.

So yeah, the one realistic way forward now lies in secondary sources such as recovering minerals from mine waste, using new technologies to extract rare earths from tailings, coal ash and industrial by-products, or even tapping wastewater from oil and gas extraction. Recycling old electronics and e-waste will also have to play a much bigger role.

But that also raises another uncomfortable question: Who takes on this burden?

Emerging economies like India or countries that want to contribute more to global GDP, play a bigger role in strategic alliances, and attract fresh investment.

China eventually cleaned up its pollution mess by shutting down illegal mines, containing water bodies contaminated by critical-mineral mining, and consolidating the industry under state control. But are countries like India thinking just as hard about the after plan, about how to deal with the pollution that comes bundled with this opportunity?

That’s something no one really knows.

Or maybe, deep down, we do.

Until next time…

Liked this story? Why not share it with a friend, family member or even a curious stranger on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and X?

How Strong Is Your Financial Plan?

You’ve likely ticked off mutual funds, savings, and maybe even a side hustle. But if Life Insurance isn’t a part of it, your financial pyramid isn’t as secure as you think.

Life insurance is the crucial base that holds all your wealth together. It ensures that your family stays financially protected when something unpredictable happens.

If you’re unsure where to begin, Ditto’s IRDAI-Certified insurance advisors can help. Book a FREE 30-minute consultation and get honest, unbiased advice. No spam, no pressure.